Parents of Children With Down Syndrome Applaud Indiana’s Newest Pro-Life Law

The law prohibits abortion sought solely because of a diagnosis or potential diagnosis indicating the unborn child has Down syndrome or any other disability.

INDIANAPOLIS — After an early test showed that Katie Scofield’s unborn daughter, Karinne, could have Down syndrome, Scofield couldn’t get her doctor to confirm the diagnosis during the rest of her pregnancy. It wasn’t until she was preparing to leave the hospital after her daughter’s birth 13 years ago that a nurse began noticing indicators of the genetic disorder.

“I was in the [hospital] room by myself at the time,” said Scofield, who lives with Karinne and her two other daughters in Fishers, Ind. “It caught me off guard. At first I was just in complete shock.”

At 25, Scofield knew little about Down syndrome and didn’t receive much support from her doctor. But she did know she couldn’t abort her daughter, as most women are urged to do when they receive such a diagnosis after an early test, even though it was what her then-husband wanted.

She did her own research about Down syndrome, and Karinne has proved all of her misconceptions wrong, Scofield said.

The 13-year-old has needed treatment for a heart defect, frequent therapy sessions and other care. But now a lively seventh-grader at St. Matthew Catholic School in Indianapolis, Karinne is also a cheerleader and competes in the Special Olympics. Most of all, she has blessed the family “in the most beautiful, wonderful way ever,” Scofield said. “She’s the biggest blessing I never knew I needed.”

Scofield and other parents of children with Down syndrome say they are pleased with the passage last month of an Indiana law that prohibits an abortionist from performing an abortion if he or she knows that the pregnant woman is seeking the abortion solely because of a diagnosis or potential diagnosis indicating the fetus has Down syndrome or any other disability, or because of the fetus’ race, color, national origin, ancestry or sex.

Among other provisions, the law also requires a pregnant woman whose fetus has been diagnosed with a lethal fetal anomaly be given education materials about perinatal hospice care. The law also gives requirements for final disposition of aborted and miscarried fetuses. Indiana law permits abortion until 20 weeks of gestation.

The Indiana law, the second in the country protecting unborn babies diagnosed with Down syndrome, although Oklahoma could be next, has received praise from people who have the genetic disorder, parents and pro-life groups. They say more education about Down syndrome and available resources, along with doctor support, will help dispel parents’ fears. But the law has met with opposition from abortion-rights advocates, who say it unconstitutionally restricts abortion. It is already being challenged legally by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Planned Parenthood. According to Jane Henegar, executive director of ACLU of Indiana, “This law restricts a woman’s right based on her reasons for terminating a pregnancy, and it takes away the very thing a woman needs: the ability to make an informed decision about what could be a devastating situation.”

The purpose of the law is to provide women with other options and to stop discrimination abortions, said Sue Swayze, vice president of public affairs for Indianapolis-based Indiana Right to Life. “We’re trying to put the onus on the medical community to provide a breadth of information,” she said, “not just recommend termination and be done with it, but to give these women and their families more information” about the dignity of the life of a child with Down syndrome.

Down syndrome is a congenital disorder arising from the presence of all or part of an extra copy of chromosome 21, which results in intellectual impairment and physical abnormalities, including short stature and a broad facial profile.

Down syndrome, also known as Trisomy 21, is the most common chromosomal abnormality. Other syndromes involving the presence of an extra chromosome that are more rare and severe include Trisomy 13 and Trisomy 18. Bella Santorum, the daughter of former senator and presidential candidate Rick Santorum, was born with Trisomy 18 in 2008.

In the United States, about 6,000 babies are born with Down syndrome annually — roughly 1 in 700, according to the Centers for Disease Control. As prenatal-testing methods have improved, the total number of babies aborted following a Down syndrome diagnosis has continued to increase, current studies reveal.

“Laws like Indiana’s can help educate Americans that children with Down syndrome are tragically aborted,” said Clarke Forsythe, acting president and senior counsel for the Washington-based pro-life public-interest law firm Americans United for Life.

