SDG Reviews ‘Pope Francis: A Man of His Word’

Veteran filmmaker Wim Wenders’ documentary sets out to connect the dots from one of the Church’s most beloved saints to the current pope.

Pope Francis: A Man of His Word opens with a God’s-eye view on a city that is neither Rome nor Buenos Aires. It is Assisi, where a visionary named Francis challenged all of Christendom with his radical reappropriation of the Gospel: his joyful celebration of the evangelical counsels, his enthusiastic embrace of poverty and of the poor and outcast, his celebration of the natural world, and his peacemaking efforts between Christians and Muslims, including his famed visit to the Sultan al-Kamil.

Wim Wenders, whose eclectic career has embraced arthouse dramas, documentaries, music videos and concert films, approaches the subject of his latest nonfiction film from an unusual perspective: the significance of an unprecedented papal name.

St. Francis of Assisi has long been among the most beloved of Catholic saints, even among those who don’t share his faith, and his most consequential 21st-century namesake remains popular among both Catholics and non-Catholics. Wenders sets out to connect the dots between the medieval Italian friar and the 21st-century Argentinian Pope, making the case that behind their widespread appeal is a message the world needs to hear.

A movie is only as good as its villain, and Wenders’ opening voice-over invokes nothing less than the problem of suffering and evil: natural disasters; terrorism and weapons of mass destruction; threats to the environment and extinction of species. Against this backdrop the “radical answers” of these two men named Francis stand out with fresh urgency.

Neither the life nor the papacy of the former Jorge Bergoglio is Wenders’ subject. Instead, Pope Francis focuses on characteristic themes of his preaching and teaching — particularly those most accessible to viewers of any faith or of none — as well as the engaging personality and common touch with which he advocates them.

These include Francis’ advocacy for the poor, immigrants and refugees; the perils of consumerism and the problem of unjust distribution of wealth; stewardship of the environment and an integral ecology; the horror of war and international arms trade; and the importance of understanding and peaceful coexistence among the world’s religions.

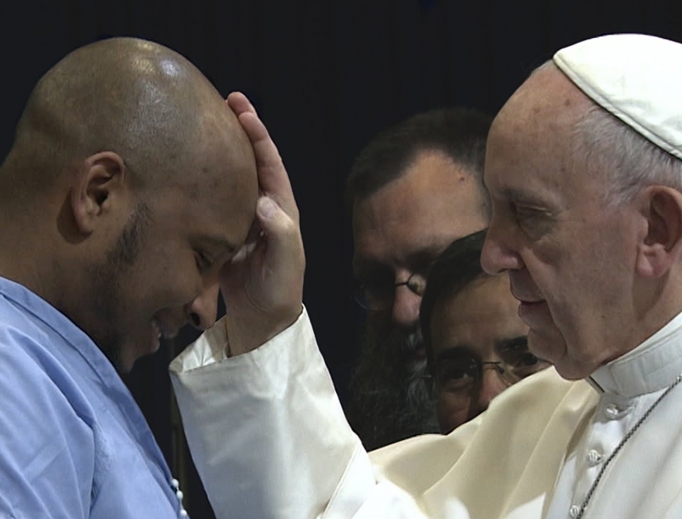

Francis himself brings these themes to viewers, looking and speaking straight into the camera in excerpts of interviews shot for the film in various Vatican City locations, including the Vatican Gardens. Intercut with these interview clips are images from globe-hopping pastoral visits to the Americas, Africa, the Philippines and elsewhere, with the Pope interacting with children, prisoners, hospital volunteers, refugees and disaster victims. The flow of images is subtly enhanced by an unobtrusive string-based score (mostly bowed instruments with an occasional guitar).

As a final touch, Wenders highlights the Franciscan foundations of the Pope’s concerns with evocative footage shot to look like clips from some lost silent-era St. Francis movie that I now wish really existed. (Wenders cross-fades into the first of these clips, shot on a hand-cranked camera from the 1920s, from one of Giotto’s frescoes in the Upper Church of Assisi’s Basilica of St. Francis which the silent footage matches perfectly.)

Focusing on Franciscan answers to global problems means, on the one hand, that Pope Francis is wholly positive in tone. Whatever tensions exist between Francis’ message and his personal failings, or whatever stumbles, gaffes or controversy have marked his papacy, are beyond the scope of Wenders’ interest.

