The Memory of the Last Chaplain to Die in World War II Remains Alive

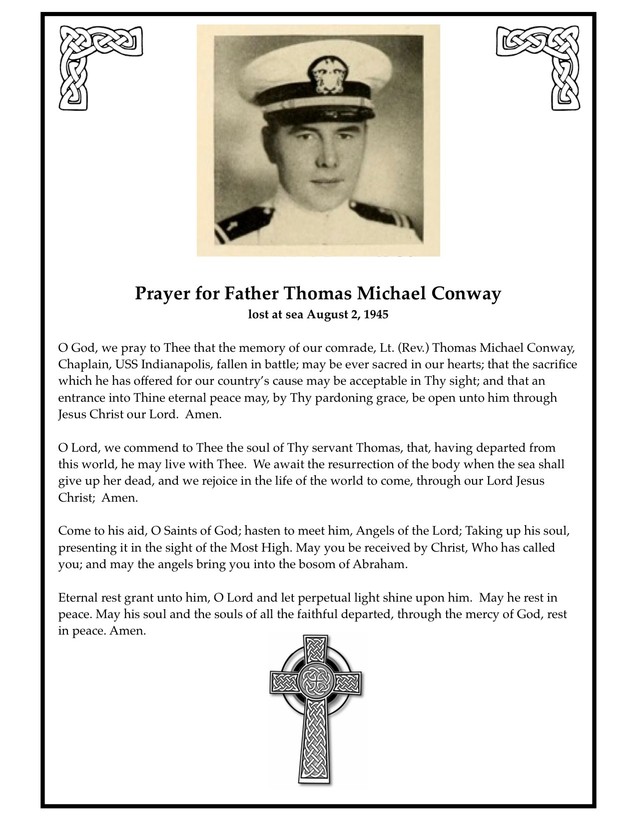

Father Thomas Conway gave his life for his naval flock.

As the USS Indianapolis headed through the Philippine Sea, at approximately 12:14am July 30, 1945, she was hit by two torpedoes from a Japanese submarine. The first took off her bow; the second blasted amidships. The disaster has become the Navy’s worst-ever loss of life at sea — a tragedy of horrific proportions. The Indianapolis went under in 12 chaotic minutes.

More than 300 of the 1,195 sailors and Marines on board went down with the ship.

A month before the official ending of World War II, Father Thomas Conway became the last Catholic chaplain — the last chaplain of any denomination — to give his life for his flock during the war. The chaplain was one of the initial 880 survivors who would face several days at sea under horrendous conditions. He died with the those in the water after the ship was hit.

But from the moment the ship started to sink, Father Conway’s actions were the stuff that distinguishes real heroes.

Determined Chaplain

That fateful July day chaotic conditions saw men scattered over the open ocean. Everyone didn’t have a chance to get a kapok life jacket. Many were injured and covered in the ship’s fuel oil. Soon they would face attacks by sharks. And the Navy would not know for days of the ship’s disappearance.

“Father Conway served as their spiritual mentor and their supervisor for three and a half days,” said Robert Dorr, secretary of the Waterbury Veterans Memorial Committee in Waterbury, Connecticut.

In the last several years the committee has tried to have this brave chaplain, a native of the city, awarded the Navy Cross posthumously.

“He was in water with 400 survivors on a floating cargo net,” Dorr said. “As they were dying, he gave the last rites, or baptized them or gave them absolution.”

With Father Conway was Capt. Lewis Haynes, the medical doctor aboard. In a personal remembrance of the ordeal printed in The Saturday Evening Post in 1955, Haynes paid tribute to Father Conway, saying that “we have found one comfort — a strong belief to which we cling. God seems very close. Much of our feeling is strengthened by the chaplain, who moves from one group to another to pray with the men. The chaplain, a priest, is not a strong man physically, yet his courage and goodness seemed to have no limit.”

Limitless they were. For more than three days, he and Haynes swam among the approximately 400 survivors around them. Clinging to the cargo net, they suffered increasingly from lack of food and drinking water, as well as the blazing sun on the open ocean.

But ceaselessly Father Conway swam to each individual group, helping the wounded, organizing prayer groups, bolstering spirits, ministering to the dying and giving last rites, swimming after those who were weak and letting go of the rope to haul them back, holding up those who were drowning, and encouraging the men not to give up hope.

He comforted them, “You will either be going home or you will be with the Lord.”

Frank Centazzo, one of the survivors cited in different remembrances, recalled: “Father Conway was in every way a messenger of Our Lord. He loved his work. … He was respected and loved by all his shipmates. I was in the group with Father Conway. … I saw him go from one small group to another, getting the shipmates to join in prayer and asking them not to give up hope of being rescued. He kept working until he was exhausted. I remember on the third day, late in the afternoon, when he approached me and Paul McGiness. He was thrashing the water, and Paul and I held him so he could rest a few hours. … Father Conway was successful in his mission to provide spiritual strength to all of us. He made us believe that we would be rescued.”

