‘Son, Give Me Thy Heart’ — the Extraordinary Life of an Irish-Catholic Priest

Father Seamus O’Kielty passed away as Christendom College’s assistant chaplain, revealing a legacy of faithfully following Jesus Christ in the spirit of old Ireland’s Catholic missionaries.

FRONT ROYAL, Va. — In a simple stained-glass window standing directly over the high altar in Christendom College’s Christ the King Chapel, Jesus Christ points to his sacred heart. Beneath Christ’s feet lays an inscription: “Son, Give Me Thy Heart.”

For the hundreds of mourners that had gathered Feb. 25 to bid farewell to Father Seamus Padraig O’Kielty (1930-2019), how Jesus’ followers must answer that invitation fully manifested itself in the life of this beloved Irish-Catholic priest and college chaplain.

Since 2002, Father O’Kielty had been part of the community of Christendom College, a Catholic liberal arts community located in the Shenandoah Valley of northern Virginia. The Irish priest said in his first homily as chaplain that he wanted to finish the remainder of his priestly days among them, knowing that the Christendom community would pray for his soul upon his passing. He finally went to his reward on Feb. 18, after a battle with sepsis.

“The Catholic faith was deep in his bones,” Timothy O’Donnell, Christendom College’s president, said in his eulogy, underscoring a truly remarkable and extraordinary life of a man who had been to them a “spiritual father and grandfather” and was characterized by Irish wit and wisdom. “Who can forget his opening-semester homily, when we were told, ‘Seamus is James in Irish, and Kielty is Bondsman. So I … am James Bond.’”

Father O’Kielty had been widely known and loved as Christendom’s chaplain. He was known for calling the young men nicknames like “Billy” and the young women “Sheila,” even though he knew their names and who they were. The priest had a roguish Irish form of humor for people he cared for deeply: heaping over-the-top praise on women, mock derision on men, and telling every crew of altar servers for Mass that he had been stuck with “the bottom of the barrel.”

Because he had been ordained in 1954, the year before Pius XII started making changes to the Roman liturgy, Father O’Kielty would tease the younger priests by joking that he was the last validly ordained priest and their ordinations were suspect.

But the priest was well loved for his renowned pastoral care on campus. Multiple persons the Register spoke with recalled his absolute kindness and gentleness in the confessional, reminding them in a raspy, alliterative Irish lilt that no matter their sins, above all, Jesus loved them. Jesus’ love for them, and his desire for them to be happy and holy, was a theme of the priest’s homilies. During his time at Christendom, Father O’Kielty had inspired a number of young men to pursue a vocation to the priesthood.

“He prayed the Mass with a particular intensity of faith,” Father Frederick Gruber, a priest of the Diocese of Pittsburgh who concelebrated the funeral Mass, told the Register. Father O’Kielty’s attention to the vesting prayers made a deep impression on him. “You could feel it in how he spoke, his compassionate demeanor, his care for doing things right.”

Father Gruber said that when he was an undergraduate, at one of the college daily Masses where he was the lector, Father O’Kielty took him to task for reciting the Gospel Alleluia.

“If you don’t sing the Alleluia, you don’t say the Alleluia!” Father Gruber recalled the Irish priest telling him, driving home that the Alleluia was a cry of joy for the Christian, and so must always be sung.

To the Margins and Back

What most people who gathered to mourn and pray for the beloved chaplain did not know until his passing was the extent to which his intensity to follow Jesus, even unto the dangerous margins of the world, had defined his life.

Father O’Kielty was born on June 9, the feast of St. Columkille, on Achill Island in the west of Ireland as the eighth child in a family of 10, as the youngest boy and surrounded by five sisters. He went to minor seminary in Scotland at 12, becoming a priest at 24 years old, starting his priesthood with the Missionaries of Africa and ending as a diocesan priest incardinated in the Diocese of Paterson, New Jersey. Besides knowing at least a half-dozen languages, and being an avid pursuer of education, who was twice interrupted in the pursuit of a Ph.D. in philosophy, Father O’Kielty spent his prime years of priesthood in missions and military chaplaincies before spending his final 17 years at Christendom College.

According to information provided by Christendom College, as one of the last “White Father” missionaries from Ireland, Father O’Kielty spent 11 years in Burundi and Tanzania, until 1965, as a missionary priest. He would return to Burundi for three more years in 1974, taking over parishes once staffed by his fellow Catholic priests, who were Hutu and had been slaughtered two years prior in an ethnic-cleansing campaign orchestrated by the Tutsi government.

Between his missionary activity in Africa, Father O’Kielty went to Bolivia during the Che Guevara insurgency and served as an army chaplain. Despite the prohibitions of the Bolivian army, Father O’Kielty established a catechetical program for the indigenous Aymara people, training 100 Aymara catechists.