As Pope Francis talks about the horrific crime of child sexual abuse and the necessity of holding accountable guilty priests and complicit bishops, viewers may think of the still-unfolding crisis in Chile, regarding which the Pope has acknowledged “grave errors” on his part, but the film leaves viewers to wrestle with such tensions on their own.

On the other hand, Wenders’ approach truncates Francis’ thought in various ways.

For one thing, there’s little sense of the theological vision underpinning his preaching. Little is said about Jesus — a reference to Jesus crucified in a discussion of theodicy is a notable exception — and nothing at all about Satan or hell, topics particularly notable in the Pope’s preaching.

Ideological selectivity is a factor. The controversial line “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord … who am I to judge him?” is included, but not Francis’ critical views on gender theory. The environmental and economic concerns of Laudato Si (Care for Our Common Home) are emphasized, but there’s no mention of Francis’ indictment of abortion as part of the “throwaway culture.”

And while viewers will learn that Francis is against “proselytizing,” they won’t hear his positive exhortations regarding evangelization.

The full scope of Francis’ thought has something to challenge almost everyone. The film rightly highlights themes and ideas that are stumbling blocks to some on the right — Donald Trump boosters may bristle at the Pope’s criticism of “building walls,” and Wenders himself adds a dig at “alternative facts” — but the members of U2 (who recently endorsed the move to legalize abortion in their native Ireland) could nod their heads pretty much through the whole film.

Maybe not the whole film. Rare exceptions include dismissive remarks about feminism and men’s movements as “isolated” and opposed to sexual complementarity and reciprosity. Even when Francis goes on to talk benignly about the importance of women in leadership roles, his language may sound a bit jarring to more progressive American and European ears.

Not incidentally, the film paints a similarly selective and even misleading portrait of St. Francis, along the usual lines noted by G.K. Chesterton on the first page of his excellent little sketch Saint Francis of Assisi, as a proto-archetype of “all that is most liberal and sympathetic in the modern mood; the love of nature; the love of animals; the sense of social compassion; the sense of the spiritual dangers of prosperity and even of propriety … a sort of morning star of the Renaissance.”

Such hitches and omissions notwithstanding, there’s no avoiding the power of Pope Francis’ genuineness, his expansive Christian humanism and his rapport with people of all walks of life. His celebrated turns of picturesque speech are in evidence: “spiritual Alzheimer’s disease”; “living with the accelerator down”; “globalization of indifference.”

More than once we see tears on people’s faces — and, while one might suspend judgment at the sight of a politician brushing away a tear as the Pope addresses a joint session of Congress, tears on an inmate’s tattooed face as Francis embraces and preaches to prisoners or washes and kisses their (also tattooed) feet on Holy Thursday are another matter.

The mystery of suffering and evil looms above all in a 2014 papal visit to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem and a 2015 multireligious gathering at Lower Manhattan’s 9/11 Memorial.

Similarly, in pastoral visits to a volunteer-run hospital in the Central African Republic, a typhoon-devastated Philippines and a refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesvos, Francis’ active solidarity with those who suffer evokes, however dimly, the Crucified Jesus to whom he pointed when asked about the problem of evil.

Some of the most memorable images emerge from these somber visits: Francis praying silently at Auschwitz or standing in a light rain wearing a translucent yellow plastic raincoat, clasping the hands of an elderly Filipino woman (also in yellow plastic) as she reverently kisses his hands.

There are also lighter moments, such as a droll Q&A with schoolchildren and a gentle papal exhortation to parents to play and waste time with their children.

The film ends with Francis citing a prayer he says he prays daily (ascribing it, following a popular misconception, to St. Thomas More) that includes a petition for a sense of humor. The last shot, of Francis grinning broadly into the camera, lingers long after the credits roll.

If Pope Francis: A Man of His Word isn’t the documentary final word on the 266th pope, in a way it’s something better: It’s a winsome, challenging call to take the Gospel more seriously and to work to make the world around us a little bit better.

Steven D. Greydanus is the Register’s film critic and creator of Decent Films.

He is a permanent deacon in the Archdiocese of Newark, New Jersey.

Caveat Spectator: Some thematic content images of suffering and references to great evils. Might be fine for older kids and up.

- Keywords:

- pope francis

- steven d. greydanus

- wim wenders