50 Years Ago: The Assassination of RFK — Kennedy, Politician, Catholic

COMMENTARY: President Kennedy’s younger brother was considered the most devout among the Kennedy men.

It was 50 years ago, June 6, 1968, that Robert F. Kennedy was brutally removed from the national stage by the hand of an assassin.

The country was shocked — yet again. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated mere weeks earlier, and President John F. Kennedy had been killed five years earlier.

Modern audiences, Catholics among them, don’t know RFK as audiences knew him then. Actually, even in June 1968, many RFK supporters didn’t fully know the man, especially his Catholic side. Who was he?

For one, Bobby was the most devout among the Kennedy boys. Those closest to him considered him a prayerful Catholic, despite his sins and vices. At the time of his death, he had 10 children, with another on the way. He attended Mass faithfully and was no stranger to the Rosary — nor was his devoted wife, Ethel, yet another Kennedy woman who suffered much.

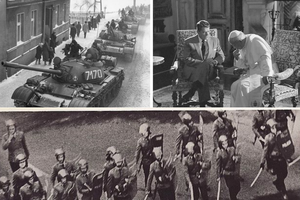

It seems fitting that, in November 1936, a young Bobby was present at a family meeting with a prominent Vatican diplomat named Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli — the future Pope Pius XII — who visited the Kennedy house in Bronxville, New York. He was 10 years old.

When Bobby was away from home studying at St. Paul’s, a private Episcopal school in New Hampshire, he wrote to his mother complaining about the frequent use of the Protestant Bible. She arranged his transfer to Portsmouth Priory, an orthodox Benedictine school.

Biographer Ronald Steel speculates that if RFK had been born into a poor family without a power-hungry patriarch driving the boys into politics, he might have been a priest. Steel observed Bobby’s “fierce brand of Irish Catholicism” and said that he was “at heart, and had always been, a Catholic conservative deeply suspicious of the moral license of the radical left,” particularly its embrace of the drug culture and sexual permissiveness of the ’60s. “He was no champion of women’s rights,” said Steel, “and would likely have been appalled by the very notion of gay liberation, had he ever been confronted with it.”

Jacqueline Kennedy, who observed Bobby’s piety, once remarked that it seemed unfair that JFK’s faith was an issue in the 1960 campaign, particularly in light of Bobby’s devoutness. “Now if it were Bobby: He never misses Mass and prays all the time,” she said.

Bobby’s faith was called upon most acutely with the assassination of Jack in November 1963. He suffered greatly from the death of his beloved brother. The two were extremely close. No two brothers so dominated the Oval Office. The younger Kennedy questioned God the day his big brother was taken Nov. 22, 1963.

That night, alone in his White House bedroom, a friend could hear Bobby cry out, “Why, God?” He was in visible pain, said one friend, “like a man on the rack.”

Biographer Evan Thomas says that Bobby “cast about” to make sense of the despair. At the suggestion of his brother’s widow, Jackie, he began reading the ancient Greeks, where he discovered fate and hubris.

As fate would have it, Bobby Kennedy was facing his own denouement with the hubris of an assassin. For him, the tragic moment arrived late at night, shortly after midnight, on June 5, 1968, at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

It was supposed to be a night of celebration. Bobby had just achieved a grand political victory, having won California in the Democratic Primary. He was surely on his way to the party’s presidential nomination.

But not everyone in that building had similar plans. After giving his inspiring victory speech, Kennedy was led from the podium and toward the hotel exit via a carefully pre-selected back route through the kitchen. But someone was waiting, hiding along that route.

As people pressed in to see the senator, a 24-year-old Palestinian-Jordanian immigrant named Sirhan Sirhan jumped out from behind a cart stacked with trays next to an ice machine and began firing a .22 revolver at Kennedy. He lodged three bullets in his intended victim, one of them directly in the head, entering behind the right ear and piercing into Bobby’s brain.

Bobby went down.

The shooter was seized. Chaos ensued among everyone except for a good Samaritan who came to RFK’s aid. His name was Juan Romero, a busboy at the hotel. The 17-year-old Mexican immigrant had gotten the job at the hotel via his stepfather, a waiter there. He had badly wanted to see Robert Kennedy that night and had attempted to switch shifts with another busboy. When the other busboy refused, Romero paid him to switch. Romero had initially gathered among the crowd to get near the famous Kennedy. He was six or seven people back as he started working his way in. He was small and thin. He made it through and got close enough to extend his hand to the smiling senator. Just as Kennedy grabbed it, Romero heard a loud bang and felt a flash of heat against his face. “I thought it was firecrackers at first,” he later recalled, “or a joke in bad taste.”

It was no bad joke. It was Sirhan firing just past Romero’s shoulder. That was clear as Romero looked down and saw Kennedy laid out.

As onlookers tackled the assassin, Romero knelt down to try to help the senator. The busboy placed his hand under Kennedy’s head to lift him and felt warm blood run through his fingers. Bobby’s wife, Ethel, kneeling in an orange-and-white dress, pushed Romero away. Stunned, Romero began fingering the rosary beads in his pocket. It was the natural thing to do.

“When I was in trouble, I would always go and pray to God,” he later explained innocently. He asked Mrs. Kennedy if she would mind if he gave the rosary beads to her husband. The woman who would soon be praying over her husband with her own beads didn’t say anything.

So Romero pressed the beads into Robert Kennedy’s hand. They would not stay in place because Kennedy could not grip them. Romero wrapped them around the senator’s thumb. When they wheeled him away, the rosary beads were hanging off his hand.

As Kennedy was carried into an ambulance, a woman in the hotel lobby stood nearby exhorting the crowd to prayer. She stood precariously at the edge of a large, ornate pool of water in the lobby, just to the right of the cashier’s window. She held up a set of rosary beads and implored the crowd: “Kneel down and pray; kneel down and pray; say your Rosary!”

Journalist Jules Witcover, who observed the scene, recalled that, immediately, 20 or more people knelt around the pool. One man holding a drink and a cigarette placed both down on the red and black carpet and knelt.

Robert Francis Kennedy, whose middle name was a tribute to St. Francis, patron saint of the Kennedy family, a saint of peace, died 26 hours later at Good Samaritan Hospital. Among those at his side was Mrs. John F. Kennedy. Bobby was only 42 years old. Had he lived to win the presidency, he would have been 43 at his inauguration, the same age as his late brother at his swearing in. His shooter was 24 years old, the same age of Lee Harvey Oswald, the shooter of his late brother. Today, 50 years later, the shooter is still with us. Bobby Kennedy is long gone. Who knows what might have been?

Paul Kengor is a professor of

political science at Grove City College.

His latest book is

- Keywords:

- paul kengor

- robert f. kennedy