Catholic-Shiite Dialogue: A Parallel Reality as Conflict Grows Between US and Iran

NEWS ANALYSIS

The Holy See has good relations with the government of Iran, as it does in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, the Middle Eastern hot spots currently in the headlines. Lebanon is on the pontiff’s list of trips this year, and a pilgrimage to Iraq has become a strong probability, depending on security. The Holy See’s representatives have remained in the region without interruption even during perilous times of revolutions and wars.

Although the Catholic Church has no soldiers on the ground, it is directly implicated in regional events for three main reasons: The faithful live there; bishops are respected leaders in Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon; and the Holy See’s diplomatic structure gives Rome insight and intel conveyed to Western governments in the interest of promoting peace — its central mission.

At the height of fluid geo-political turmoil, Vice President Michael Pence visited Pope Francis last Friday for an unusually long, one-hour meeting. The Trump administration recognizes Francis as a pivotal player — besides acknowledging how important the Catholic vote was in 2016. Significantly, Iraqi President Barham Salih met with the Holy Father the next day; both Pence and Salih were consulted on the Pope’s plan to visit Iraq.

So how does the Holy See view the recent crisis involving Iraq and Iran? Was Rome unnerved by the U.S. assassination of Iran’s top general, Gen. Qassem Soleimani? Senior international correspondent Victor Gaetan spoke to Catholic, Shia and Sunni specialists as well as political analysts in Rome and Washington to gain insight into the Church’s view of a region on edge.

This analysis explores the most recent crisis and the roots of ongoing Catholic-Shia dialogue and presents a wider view of Church relations with Iran.

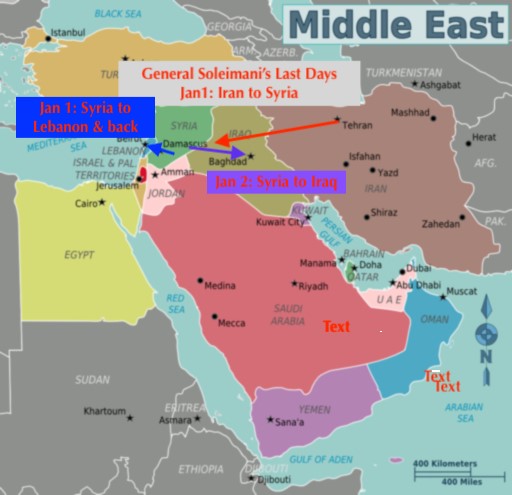

WikiCommons map showing Gen.Soleimani's itinerary in the days before he was assassinated.

For the Catholic Church, every international crisis is personal — because the faithful are everywhere.

In Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, our sisters and brothers in Christ live, precariously, shepherded by bishops with networks reaching across the region and diplomats trained by the Holy See, prioritizing issues of war and peace, at Pope Francis’ direction.

When President Donald Trump ordered the assassination of Iran’s senior military general, Qassem Soleimani, the Vatican wasn’t shocked. The Church typically assesses international relations with a realist’s lens, while pursuing a Christian strategy diametrically opposed to a “decapitation strike.”

With Iran in particular, the Holy See has developed relations with Shiite religious leaders over decades — a practice of engagement that contributed to the 2015 nuclear agreement between Iran and U.S., Russia, China, Germany, France and the U.K. negotiated under President Barak Obama. Examining the Vatican’s approach to Iran presents a diplomatic vision very different from the current U.S. approach, reliant as it is on economic sanctions and military might.

But it’s also necessary to review the lead-up to the crisis. According to sources in Rome and the Middle East, the Church is highly aware of Iran’s trouble-making role in the region.

Popular Unrest

Many both inside the Church and outside were already worrying publicly about the implications of rising tensions between the U.S. and Iran last year.

As popular protest — and in some cases, harsh government response — spread through the Middle East last fall, first in Lebanon, then in Iraq, and, finally Iran, Church leaders closely tracked events. Instability is never positive for minority communities; what Pope Francis describes as a “piecemeal world war” has been calamitous for Christians.

The demonstrations were seen, on one hand, as a revolt against corruption ubiquitous in the political class ruling the region, as well as evidence of economic frustration.

In both Iraq and Iran, experts also saw pushback against a regional strategy masterminded by Soleimani, major general of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and commander of an elite division dedicated to external military operations, the Quds Force — a figure of immense influence.

Soleimani directed military support for Syrian President Bashir al-Asaad and coordinated Russia’s pivotal engagement in the war on behalf of the Syrian government. He was the chief strategist for defeating the Islamic State (ISIS) in Iraq and Syria and repelling Saudi Arabia in Yemen. In Lebanon, he advised Hezbollah, a fighting force that’s also the largest political party.

