A Look at the New Martyrs

Book Pick: The Global War on Christians

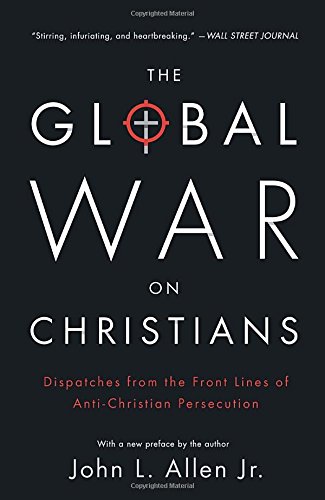

THE GLOBAL WAR ON CHRISTIANS

Dispatches From the Front Lines of Anti-Christian Persecution

By John L. Allen Jr.

Image, 2016.

336 pages, $16

To order: imagecatholicbooks.com

Veteran Vatican correspondent John Allen documents the intensifying spiral of violence and even killing in which “eleven Christians are killed somewhere in the world every hour ... [and] 80 percent of all acts of religious persecution in the world today are directed at Christians.”

The book is divided into three sections. Part I reports on 27 countries where Christians face especially severe religious persecution. Part II refutes five “myths” about anti-Christian persecution (like “nobody saw it coming” or “it’s all about Islam” or some killing is “really” political/ethnic/tribal/random rather than religious). Part III responds with ideas about how people of goodwill might react, from prayer to political action and charitable support.

Allen performs a huge service just by putting “the greatest story never told” on the public radar. Beyond raising consciousness, however, he couples detailed accounts of persecution with nuanced analysis of the complex and varied causes behind it. The hostility towards Christians on the part of other religions or of atheistic regimes are one side of the story; suffering endured, motivated out of faith, in witness to justice and charity is another. Allen also argues that persecution takes two: It is not just the aggressor’s, but also the victim’s, motives that are relevant. If a Christian exposes himself, out of Christian motives, to staying and witnessing to his faith, rather than cutting and running, he is also a victim of religious persecution. A believer who dies out of Christian love to defend his neighbor against the rapacious, the racist or the just plain criminal is just as much a Christian martyr as he who dies in defense of an explicit doctrine.

Let me offer an example: By dying in place of another neighbor, St. Maximilian Kolbe was a “martyr of charity,” not just a political victim of Nazism.

Likewise, as Allen notes, when, in 1997, 36 seminarians in Burundi refused to separate themselves into Hutu and Tutsi (so that their attackers could kill one group but not the other), they were all murdered. They died because of fraternal Christian love, not tribal affiliation.

That said, Allen’s level of detail could also be a criticism: Too many detailed cases of persecution and too dense an explanation of their causes risks either numbing the reader or snowing him under.

With ongoing reports of persecuted Christians, this book continues to be timely.