The Apostle, the Jester and the Prophecy

The tale starts around the year 1123 in the reign of King Henry I...

Close by the ruins of the London Charterhouse is a place of note to the Catholic pilgrim. On the eastern edge of Smithfield, there lie St. Bartholomew’s Priory and Hospital. Although there is little that remains of the original church today, how it came to be built is a curious tale.

The tale starts around the year 1123 in the reign of King Henry I. One of the court minstrels, a ‘pleasant-witted gentleman’ named Rahere, went on pilgrimage to Rome. He had gone there after the King’s court was plunged into mourning for the death of the monarch’s son lost at sea. While in Rome the minstrel fell ill. So desperate was his plight that he vowed to build a hospital for the poor should he recover. Thereafter, it is recounted that St. Bartholomew visited him in a vision. The Apostle directed him to build the promised hospital at Smithfield in the City of London.

Rahere recovered. He returned to London but he knew as well as anyone that the area to which the vision of St. Bartholomew had pointed him was marshland, a spot there called ‘The Elms’ used only for public executions. Nevertheless, soon after, building work on the hospital commenced for the King blessed the project, as did the Bishop of London. Returning to his former profession as a minstrel, Rahere also contributed to the building as, with his music and songs, he recruited bands of children and local servants to help collect the stones for the hospital’s construction. Alongside the hospital, a priory was built. In due course, the Priory of the Augustinian Canons was established there, with Rahere as its first Prior.

Some pointed out that all of this had been foretold a century earlier. It was said that King Edward the Confessor had had a dream that Smithfield was the chosen place where one day a place of worship would be erected. It is said that Edward, waking from his dream, traveled to the site. There, the king, who would later be canonized a saint, prophesied that this ground would one day witness to God.

There is an equally strange story from that same period involving three visitors from Greece. When the Greeks came across the wastes of Smithfield, they fell to their knees. Thereafter, they talked of a temple rising up from that very ground, one that would offer worship from the rising of the sun to its setting.

In the years that followed, the church and priory both thrived, not least because of continued Royal patronage. The excellence of the chapel design showed the importance given not just to the medical treatment available there but also to the spiritual healing offered at St. Bartholomew’s. In fact, the wards for the sick were designed with a chapel at one end so that all present could hear Holy Mass as well as listening to the Canonical Hours of the Church if they were well enough.

The hospital at St. Bartholomew’s cared chiefly for the poor. In particular, it cared for pregnant women; it even had a maternity clinic. Women were looked after throughout pregnancy, both before birth and during the delivery, recovery and churching. But a myriad of ailments were treated at St. Bartholomew’s, with the Augustinian Canons administering much of this medical care. Their then expertise as medical practitioners is not to be underestimated. In fact, one 14th century Canon, John Mirfield, wrote an important medical textbook, Breviarium Bartholomei, drawing on his experience of working at the London hospital.

The poor of London gratefully received the healings St. Bartholomew’s Hospital brought to their lives and the rich lavished gifts upon the foundation. Dick Whittington, the famous Lord Mayor of London, bestowed money upon the hospital, as did many monarchs. Each year an annual fair was held at Smithfield to raise funds for the work of the Canons; it was called Bartholomew Fair. It went on right into Victorian times, but much else besides ended with the English Reformation.

The Priory Church, patronized at its inception by a King Henry, was now vandalized on the orders of another King Henry. When the Canons were expelled, the buildings and land passed to the Crown. Soon after, Henry VIII sold them so little did he care what became of the hospital and its sick. The man who bought it from him was the new Attorney General, Sir Richard Rich. The same Rich who had betrayed Thomas More; the same Rich who could not look More in the eye when in Westminster Hall as his former master asked: ‘…for Wales?’ Henry’s work of demolition and desecration was continued apace by its new owner. It halted temporarily under Queen Mary, when what was left standing of St. Bartholomew’s was passed to the Dominican Order. Like the restoration of the faith in the country at large, however, Mary’s short reign proved only a temporary respite.