The high abortion rate for Down syndrome children is due largely to fear and a lack of information, and with support, families can find that a diagnosis doesn’t have to be devastating, said Mary Kellett, founder and director of Prenatal Partners for Life, a Maple Grove-Minn., nonprofit that provides support for expectant and new parents of children with special needs or a life-limiting condition.

“At the time of diagnosis, [Down syndrome] is often presented in such a negative way, and, often, abortion is offered as the only choice,” Kellett said. “It’s a time when families are filled with fear,” but they needn’t be — they and adoptive parents should know the blessings of these special children.

Many couples are waiting to adopt children with Down syndrome, Scofield said.

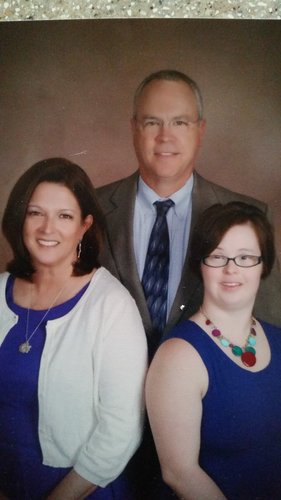

The new law “will prevent those in the medical field from saying, ‘This child has a disability; what do you think about aborting?’” said Patti Shaw of Indianapolis, mother of 30-year-old Katie, who has Down syndrome. “There will be people who get around it, but if it saves one baby, to me, it’s worth it.”

Both Patti and Katie said they are thrilled about the new law. Patti said she never considered aborting Katie when she was given the diagnosis during her pregnancy, adding that her doctors didn’t pressure her.

“I thank God every day,” Patti said of her daughter. “I can’t tell you how different our lives would have been without her.” Patti noted that the family’s Catholic faith has been a source of strength in living with a disability.

Though Katie needed additional care, especially when she was young, Patti disputes the claim that children with Down syndrome are a burden on the state, noting that the family received support from different sources, and her two younger children learned with Katie during therapy sessions.

Now 30, Katie works, volunteers and recently aided a research team regarding passage of the law. “I couldn’t be more happy that it’s a law,” Katie said. Down syndrome, she said, “is a small part of me. It’s not how I look; it’s how you’re seeing me.”

The appearance of Joe and Shelly Lichty’s newborn daughter was their first evidence of Down syndrome, as doctors didn’t tell them about indicators they’d seen on an ultrasound. Shelly recalled the first time she held Elizabeth in the hospital: “As I took her hat off, I noticed there was something different about the shape of her head. Her ears and her nose were tiny, and her eyes had that beautiful almond shape, and I just knew. I cried. My first reaction was fear: Will she be okay? What will the future be like?”

Right away, Shelly realized that her new baby and her family had been chosen for each other and they would be blessed to learn how to love in a new way.

Because not all parents get past the fear, as the Lichtys of St. Paul, Minn., did, they are hopeful that the new Indiana law will provide parents with more education and support. They say Elizabeth is bright, very social and has brought great joy and love to their family.

“It’s a great sign of contradiction that here’s somebody whom people may look at as different or strange, but she’s so joyful and happy, and she really brings that to people,” Joe said.

No longer is being “disability-free” the most important factor, he said, noting that all children have difficulties. God determines each child’s potential, and the job of parents is to help them grow toward it.

When Patti Shaw was pregnant with her daughter, she said she didn’t know how she would be able to help Katie reach her potential. God showed her, though, in ways she couldn’t have imagined.

“I wish anybody who wants to abort a baby for a disability or developmental issues, or because they’re not the right gender, could see into the future — that it will work out,” she said. “Maybe not the way you want it, but better — and that’s how I feel: It has been better.”

Register correspondent Susan Klemond writes from St. Paul, Minnesota.

- Keywords:

- catholic families

- children with special needs

- christian witness

- down syndrome

- indiana

- prolife laws

- prolife legislation

- susan klemond