Reagan’s Resounding Christmas Addresses

COMMENTARY: Forty years ago, Dec. 23, 1981, the U.S. president gave perhaps the most Catholic Christmas address any president ever has.

President Ronald Reagan’s Christmas addresses were more explicitly Christian than we are accustomed to hearing today.

“Some celebrate Christmas as the birthday of a great teacher and philosopher,” Reagan said in his Christmas Eve radio address of 1983. “But to other millions of us, Jesus is much more. He is divine, living assurance that God so loved the world he gave us his Only-Begotten Son, so that by believing in him and learning to love each other we could one day be together in paradise.”

That’s about as succinct a summary of the Christian Gospel as is possible to fit into a White House speech.

It was 40 years ago, on Dec. 23, 1981, that Reagan gave perhaps the most Catholic Christmas address any president ever has. He began by quoting Chesterton — “the world will never starve for wonders, but only for the want of wonder” — and the topic was urgent, namely the defense of the liberty of a proud Catholic nation, Poland.

He professed his belief in the “divinity of the Child born in Bethlehem, that he was and is the promised Prince of Peace.”

Then the president turned to the need for peace in a troubled world.

Reagan’s first year in office was a terrible year. Economic pain was still widespread. The president acknowledged that, “for some Americans, this will not be as happy a Christmas as it should be.”

“I know a little of what they feel,” he said. “I remember one Christmas Eve during the Great Depression, my father opening what he thought was a Christmas greeting: It was a notice that he no longer had a job.”

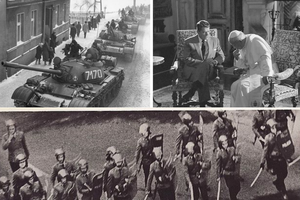

Yet it was not economic policy that marked 1981. It was violence. Reagan had been shot in March, St. John Paul II had been shot in May, and Anwar Sadat, the peace-making president of Egypt, was shot in October. Reagan and the Pope survived; Sadat was killed.

Reagan interpreted the events through a spiritual lens. Receiving Cardinal Terence Cooke of New York at the White House during his recuperation on April 12, 1981, the president told the archbishop: “I have decided that whatever time I have left is for him.”

So when the communist regime in Poland declared martial law on Dec. 13, 1981, effectively going to war with its own people, Reagan added that to a list of enormities in a year full of them. His view was that such outrages were to be met not with dialogue, but denunciation. And so he gave a televised address to the nation 10 days later, one of most beautiful in a presidency known for its magnificent oratory.

“The fate of a proud and ancient nation hangs in the balance,” Reagan said, beginning with Poland’s millennium of Catholic faith. “For a thousand years, Christmas has been celebrated in Poland, a land of deep religious faith, but this Christmas brings little joy to the courageous Polish people. They have been betrayed by their own government.”

“The target of this repression is the Solidarity movement, but in attacking Solidarity, its enemies attack an entire people,” Reagan continued. “Ten million of Poland’s 36 million citizens are members of Solidarity. Taken together with their families, they account for the overwhelming majority of the Polish nation. By persecuting Solidarity, the Polish government wages war against its own people.”

In December 1981, the images of Solidarity’s birth in 1980 were still fresh, Lech Wałęsa at the Gdansk shipyards, the gates hung with holy pictures of the Black Madonna and portraits of John Paul II. Priests offered the Holy Mass inside and heard the confessions of thousands of workers.

“Our government, and those of our allies, have expressed moral revulsion at the police state tactics of Poland's oppressors. The Church has also spoken out, in spite of threats and intimidation,” he added, recognizing that Solidarity was not only a labor movement, but a political and religious phenomenon.

Reagan told the American people that he had met the previous day with Romuald Spasowski, the Polish ambassador who defected just days earlier and sought asylum in the United States in protest of the imposition of martial law.

Then President Reagan asked the American people to show their support for Poland at Christmas.

“Ambassador Spasowski told me that one of the ways the Polish people have demonstrated their solidarity in the face of martial law is by placing lighted candles in their windows to show that the light of liberty still glows in their hearts,” Reagan said. “He requested that on Christmas Eve a lighted candle will burn in the White House window as a small but certain beacon of our solidarity with the Polish people. I urge all of you to do the same tomorrow night, on Christmas Eve.”

“Once, earlier in this century, an evil influence threatened that the lights were going out all over the world,” Reagan continued. “Let the light of millions of candles in American homes give notice that the light of freedom is not going to be extinguished. We are blessed with a freedom and abundance denied to so many. Let those candles remind us that these blessings bring with them a solid obligation, an obligation to the God who guides us, an obligation to the heritage of liberty and dignity handed down to us by our forefathers and an obligation to the children of the world, whose future will be shaped by the way we live our lives today.”

The light did not go out. Exactly 10 years later, on Christmas Day 1991, the Soviet Union itself was extinguished. Poland, her people and their faith, had triumphed. And 40 years ago at Christmas, they knew that they had a stalwart friend, defender of liberty and a fellow Christian disciple in the White House.