On the accession of Elizabeth I, the church was once more deconsecrated. Thereafter, a blacksmith set up his forge in the north transept where to this day the soot of the forge can still be seen upon the church walls. A garment manufacturer set up shop in the Lady Chapel; the cloisters became stables; the crypt was used as a storeroom for coal, and so on.

During the reign of ‘Good Queen Bess’ some of those who continued to adhere to the ‘Old Faith’ were martyred nearby at Smithfield. From the time of her father, criminal executions at Smithfield had been replaced by a procession of martyrs. The blood letting had started in 1538 with the Franciscan Friar, John Forest. He had been confessor to Queen Catherine of Aragon; he had also denounced both Henry’s ‘divorce’ and his claim to spiritual independence from Rome. For his witness, the friar was slowly burnt to death, hanging from a height, and while one of the King’s new churchmen, Latimer, roared abuse at the priest. But even this incident proved curious. Part of the fuel used to burn the friar to death was a giant wooden statue of St. Derfel. Many years earlier, this statue of this Welsh saint had been brought to London with a strange prophecy attached to it: one day it would set a forest on fire.

By the 18th century, the ruined church and monastery buildings, those which were left, offered shelter to the homeless — an oddly apt return to earlier times when London’s poor came for healing and alms from the Priory that once occupied that ground.

In the end, St. Bartholomew’s Hospital faired better than the church. Aware of the needs met by the hospital, merchants of the Corporation of London were granted it by Henry VIII; the hospital has continued down though the centuries treating the sick, as it still does to this day. In its way, this care of the sick continues to be a distant echo of another time when the healing of the soul and the healing of the body were considered as two parts of a greater whole.

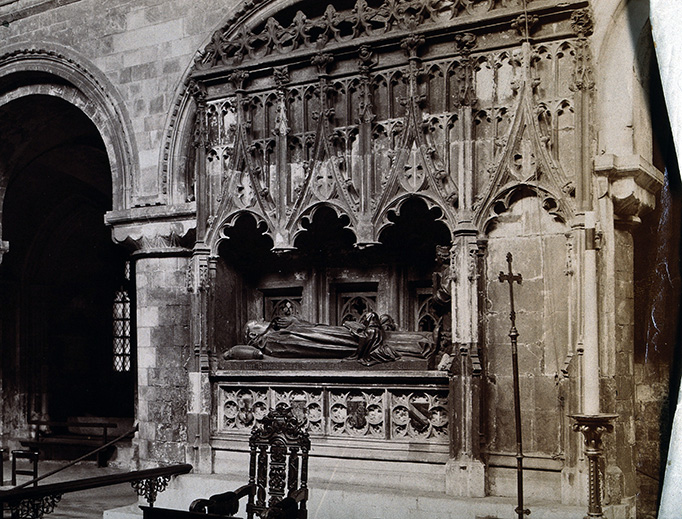

In what is left of the original structure, now part of a later refashioned Anglican church, there is the tomb of Rahere, court minstrel and first Prior of St. Bartholomew’s. Local legend claims that his spirit haunts the building. It is reputed to appear each July 1, emerging from the vestry of the new church that has been constructed on the ruins of the old. Perhaps, though, it is not a ghost, but something else tasked to remind all present that July 1 is the day dedicated to the Precious Blood. Within these hallowed grounds, and for many years a bell rang out at the Consecration as the Sacred Species was made present once more. For many centuries now, there has been only silence.

It is ironic, or more correctly apt, that today Smithfield, the site of martyrdom, is a butchers’ market. In the streets around, there appears little to suggest the fulfillment of the prophecy of Edward the Confessor, king and saint, or that of the mysterious Greeks. There is even less, however, to recall those who died there giving witness to the true faith.

And yet, maybe the prophecies referred to the new Temple foretold in the pages of Scripture. In Tudor times a sacrifice was made upon this ground. Perhaps it is that which is the continual worship prophesied, one in spirit and in truth, and one whose martyr’s blood is the seed of the Church that persists still in this city in spite of persecution, in spite of death, in spite of everything.