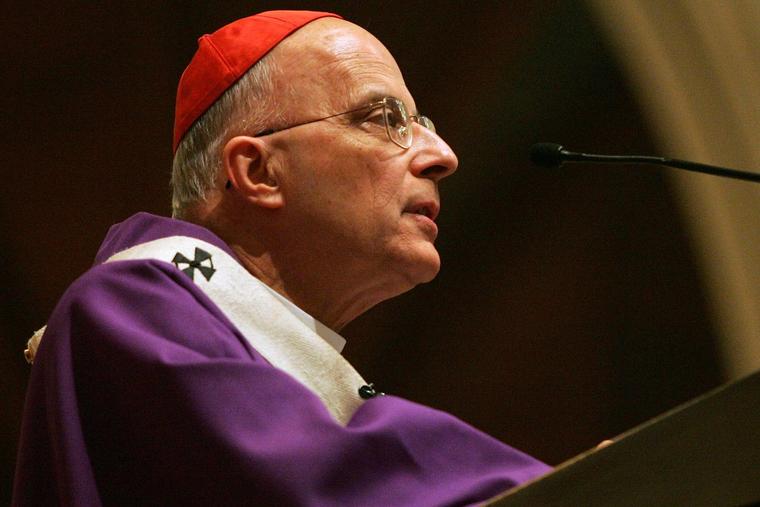

‘A Deeply Pastoral Heart’: The Legacy of Cardinal Francis George

The late Chicago archbishop, as chronicled in a new biography, made ‘the holiness of his people his top priority’ and championed ‘simply Catholicism.’

Cardinal Francis George, one of the most consequential U.S. prelates of the past century, almost failed to achieve his goal of becoming a priest. Childhood polio left him with a lifelong physical disability, and he was turned away from the Archdiocese of Chicago’s minor seminary. George persevered, however, and was accepted by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

While serving as vicar general for his worldwide order, he drew the attention of Pope St. John Paul II; and in 1990, he was made the bishop of Yakima, Washington. Before long, he would return to his hometown as the cardinal- archbishop of Chicago and was elected president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Now, in a fascinating and timely new biography, Glorifying Christ: The Life of Cardinal Francis E. George, O.M.I. (Our Sunday Visitor Press), author Michael Heinlein provides a rich, nuanced portrait of a visionary Church leader who was celebrated — and reviled — for his forthright defense of inconvenient truths, yet adamantly rejected the label of “culture warrior.”

In an email exchange with Register Senior Editor Joan Frawley Desmond, Heinlein reflects on his subject’s remarkable personal virtues and prophetic witness that still offer lessons for his brother bishops and the lay faithful as they live the Gospel in the modern world.

Psalm 118 speaks of the coming Messiah: “The stone that the builders rejected has become the chief cornerstone.” But, in a sense, this paradox also applies to Francis George, who was denied admission at Chicago’s minor seminary yet became the “best and brightest” of his generation of Church leaders. Did that intrigue you?

There are absolutely some parallels between Cardinal George’s story and Our Lord’s. He bore the cross as a man living with disability most of his life. But, as the cross was a gift and brought life, so, too, did Cardinal George come to see the polio as a gift. We can think of the suffering servant, rejected and despised.

At the beginning, his hometown rejected him — saying that, on account of his disability from polio at 13, he couldn’t be a priest in Chicago — and then when he returned home as archbishop in 1997, a vocal group of priests of Chicago rejected him again for being intent on governing according to the mind of the Church. It’s hard not to be intrigued by his story.

Childhood polio left him permanently disabled. But, early on, faith gave him hope: “I was not alone, and good can come of something that appears bad.” How did the crucible of suffering shape his legacy?

Cardinal George’s sister Margaret recently remarked in an interview that “the polio made him holy.” And that certainly is true. He was a man of perseverance and tenacity, but also of authenticity and integrity. I think living with disability, and also battling cancer for nearly the last 10 years of his life, Cardinal George could be close to those who are marginalized and poor. The news cameras weren’t usually around when he was the last person to leave a parish event or help at a soup kitchen. But he was very close to his people; he had a deeply pastoral heart. And there’s no question that his life of suffering attuned him this way.

Francis George was ordained a Missionary Oblate of Mary Immaculate. How did that charism animate his priestly vocation and episcopal ministry?

Cardinal George often spoke of how it was the Oblates who taught him how to pray and how to love the Church. So the Oblate spirituality was itself definitely very much part of his own pursuit of holiness in the vocation as priest and bishop. Their mission is to preach the Gospel to the poor, and this was at the heart of all his ministry and also in his own response to the call to discipleship. I’d also add that the founder of the Oblates, St. Eugene de Mazenod, was also a diocesan bishop.

While much of Cardinal George’s life was focused on St. Eugene’s role as founder of the Oblate charism, he later turned anew to his writings for counsel after he was himself named a bishop. St. Eugene founded the Oblates in the wake of the French Revolution, and his experiences and ministry reflected the great tension between Church and state at the time. Cardinal George was able to draw on this knowledge when he led the U.S. bishops, as USCCB president from 2007-2010, through challenges of religious freedom, particularly the HHS mandate of the Obama administration.

He also dismissed “liberal Catholicism” as an “exhausted project” that “no longer gives life.” What prompted this critique, and how would he distinguish his own interpretation of the Second Vatican Council as he advanced to the highest levels of the Church?