His heavy hand — and the militias he mobilized — were increasingly resented, however.

For example, as Iraqi Chaldean Cardinal Louis Sako pointed out, Iranian-supported militias have been systematically occupying the Nineveh Plain, a majority-Christian region until the Islamic State raged through and pushed many of these same Christians out of the region.

While Cardinal Sako is trying to encourage families to return, militias are simply buying up or occupying their properties. Representing two-thirds of Iraq’s Christians, the cardinal has been one of the Church’s most prophetic voices.

As Jesuit Father Giovanni Sale explained in this month’s Italian edition of the Vatican-reviewed journal La Civiltà Cattolica (its articles are approved by the Secretariat of State), “Iraqis protesting in the square ask the Iranian ayatollahs not to intrude in their internal matters. Tehran’s attempt to be present throughout the Middle Eastern chessboard, to counter Saudi Arabia, could produce in the region harmful consequences, as well as impoverishing the Iranian population.”

Escalation

Thousands of Iraqi demonstrators marched against Iranian involvement in Baghdad’s decision-making, among other grievances. Between October and November, more than 400 were killed during the protests. A U.S. military contractor in Iraq was killed last month, triggering American retaliation against Iraqi units close to Soleimani.

But it was the general’s link to an aggressive mob at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad on Dec. 31 that seems to have sealed his fate.

According to NBC News, targeting Soleimani was authorized by the president last June, but evidence the general was behind an attack against Embassy of the United States in Baghdad by an Iranian-sponsored militia — a situation that echoed the grotesque 2012 murder of an American ambassador in Libya — was what allegedly provoked the president to “take him out” this year.

Soleimani’s itinerary in the days leading up to his death underscored his kingpin role: From Iran he flew to Damascus, Syria; drove to Lebanon; returned to Syria; then flew to Iraq. He was killed as his car left the Baghdad Airport.

Martin Manna, president of the Michigan-based American Chaldean Chamber of Commerce, explained to the Register that Soleimani “wreaked havoc across the Middle East. Iran has had a stranglehold on Iraq.” The Chaldean community in Michigan has grown from 35,000 to 195,000 in the last 10 years. The Chaldean Catholic Church is centered in Iraq. The Catholic businessman continued, “Most Iraqi officials are privately telling us [Soleimani’s death] was good because they really want Iran out of Iraq. Iran was meddling in their business and causing so much corruption. Iraqis want freedom, democracy, and they don’t want anyone interfering in their government.”

Iraqi Christians also want investment and public awareness, according to Manna: “We want to launch a national education campaign to educate the general public that the Christians are indigenous brothers and sisters who should coexist with Muslims. We are considering opening a Chaldean Chamber of Commerce in Qaraqosh [the largest Christian town in the Nineveh Plain] so we can get more of the diaspora to invest and provide social services to those in need.”

Serving Humanity Together

Under the radar of political and military conflict, two months ago the Catholic Church was pursuing an alternate form of engagement: A high-level delegation from Rome, led by Cardinal Miguel Ángel Ayuso Guixot, president of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, quietly made an official journey to Tehran.

The purpose was to participate in a colloquium, “Serving Humanity Together,” co-sponsored by the Islamic Culture and Relations Organization (ICRO), a division of Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. (ICRO described Soleimani’s murder as a “reckless act of state terrorism.”)

The Catholic and Shiite groups issued a final statement emphasizing the centrality of charity to both faiths, without discrimination toward other religions. Human rights, including freedom of worship, is described as a core principal for both. In addition, concern for “climate change and the environmental crisis” is listed as requiring “urgent” collaboration.

The two sides agreed to meet again in Rome in two years, reconfirming that this Vatican-Tehran dialogue — now a quarter of a century old — is proving remarkably durable. For that reason, it is important to examine the roots of this collaboration.

Although the Catholic-Shiite dialogue began under Pope St. John Paul II, Pope Francis significantly advanced the Holy See’s status in the Middle East by firmly establishing Church neutrality vis-à-vis world powers within the first six months of his pontificate when he helped dissuade the U.S. from bombing Syria.

Respect for the Pope has grown in the Muslim world as Rome has consistently, even persistently, built relations with Islamic leaders, relations which were greatly enhanced by papal visits to Muslim-majority countries: Jordan, Palestine, Albania and Turkey in 2014; Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2015; Azerbaijan in 2016; Egypt and Bangladesh in 2017; and the United Arab Emirates and Morocco in 2019. Francis’ message of peace and fraternity — as well as his personal humility — strike a universal chord in both Sunni-majority and Shiite-majority Islamic countries, as reflected in enormous crowds, appreciation from national leaders and positive headlines in Arabic newspapers. His visits have all been carried on live TV broadcasts despite small Christian populations in most places.

