Christ Asks Two Men, “What Do You Seek?” And So It Begins…

Like the arms of the colonnade surrounding St. Peter’s, Christ longs to embrace the entire human race.

Among various points of entry concerning the origin and nature of the Christian life, there is one in particular that, for me at least, leaps right off the page.

It is the story of the two fishermen, Andrew and an unnamed other, each of whom had been a disciple of John the Baptist. Who was, to be sure, the very first to give public pronouncement of the appearance of Jesus. Seeing him walk by one day, the Baptizer boldly announced: “Behold, the Lamb of God!” Upon hearing that, the two fishermen abruptly left their teacher, setting off in the direction of Jesus. But at a certain distance, mind you, lest they come too close too soon.

Whereupon Jesus — who has no doubt orchestrated this moment from all eternity — turns around and looks at them, asking the one question aimed at setting the whole drama in motion: “What do you seek?” What is it, in other words, that you want more than anything else, the thing that animates your heart?

The answer they give suggests that perhaps they already know, and that even now they are closing in on it. Because their response to the question just put to them, becomes itself a question: “Rabbi, where are you staying?” Jesus then tells them, but in the form of an invitation, which turns out to be every bit as terse as it is tantalizing: “Come and see.”

This, of course, they accept with alacrity, all hesitancy having been washed clean away. They spend an entire day in his company, we are told, so riveted were they upon every word and gesture of the One whom they are now convinced is the Messiah.

“It is the exceptionality of the figure of Christ,” suggests Luigi Giussani, “that makes it easy to recognize him. For John and Andrew, that Man corresponded to the irresistible and undeniable needs of their heart in a way that was unimaginable. There was no one like that man. … What an unprecedented astonishment he must have awakened in the two who first met him, and later in Simon, Philip, and Nathanael!”

And, to be sure, in countless others as well, down many strange and diverse corridors of history. The human heart, in other words, is driven by so profound and pressing a need for God, for an ultimacy he alone can provide, that the only impetus it requires to get things going is Christ, whose Incarnation becomes the game-changer. For everyone, that is. Like the arms of the colonnade surrounding St. Peter’s, he longs to embrace the entire human race.

“This,” says Giussani, “is the Christian formula, the Christian method.” And what could be more obvious, he continues, than that, “after listening to that Man for hours, watching him speak (‘Who is he who is speaking like this? Who else has ever spoken like this? Who has ever said these things? I’ve never seen or heard anyone like him!’), a precise impression had slowly formed in their heart: If I don’t believe this man, I’ll not believe anyone, I’ll not believe my own eyes!”

Thus does it all begin. Just a couple of guys trying to catch a few fish on a lake. Who, by their simple acceptance of hospitality offered by a mysterious stranger whom they’d accidentally stumbled upon earlier that day, an entire world will be turned on its head. And yet, there was nothing at all odd about meeting a new rabbi, listening to him speak, then deciding to follow him around because he had such interesting things to say.

But not this rabbi. Clearly, there were things about him which, given the singularity of the impression he made, immediately marked him out as different — unrepeatable even.

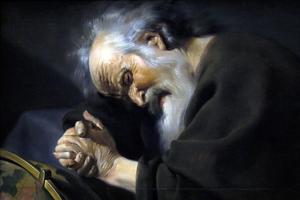

For one thing, neither of the fishermen had chosen him; they were chosen by him. He had seized the initiative, making the initial shattering contact. It was the same with others, too. Think of Matthew, the Levite, into whose life Christ comes crashing through, leaving him no room to maneuver. “Follow me,” he says in a perfectly peremptory way, “and Matthew got up and followed him.” The Caravaggio canvas hanging in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome wonderfully captures that moment when Jesus, looking intently at his quarry, has only to extend his finger unmistakably toward the hapless tax collector, who will thereupon get up and follow, not the money, but the Master.

This suggests yet another striking difference. Which is that those men and women drawn to Jesus, gathered into a growing and admiring group around him, really have no interest in coming together to talk about, say, the Torah. It isn’t any sort of Jesus Seminar that shapes the companionship among them. It is rather the Person of Jesus himself that becomes the organizing principle, not some book.

In fact, he is the book and the whole point of the pedagogy is to study him. He is not only the book but its chief exegete as well. What a dramatic departure from the rarefied world of literary Judaism with all its fussy fixation on Talmudic studies! Jesus is to be showcased — the Incarnate Word himself.

And the class goes on forever. There is never a time when this or that pupil, however precocious his grasp of the material, is qualified enough to graduate, much less assume a learned professorship in what Christianity has come to call the Science of the Cross.

- Keywords:

- Jesus christ

- incarnation