Cardinal George explained that these remarks originated, at the time he was named a cardinal in 1998, in his own reflections on a similar argument made by St. John Henry Newman from the time he was himself named a cardinal. More than a critique, though, Cardinal George advocated for “simply Catholicism,” which was itself a reformulation of the reforms and renewal began by the Second Vatican Council. He wanted the Church to transcend the ideologies, agendas and polarizations that crept in after the Council. He worked hard to foster unity and communion in the life of the Church.

Some prelates now contend that Church discipline governing reception of the Eucharist gives too much weight to sexual sin and turns off young Catholics. How did he approach the role of Christian sexual ethics in Church discipline? Was he able to make Church teaching appealing to the young?

When Cardinal George was named to Chicago, he remarked in a press conference, “The bishop is a symbol of unity; he’s to be a point of reference. The faith isn’t liberal or conservative,” he said. “The faith is true, and I will preach the faith.” That he did.

This answer illustrates his approach to any of the Church’s teachings. He was concerned about fostering unity by proclaiming the truth — not imposing but proposing it, as John Paul II liked to say. “Christ did not die on the cross and rise from the dead so that we could believe whatever we like and do whatever we please,” he once said.

Cardinal George focused on ensuring that the faith was taught with integrity with a focus on formation of those who form others. So this meant he was particularly attentive to the seminary formation in the archdiocese; the formation of permanent deacons and lay ecclesial ministers, too. He was a great supporter of a chastity awareness program in the archdiocese. He was a convincing and nuanced speaker, which made him one of the more popular American bishops at World Youth Day catechesis sessions during his time in office.

In Yakima, he warned that the vow of celibacy, when “half-heartedly accepted, can create a void” that may be filled with a priest’s “own compulsions.” What did he mean?

The Catechism of the Catholic Church speaks of how priests are called from among those called to celibacy. Of course, this is often different in practice, where celibacy is looked upon less as a good and more as a sacrifice.

I think Cardinal George was speaking here about the realities of how when celibacy isn’t fully embraced, and a priest’s life is less than fulfilled, he will turn to other things to find the fulfillment for which he's looking. As archbishop of Chicago, he also asked any of his own priests who were living a double life to leave the priesthood for the good of the Church.

How does that concern compare with the position of Church reformers in Germany, who view celibacy and episcopal cover-ups as root causes of their abuse crisis?

I don’t think that Cardinal George would blame celibacy for the abuse crisis, except to the extent that priesthood was embraced by some who did not embrace chaste celibacy. I know he loathed episcopal cover-ups of abuse.

During the 2002 abuse crisis, he helped secure the “zero-tolerance” policy for clergy facing “credible” allegations of abusing minors, a stance widely supported but now facing pushback. Did he ever question that reform, or explain why he didn’t fight to hold bishops to the same standard?

Cardinal George was initially unsure about zero tolerance with abusive clergy. He was persuaded at first by laity he consulted on the issue; and later in talking with bishops, he was of the mind it was something necessary in order for bishops to be able to govern amid the unfolding crisis.

He had, in fact, warned the Holy See that bishops would begin resigning without the provision. He was on record before the 2002 Dallas meeting saying that bishops ought also to be included in any provisions that the bishops adopted, but we know that did not happen. So I certainly can’t say he didn’t fight for holding bishops to the same standard as priests in this case. Given what he said pre-Dallas, I’d guess he did, but the majority apparently did not agree.

Given the scope and complexity of his tenure in Chicago, were the Archdiocese of Chicago and Cardinal Blase Cupich able to assist you with your work?

I am grateful to have been permitted to consult some materials in the Chicago archdiocesan archives during the research phase of the project. Many of Cardinal George’s family, brother Oblates, friends, former close collaborators and senior staff members, and bishops who served during his time as archbishop spoke to me extensively.

Cardinal George is less well known for his work on social-justice issues, but you cite his remarks about “white privilege” long before this term entered common usage. What principles and priorities link his tenure as vicar general of the Oblates with his subsequent ministry in Yakima, Portland and Chicago?

Social justice isn’t necessarily a term that Cardinal George would have used, but he would have been keener to emphasize the Gospel call to serve the poor, marginalized and vulnerable.

One of the issues that he began to confront head-on in Chicago was the sin of racism, on which he wrote one of his two pastoral letters during his Chicago tenure. He remains one of the few American bishops who spoke of systemic racism in our country and even in the Church. The global perspective he gained, traveling to dozens of countries during his tenure as vicar general of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, helped him to gain a unique perspective and attuned him more closely to such realities.

He was a missionary priest who became the worldwide vicar general of his order. Then this episcopal ministry was capped with his appointment as cardinal-archbishop of Chicago, with his brother bishops electing him USCCB president during that period. What made him such a deeply consequential figure in the Church?

His ministry modeled a robust, balanced implementation of the reforms of Vatican II, he brought clarity and unity to the workings of the episcopal conference in trying times, and possessed a rare combination of intellectual vigor and pastoral zeal. He worked hard to bring unity to the Church amid divisions, bring reform amid scandal, and always make the holiness of his people his top priority. And all of this was built on the foundation of a man who suffered a great deal and was an obviously authentic disciple of Jesus Christ.

- Keywords:

- cardinal francis george

- michael heinlein

- our sunday visitor

- archdiocese of chicago

- pastoral care

- simply catholicism