Papal Visit to Iraq?

Abbas Kadhim, director of the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative and former president of the Institute of Shia Studies, confirms regional respect for the “diplomacy of encounter” practiced by the Holy Father.

He told the Register, “It is extremely important to have dialogue because there’s no alternative for reaching mutual understanding. I am aware of good relations between the Vatican and Iran and Iraq. Delegations go back and forth all the time. There are more and more people engaged in this interfaith dialogue.”

Kadhim remembers meeting Pope Francis in Rome as part of a 2018 conference: “You only have time to say a few words, so I said, ‘I hope to see you in Iraq!’ because his presence would help coexistence a great deal.”

Last June, Pope Francis mentioned his desire to visit Iraq, the first ever by a pope, in an off-text remark at a meeting of Church charities: “An insistent thought accompanies me thinking of Iraq — where I wish to go next year — that it may look ahead through the peaceful and shared participation in the construction of the common good of all the religious components of society, and that it may not fall into the tensions which come from the never-ending conflicts of regional powers.” Nine days later, Iraq’s president, Barham Salih, sent a formal letter of invitation.

Iraqi President Barham Salih invited Pope Francis to Iraq on June 19, 2019, nine days after the pontiff mentioned his desire to visit the country.

In fact, the ground was already being laid for such a visit in late 2018, when Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin spent Christmas in the country. (The day before his arrival, Iraq’s Council of Ministers announced Dec. 25 would henceforth be celebrated as a national holiday.)

This month’s crisis in Iraq and Iran has only increased the Pope’s enthusiasm to travel to the region, report sources unable to speak on the record.

“I know Cardinal [Louis Raphael I] Sako [patriarch of Baghdad of the Chaldeans] is working hard to make this visit possible. It is just a question of security,” said Kadhim. “It would be a dream of our generation to see the Pope walk in the steps of Abraham. It would be wonderful.”

USCCB in Qom

In March 2014, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) initiated an unusual venture, sending a five-man mission to the spiritual heart of Iran, its sacred city of Qom. The group was hosted by the Supreme Council of Seminary Teachers for four days of discussions.

“We were very concerned with the rising tensions between the U.S. and Iran, which were long-standing, and we realized there were few paths for dialogue,” Stephen Colecchi, former USCCB director of the office of International Justice and Peace, told the Register.

In June 2016 a USCCB delegation met Iranian religious leaders in Rome and issued a common statement against terrorism, extremism and weapons of mass destruction.

Front row (left to right): Bishop Oscar Cantu, Ayatollah Mahdi Hadavi Moghaddam Tehrani, Ayatollah Abolghasem Alidoost, Dr. Abdolmajid Hakim-Elahi

Back row (left to right): Dr. Stephen Colecchi, Dr. Mohsen Ghanbari, Dr. Ali Abbasi, Cardinal Peter Turkson, Bishop Richard Pates, Bishop Dennis Madden, Dr. Ebrahim Mohseni

One of the participants, Auxiliary Bishop Denis Madden of Baltimore (now emeritus), was the chairman of the USCCB’s Committee on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs at the time.

He described the experience to the Register as “eye-opening,” especially for humanizing the Iranian people.

“Everywhere we went, whether to a restaurant or a shrine or a library, we were very welcome, especially by the students,” the bishop remembered. “The majority of them speak English, and they were glad we were coming to learn about them.”

“At shrines and places of prayer, we saw so many young people,” he added. “We saw the centrality of the religious aspect of life for so many lives.”

He continued, “My impression was that they were very open to the people of the U.S., but they attributed the economic pressure of the embargo to our government.”

Bishop Madden noted, especially for visits in Qom outside meeting rooms, the hosts were very spontaneous and relaxed about having Americans chat with random people.

He was also impressed by the dedication to learning and libraries: “Iran has a very rich history. We went to several libraries, and I was amazed at the restoration process. They had huge restoration laboratories fixing very damaged books, some eaten by insects, but they really value learning.”

As Bishop Madden summarized, “This culture of dialogue is real, and I thank the Holy Father for emphasizing it. We have to try, as much as possible, to learn about others and put aside prejudices. The stakes are too high to do otherwise. When people start flexing their muscles, no one wins.”

