Clerical Abuse Survivor: Faith Is a ‘Powerful Tool to Heal’

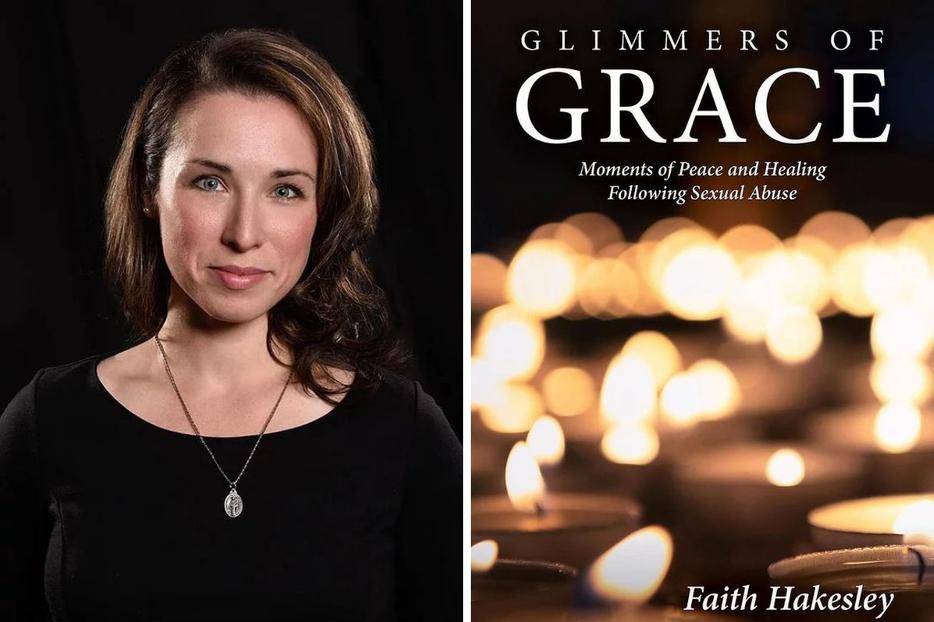

Author of ‘Glimmers of Grace: Moments of Peace and Healing Following Sexual Abuse’ speaks about her new book and about healing, why victims are often silent, and why she stayed Catholic.

Faith Hakesley was sexually abused at age 15 in 2000 while working at a part-time job as secretary at her parish church. Her rapist, the now-laicized Father Kelvin Iguabita, was sentenced to eight to 10 years in prison in 2003 and then deported back to Columbia.

In 2008, Hakesley and four other survivors of clergy sexual abuse from the Archdiocese of Boston met with Pope Benedict XVI during his visit to Washington, D.C.

The now-married mother of three, with another child due in January, spoke with the Register about her new book, Glimmers of Grace: Moments of Peace and Healing Following Sexual Abuse, and about healing, why victims are often silent, and why she stayed Catholic.

What Hakesley went through takes on greater poignancy in light of the just-released McCarrick Report, which details the perverse misdeeds of one of the most visible Church leaders in the United States in the last part of the 20th century and into the 21st.

It took several months before you left your job and almost a year before you told your parents. Why did it take so long?

I talk about grooming as a type of brainwashing in the appendix of the book for people who don’t understand sexual abuse.

I worked every Saturday for a whole summer. Whenever he saw me, he’d find a way to have contact. I quit my job in the fall and told my pastor and parents it was affecting my grades. It actually was. Then he asked me to give him violin lessons in front of my parents, so there were several other instances before he was transferred.

My parents had always told us that we could come to them with anything, but predators are good at gaining trust and desensitizing the victim. Sometimes they lead a victim to think they must have wanted this, or there are threats involved. I was a shy and socially awkward 15-year-old adjusting to high school and asked for his advice. He had become my confident; and by the time he struck, I was shocked and felt as if I must have led him on somehow.

And the parish loved him, so why would they believe me? As so often happens to victims of abuse, I lived in a deep pit of fear, shame and confusion.

How did the truth come out?

My parents had me see a grief counselor over the death of my oldest brother, Matthew. He was in his early 20s, and I was 16. I was the one who found him unconscious on the floor. He had been on the phone, and I heard him gasping for breath. He was pronounced dead a few hours later. The autopsy report showed a heart condition.

Matt died in 2001, and the abuse had happened in 2000. I was carrying the grief of both my brother’s death and the abuse. It sent me into a tailspin. In my very first session, I blurted everything out. The counselor explained during the first meeting that she was a mandated reporter. She let me know that she had to report it to the Department of Children and Families.

