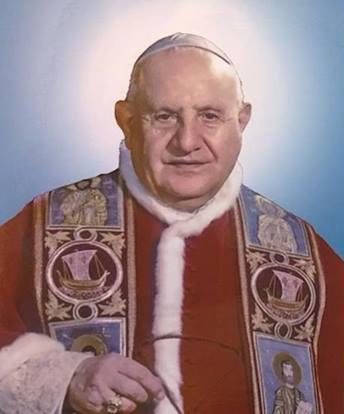

St. John XXIII’s ‘Aptitude for Goodness’

Special Section: John Paul II John XXIII: Papal Saints for the New Evangelization

The first Pope John XXIII, Baldessare Cossa (d. 1419), was initially a stormy character who became one of the Pisan "anti-popes" during the troubled Western Schism, when the political division of papal candidates seemed to produce three popes. This problem was solved when Cossa abdicated and Martin V became pope in 1415. The troubled Avignon exile of the papacy ceased with the papacy’s return to Rome.

With this unfortunate memory in mind, the first act of Angelo Roncalli, when elected pope in 1958, was to choose a name. He did not take John XXIV, but precisely John XXIII. This choice was astute. It revealed a man who knew the history of the Church and the significance of names. By himself taking the name John XXIII, Roncalli implicitly set to rest any doubt that Cossa was not a real pope.

Many stories circulate about the wit of John XXIII. My favorite is his response (apocryphal or not) to a journalist who asked him: "How many people work in the Vatican?" He is said to have replied with some amusement: "About half."

One cannot help but wonder if the same question were asked of any other bureaucratic organization in the world whether the average percentage of workers who actually worked would be much different, though talk of "reforming" the Vatican bureaucracy flourishes under Pope Francis.

I was thinking of this Roncalli response when I read the following passage from his 1961 encyclical, Mater et Magistra (Christianity and Social Progress): "Whenever temporal affairs and institutions serve to further man’s spiritual progress and advance him toward his supernatural end, it can be taken for granted that they become at the same time more capable of achieving their immediate, specific ends. Indeed, the words of our Divine Master are still true: ‘Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his justice and all these things will be given to you besides’ (Matthew 6:33)" (257).

All through the modern era, the sophisticated thesis has been argued that concern with our transcendent end did not help our temporal prosperity, but hindered it. By being so concerned with the supernatural, men neglected their worldly affairs. That is why, it was claimed, religion, the "opium of the people," is an impediment to world betterment, not a help. John XXIII made the opposite claim.

It is precisely when we have our minds and souls properly ordered to the Eternal City that we can best work, live and improve in the cities of men on earth. "The moral order, however, cannot be built except on God," Pope John explained. "Cut off, it disintegrates. Man, in fact, is not only a material organism, but also a spirit endowed with an awareness of his reasoning power and freedom" (206).

What we are witnessing after John’s time is precisely this disintegration, this denial of the validity of our "reasoning power," and an interpretation of freedom that has no natural limit or order.

L’Osservatore Romano (English) on March 7, 2014, reprinted the column from the New York Herald for June 7, 1963, by the famous American journalist Walter Lippmann on the occasion of Pope John XXIII’s death. "We know that the miracle of Pope John will not transform the world," Lippmann wrote. "The condition of man is a hard one, and his struggle to survive and to prevail will not disappear with the appearance of a saint and the proclamation of saving truth. We shall not suddenly become new men. But the universal response which Pope John evoked is witness to the truth that there is in the human person, however prone to evil, an aptitude for goodness."

This is a perceptive and well-chosen phrase — "aptitude for goodness" — to explain a power in the world that is a gift and comes unexpectedly among us, even, rather often in recent years it seems, from the papacy itself.

Truth is something we can choose to ignore. We have more difficulty ignoring sheer goodness.

Pope John published privately a book of some 727 letters written over the years to his family. It is a touching sidelight to the pope’s character. In his spiritual autobiography, Journal of a Soul, he set down six brief maxims for attaining perfection. In honor of his canonization, they are worth repeating:

1) Desire to be virtuous — and so pleasing to God.

2) Direct all things and thoughts, as well as actions, to the increase, the service and the glory of Holy Church.

3) Recognize that I have been sent here by God — and therefore remain perfectly serene about all that happens, not only as regards myself, but also with regard to the Church, continuously to work and suffer with Christ for her good.

4) Entrust myself at all times to Divine Providence.

5) Always acknowledge my own nothingness.

6) Always arrange my day in an intelligent and orderly manner.

In reading these brief sentences, we do have the impression of a serene man who knew he was in the hands of God, entrusted through the Church to his Divine Providence. One cannot help but smile at a man who "acknowledges his own nothingness," waking up every morning to figure out how to organize his day in an "intelligent and orderly manner."

A final story, as I recall, is told of Pope John. He was in full papal regalia, listening to a homily that went on and on and on. Finally, when it seemed like it would never end, he turned to a bishop next to him and whispered, rather loudly, "Coraggio" — it takes courage to patiently sit through long-winded homilies.

Pope John XXIII had an "aptitude" for history, for remembering our supernatural end, for humor, for the signs of the times — and, above all, for goodness. This is why he is a saint.

Jesuit Father James Schall retired from teaching political philosophy at Georgetown University in 2012. A prolific essayist and author, his latest book is Remembering Belloc (St. Augustine Press).

- Keywords:

- April 20-May 3, 2014