Joint Declaration

Not just a sightseeing trip, the American and Iranian religious leaders sensed a breakthrough in mutual empathy, so they tried to find a way to continue discussions, ideally in the U.S.

“We were able to find a lot of common ground,” remembered Colecchi. “Our Iranian counterparts said, ‘Let’s start with our belief in one God and our moral commitments’; then we moved deeper and deeper.”

“We do theology in similar ways. They value both faith and reason, because the two apprehend the one God. They have a cult of saints, key figures from history, who they look to for guidance and wisdom. And they have a teaching authority: We have bishops; they have ayatollahs,” continued Colecchi.

When the U.S. government made things exceedingly complicated for the Iranian clerics to get visas to visit due to presidential elections, the USCCB developed a Plan B, inviting their Iranian partners to meet in Rome. The result, in 2016, was a joint declaration against nuclear arms.

Upon return to the U.S. the American delegates reported on their discussions with the Iranians to the White House, the U.S. State Department, Catholic and secular university campuses and Catholic parishes throughout the country, according to Colecchi and Bishop Madden. However, no institutional exchanges have occurred between Shiite clerics and the USCCB in the last 18 months, according to the USCCB’s Lucas Krouch.

“That shows the impact of political tensions on good things,” rued Colecchi.

Iranian Catholics

But as important as Iran is as a regional power, it is also home to Catholic parishes with roots in the 13th century.

When Pope Francis met with Iran’s three Catholic bishops 14 months ago for their ad limina visit, he heard about progress, stalemate and the status of ongoing dialogue with Shiite Muslim religious leaders who have governed the Islamic Republic since its founding in 1979.

Armenians comprise the largest Catholic community in Iran. They first arrived in Persia as a result of the 17th-century Ottoman War. (The Armenian Catholic Church itself was founded in 1742.) Then, 100 years ago, a genocide drove most surviving Armenians out of Turkey. Approximately 2.5 million Christians were killed. Across the Middle East — in fact, across the globe — Armenian people relocated — and yet continue to maintain their faith with admirable devotion.

Some 10,000 Armenian Catholics in Iran are led by Bishop Sarkis Davidian, appointed by Pope Francis in 2015 to occupy a see that had been vacant for five years. (It is thought that 110,000 Christians live in Iran.)

At his consecration in Beirut, Bishop Davidian told the Register his primary assignment besides delivering the sacraments was to “cooperate for peace.” More recently, Bishop Davidian told the Tehran Times Armenians have full religious and political freedom. As a testament to this freedom, Armenians have two reserved seats in the country’s parliament and, at Christmas, Armenian communities celebrate publicly.

From Archbishop Ramzi Garmou who leads the Chaldean Catholic community of about 4,000 souls and heads the three-man episcopal conference, we hear a more ambivalent report: In an interview with Aid to the Church in Need, he noted that the government forbids priests from saying Mass in Farsi, the local language. Instead, the Chaldean liturgy is said in Christ’s own language, Aramaic.

Yet the Catechism of the Catholic Church and classics such as Augustine’s Confessions translated in Farsi are available in local bookshops — evidence of the Iranian government’s respect for the Vatican, according to Archbishop Garmou.

Trump’s Instincts, Supported by Experts

But if the Catholic communities in Iran are anxious about the future, there is a hint of good news coming out of Washington. Catholic sources close to the White House are privately spreading the word that the president’s instincts are not for war.

They point to his 2007 statement on CNN while being interviewed by CNN anchor Wolf Blitzer, cautioning the U.S. to leave Iraq since it has nothing to gain: “This country is just going to get further bogged down. It’s a civil war over there, Wolf!”

Just three months ago, at the White House, President Trump reiterated his skepticism: “We interject ourselves into … tribal wars and revolutions and all of these things that are not the kind of thing that you settle the way we’d like to see it settled … And it’s time to come back home.”

Trita Parsi, vice president of The Quincy Institute and one of the most respected Iranian American foreign policy analysts, widely broadcast his recommendation to pull out all American troops and start vigorous diplomacy.

President Trump must end “America’s senseless entanglement in Middle East conflicts,” Parsi summarized in an email to the Register.

Standing on the steps of St. Matthew’s Cathedral, eight blocks north of the White House, a national security adviser told the Register, “The Soleimani strike was surgical. No way it will expand into war with Iran. But it’s good the Church stays active and involved. We need Pope Francis’ moral influence.”

Register senior correspondent Victor Gaetan is an award-winning international

correspondent and a contributor to Foreign Affairs magazine and The American Spectator.

- Keywords:

- iran

- vatican

- victor gaetan