Years later, survivor Donald McCall would share how “Father Conway led us in prayer when we were in the water and told us we’d be safe, that help was coming.”

That was typical of the way the chaplain had always aided the Indianapolis men.

On Aug. 25, 1944, he was aboard the heavy cruiser, which had just completed a secret mission delivering parts of the first atomic bomb to the airbase on Tinian. As the flagship of the 5th Fleet, the ship’s crew had earned 10 battle stars. Before its last fateful mission, the Indianapolis had undergone major repairs in California after being seriously damaged at Okinawa that March during a kamikaze attack. Nine sailors had died, and Father Conway did their burial service.

While the ship was being repaired, this chaplain, at his own expense, traveled to each of the nine families of those sailors to offer his sympathy and tell them in person about their boys.

Looking out for his men in all of their needs — physical and spiritual — was his primary concern in his last days.

Survivor Richard Thelen would share with Dorr, “On Monday morning, Father Conway swam to my group and asked if there were any Catholics there, and, of course, I was, and he said swim over this way, and we did. … He gave me the last sacraments of the Church, and then he swam away, continuing his work.”

Centazzo would add, “He gave us hope and the will to endure. His work was exhausting, and he finally succumbed in the evening of the third day.”

After three and a half days ministering to his flock, completely exhausted, 37-year-old Father Conway drowned Aug. 2. “He will be remembered by all of the survivors for all of his work while on board the Indy, and especially three days in the ocean,” Centazzo said.

Rescue did come, Aug. 5. But by then only 317 of the 880 sailors able to leave the ship had survived. The others died of their wounds, exhaustion, drinking the salt water and becoming delirious and drowning, or from attacks by sharks.

Memory Remains Strong

The Navy Cross is the second-highest decoration awarded by the U.S. military. Regretfully, Father Conway will not be able to receive one posthumously despite the Waterbury Veterans’ longtime efforts. Dorr explained that, according to Navy regulations, a recommendation for a medal has to be signed by a person or officer a grade level above in rank. Most all of the officers died with the ship, and for the formal application done in recent years, only a few survivors were still alive, none above the heroic chaplain’s rank of lieutenant. Still, Father Conway continues to be remembered and honored, especially in his hometown, where he was born to Irish immigrant parents on April 5, 1905, in the same parish as Servant of God Father Michael McGivney, the founder of the Knights of Columbus.

Both priests were baptized, received their sacraments and grew up in the same church, now the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, said Father Christopher Ford, the rector. While the edifice dates to after Father Conway’s childhood, the baptismal font is from the original church. “Father Conway was baptized in that font,” Father Ford said, adding that he graduated from the parish’s 130-year-old school.

“It’s a great source of pride because of his heroic virtues, not only during those three days, but also for what a really fine priest he was, very dedicated to the care of those souls from our country entrusted to him,” said Father Ford, who has the chaplain’s awarded medals — Gold Star Family Award; Purple Heart; American Theater Campaign Medal; Asiatic-Pacific Medal with 3 Battle Stars (Peleliu, Iwo Jima, Okinawa); World War II Victory Medal; Naval Combat Action Ribbon; Naval Distinguished Unit Ribbon. He also was awarded the City of Waterbury Service Medal (posthumously) — at the parish. “During those three days he went from one to the other, blessing and baptizing them, absolving them and comforting them. He was holding them till they passed.”

Dorr related that while interviewing survivors for the Navy Cross application, one stated, “Father Conway passed away early in the morning on Thursday, and we were spotted about an hour later. I believe it was the spirit of Father Conway that guided that pilot to our rescue.”

The Navy plane was on patrol looking for subs and flying at 10,000 feet, but for some unusual reason, the pilot decided to drop down to about 1,000 feet, where he saw the men in the ocean. Higher up, he would have missed them.

Considering only the survivors from the chaplain’s group of 400, Dorr told the Register, “We know he helped save the lives of 67 men. Only God knows how many souls he saved.”

Father Conway’s home parish annually remembers Father Conway with a memorial Mass on his birthday and with holy cards. In 2015 the Waterbury Veterans installed a memorial to him on the basilica’s grounds.

Dorr describes it as a cenotaph, “essentially an empty grave for a war hero. We decided to do this because his body was lost at sea. It depicts Father Conway in the ocean aiding a drowning sailor.” It’s purposely at tabletop height, “as if you could reach into the water and rescue the two drowning sailors,” Dorr explained.

Joan Conway of California is a niece of Father Conway. Although her uncle died before she was born, she told the Register, “I know he was very important to my father. He was kind of a father figure to my father.” She’s grateful for her uncle’s heroism and the continuing gratitude of those who were blessed to know him. “My dad would have been very touched by it.”

“He had heroic virtues worthy of his cause at least being looked into or investigated,” concluded Father Ford. “He really had qualities that would be consistent with being a Servant of God.”

Joseph Pronechen is a

Register staff writer.