My counselor gave me the confidence to tell my parents. They believed me right away and never asked why I didn’t come forward earlier. It’s important for loved ones to understand how important that is. I can’t imagine people who carry that burden around and never tell anyone. Eventually, I sat down with detectives, and the Archdiocese of Boston was alerted that something was up with Kelvin Iguabita.

What was the response when it went public?

Charges were pressed in 2002, and the media covered it extensively. The Boston Globe assembled a team to investigate the allegations. Some people said I was a grief-stricken girl making up a story. Since a 15-year-old cannot make that decision with a 32-year-old man, I was not really accused of wanting to go along with it.

I went to a Catholic high school and dealt with a certain amount of bullying. I had been a quiet girl and people knew I was religious. There was some teasing: “Of all people it would be her, Faith, the virgin, the good girl.”

The case went to court right after my graduation. There were seven women who contacted me when they heard about it and said he did the same thing to them.

Why did you stay Catholic after your abuse?

I was raised in a good Catholic family with three brothers and had such a love for Catholic tradition and the saints, especially St. Thérèse, the Little Flower. Faith was ingrained in me, but because of who my abuser was and where it took place, the spiritual aspect of my life was so betrayed.

I kept my faith — even though it was small at times — through the sacraments. I could not let go of receiving Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament even when I was mad at God. I tell anyone who is a person of faith that they can use that as a powerful tool to heal.

There is pain and suffering in the world, and sometimes people fail us — not just in the Church, but in families and schools. We should hold the Church to a higher standard but still be able to recognize the human aspect of sin.

It was a man who was narcissistic and listened to the wrong side — not God — who hurt me. I was able to accept that over time, once the chaos calmed.

How did your faith help you to heal?

Healing includes mind, body and spirit. In my book, I encourage all three, or else something is going to get missed.

Turning to Jesus was not something I truly embraced until later on. During those months of abuse, I felt abandoned by God. In hindsight, I am so grateful that the Catholic faith was at the core of my family. When the abuse was going on, I was still praying, but my faith was just the size of a mustard seed. Now I see how powerful prayer and my relationship with God was.

In the midst of my suffering, there came a time when holding on to faith became a decision. I had to choose between abandoning faith or turning to the Lord, despite my doubt. I found more healing in my faith than anywhere.

What is the reason you do not talk about forgiveness in your book?

I talked about freedom instead. I didn’t want to mention the word “forgiveness.” For someone just coming to terms with their abuse, that’s the last thing they want to hear.

If Jesus could love us from the cross and love those who put him on the cross, who am I to withhold forgiveness? True freedom starts with forgiveness, but it takes a long time to get there. It’s something you have to do over and over again. Anger and resentment can pop up, so you have to make the decision again.

My parents were suffering a lot; they had just lost a son, and now they had to deal with this — but they were having Masses offered for my rapist once a month. I didn’t like it at first — that they forgave. My dad told me: “If you keep up this resentment and hatred, it will take you over.” Forgiveness gives you room for freedom.

What was it like meeting Pope Benedict XVI in 2008?

I was the youngest victim invited to meet him in Washington, D.C. It was the year I got married. I was in my early 20s, and the other four were in their 40s and up. It was three males and two females. I had met with Cardinal Seán O’Malley earlier, a few years after the trial; he had come to our home to apologize.

When I met Pope Benedict, I just cried. I asked God to give me something to say to get across the pain I had been through. When my time came, I burst into tears. As much as I was frustrated, and wanted it to stop, I realize that’s just what I needed to say. I looked up at the Pope and saw tears in his eyes. God saw fit to speak through my tears. One of the last things Pope Benedict said to me is, “There is always hope.” I hope that people will take that from the book — no matter how dark, there is always hope.

What is your hope for this book?

I wrote it for survivors of abuse and people who support them and for anyone trying to better understand the impact on victims. Visible scars may be the first to fade, but we are left with wounds in our minds and hearts. These inner wounds are what this devotional seeks to address.

I hope that this book can be a supplement for counseling. It is not meant to replace it. However, I understand, due to many different circumstances, that not everyone feels able or ready to come forward about their experiences; but I always encourage victims to come forward when they can.

I have a desire to take a piece of my healing and give it to others. It’s less about me and more about how God can help. I want people to know they are not alone, and there is life after abuse. I pray for everyone reading this book, but I pray especially for those who feel trapped in silence.