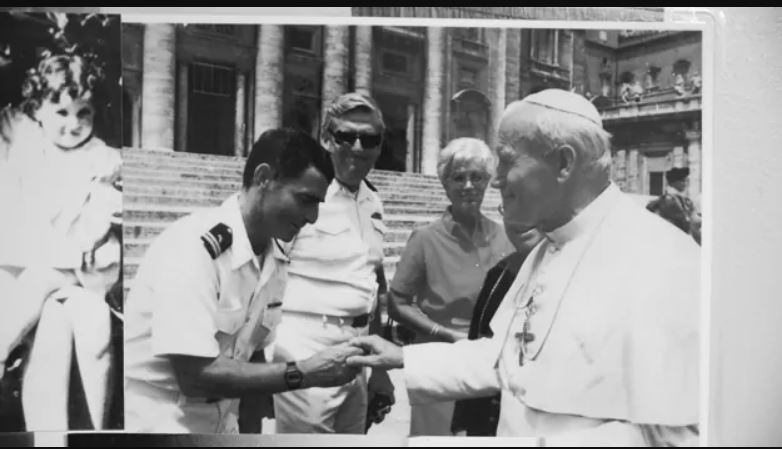

Later, he became a Navy chaplain to minister to U.S. Marines, training in jungle warfare and marksmanship so he could accompany the men in any conditions.

“Even the Protestant guys would go to him for confession” before a dangerous mission, Michelene Krebs, a close friend since 2004, told the Register (canon law allows priests to hear the confessions of non-Catholic Christians in cases of “grave necessity” or “danger of death”). Father Gruber said likewise that priests he met in the military chaplaincy knew immediately the name of Father O’Kielty and regarded him as a “legend.” Krebs said the priest, however, was a deeply private person — in a way that was typical of old Irish and Irish-American culture — and even when he opened up to close friends about his previous experiences, he would speak about them in generalities.

The Old School

The old Irish-Catholic soul permeated Father O’Kielty’s spirituality and ministry to the end.

Krebs said Father O’Kielty loved the Psalms, Mozart, Gaelic football and the Divine Office. When Father O’Kielty was driven to appointments — trouble with his vision prevented him from driving himself — he would often pray the Rosary, “and always in several languages,” Krebs remarked.

Father O’Kielty also would always resolutely pray the Divine Office in Latin. In the funeral homily, Christendom chaplain Father Marcus Pollard told the assembly that, out of concern for Father O’Kielty, who was in enormous pain dying from a septic infection, he obtained a dispensation from the bishop to say the office. He got a withering look of rebuke instead — to not pray the office was just unthinkable for Father O’Kielty. So they all prayed the Divine Office for him when the priest could no longer speak as death approached.

Other Old Irish textures showed themselves through Father O’Kielty’s ministry. He gave blessings in Irish on St. Patrick’s Day and offered the Mass in Irish. He sang Irish songs, and hearing some of them would bring tears to his eyes, along with memories of home. At the wake the evening before the funeral, one mourner recalled with amusement that the priest probably would have something to say about having a bar at his funeral remembrances. Father O’Kielty was a member of the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association, and part of his ministry at college would be inviting students to take “the Pledge” of temporary or lifelong abstinence from alcohol.

Krebs revealed that Father O’Kielty deeply felt the pain of separation from Ireland — he was born in the Gaeltacht (the Irish-speaking region) of Mayo. He loved his language and prayed his well-worn devotional books in Irish. But he had never really been able to return permanently to Ireland and carry out his priestly ministry among the Irish after his missionary activity. According to Krebs, the Irish bishops would allow Irish priests to come home from the U.S. to retire, but would not give them pastoral assignments. Krebs said Father O’Kielty spent three months at the Shrine of Our Lady of Knock, but with little to do, he returned to the U.S. ministering at parishes in the Diocese of Paterson until his arrival at Christendom in 2002.

For the sake of the priestly call, Father O’Kielty sacrificed living out the remainder of his days speaking Irish and living among his native people in Ireland — that is, until the very end. Krebs said that a hospital nurse at Warren County hospital in Front Royal met Father O’Kielty in the elevator, and they spoke in “fluent Irish” together on the way to the room where the priest would soon pass away.

“Where are you ever going to find a person from Dublin who speaks Irish at a hospital in Front Royal of all places?” she said. “It was as if God was saying, ‘Here is your language before you go home.’”

‘I Want to See Jesus’

In his eulogy, President O’Donnell said that in his final days of illness in the hospital, Father O’Kielty said he needed a raise — a running joke between the two. O’Donnell said, “If I give you a raise, will you stay?”

At that point, Father O’Kielty replied, “I want to see Jesus, not you O’Donnell!”

Krebs and others the Register spoke with said they remember him most fondly in how intensely he looked at Jesus when he spoke the words of institution at the consecration. And each time, he would breathlessly utter the traditional Irish words of welcome to the friend who crosses the threshold of their home: “Céad míle fáilte.” With Father O’Kiellty’s passing from this life, those who knew him pray that the Risen Lord, who held his priestly heart, speaks these words of greeting in return.

“Céad míle fáilte — a hundred thousand welcomes.”

Peter Jesserer Smith is a Register staff writer and a member of Christendom College’s Class of 2009.

- Keywords:

- christendom college

- college chaplains

- father seamus o’kielty

- irish priests

- peter jesserer smith