The Blood of St. Oliver Plunkett is the Seed of the Church in Ireland

ANALYSIS: Irish Catholics will increasingly need the courage, wisdom and perseverance of martyrs like St. Oliver Plunkett to spread the faith in a society hostile to the Gospel.

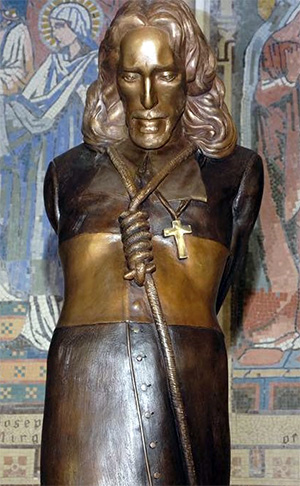

This July 10 marks the first anniversary of the unveiling of a new seven-foot-tall bronze statue of renowned Irish saint and martyr St. Oliver Plunkett, in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Armagh, Ireland. The striking statue, depicting the moment of St. Oliver’s horrific death on July 1, 1681, at Tyburn, was specially commissioned by the current Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland, Archbishop Eamon Martin. St. Oliver Plunkett was himself Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland for almost 10 years before his martyrdom.

Catholics in 17th-century Ireland suffered great persecution under English rule. The Catholic faithful, united under the pope, were viewed as a serious political threat to the English crown. Repeated attempts were made to eradicate Catholicism, and the Church in Ireland was in disarray. It was the time of harsh penal laws, when public worship and Catholic education was forbidden and priests were hunted down, imprisoned and killed. The faithful risked their lives to attend Mass in secret locations, including at open-air “Mass rocks” throughout Ireland, many of which stand to this day.

But the Irish people kept the faith in great numbers and young men desiring ordination to the priesthood were plentiful. St. Oliver like other young men following their vocation, was smuggled out of the country to study for the priesthood in Rome. Following a three month perilous journey he arrived in Rome in 1647 and spent twenty- two years in Rome as a student, priest and professor of theology. In 1669 Oliver was appointed by pope Clement IX to be Archbishop of Armagh and primate of all -Ireland. Once consecrated, he immediately left his safe and comfortable life to return to Ireland to take up this new appointment, knowing well the danger and hardship of the life to which he was returning.

During his years as Archbishop, he was an effective leader, peacemaker and diplomat, who worked hard to build bridges with the ruling authorities and made important gains for religious freedom and Catholic education. This involved the establishment of Catholic schools and reform of the education and formation of priests and religious. His efforts to rebuild the Church and renew the clergy were incredibly fruitful but also gained him dangerous enemies both inside and outside the Church. He endured hunger, poverty and suffering, with much of his time spent “on the run” from the Church’s enemies.

In the end, like the Christ he served, he was falsely accused and betrayed by his own people — in his case, Irish lay Catholics and disgruntled clergy whom he had previously excommunicated. Like Christ, he publicly forgave his false accusers and executioners before his gruesome death by hanging, drawing and quartering. As he was hung and his body mutilated and burnt, eyewitnesses described his demeanor as dignified, humble and heroic. He went to his death praying that Catholics in Ireland would persevere in their faith and good works.

The last official Catholic martyr in England, Archbishop Plunkett was beatified by Pope Benedict XV in 1920 and canonized by Pope St. Paul VI in 1975.

At the unveiling of the new statue in Armagh cathedral last year, Archbishop Martin highlighted St. Oliver Plunkett’s relevance in the face of increasing Christian persecution today. “My hope is when people feel their faith is being tested or growing weak they will visit St. Oliver’s shrine here in the cathedral and find strength and healing,” he said.

Unlike Christians in other parts of our world, Irish Catholics are not currently suffering violent persecution and death for their faith. Yet in the rising anti-Christian climate, the Irish faithful have much to learn from the courageous witness of the country’s great martyrs and saints like St. Oliver Plunkett, as embodied in this statue.

In Ireland, like most of the highly secularized West, both faith and reason have been driven further and further from the public square with destructive anti-life laws and amoral ideologies. A startling example is the extreme abortion legislation that was imposed upon Northern Ireland last month by the U.K. Parliament. Catholic clergy and laity will increasingly need the courage, wisdom and perseverance of these great Irish saints to speak out with truth and clarity against the popular tide. Perhaps the faithful will not be called to physical martyrdom like St. Oliver Plunkett, but may well suffer the martyrdom of false accusation, loss of public esteem and even damage to career and friendships.

In contemplating this impressive statue of St. Oliver Plunkett, with rosary in hand stepping serenely toward his public torture and death, we can be encouraged and strengthened by this incredible witness for Christ. We can also remember to pray and give thanks for the wisdom and leadership of St. Oliver’s successor, Archbishop Martin, for providing the faithful with this powerful and timely visual reminder of this great Irish saint and martyr for generations to come.

St. Oliver Plunkett, pray for us!

Tracey Harkin is a member of EWTN Ireland.

- Keywords:

- ireland

- martyrdom

- st. oliver plunkett