St. John Paul II is a Witness That Great Light Can Emerge From Deep Darkness

Today would have been Pope Saint John Paul II’s 96th birthday. It is interesting to think of how time has passed since his death and to remember that for many of the youth attending World Youth Day, Pope John Paul II is a dim memory. When many were born, his most vital days had passed, and the memories they have of him—if they have any—are of an old man trapped in a body that was slowly freezing up. There are no memories of the young, vibrant and strong skiing pope, the courageous pope who told us over and over again “Do Not Be Afraid”, or even the humorous pope whistling with the youth decades ago at Madison Square Garden.

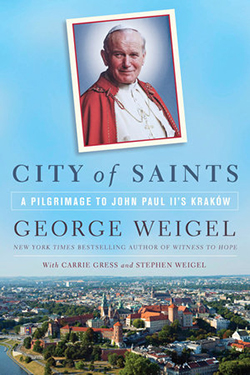

There are, of course, many fantastic resources to help those without memories of the Pope to get to know him, or to remind those of us who knew him why he was so loved. I’m always amazed that, no matter how much I have learned about this saint, there always seems to be more to discover.

One of the people we did not feature in our book, but who made a deep impression upon Wojtyla as a young priest, was Bishop Pietraszko. The auxiliary bishop of Krakow from 1962 until his death in 1988 is well described by Professor Grygiel.

Grygiel, who met Fr. Wojtyla when he was a boy, explained that Wojtyla’s unique perspective on pastoral ministry originated with the relatively unknown bishop. Weigel has made clear in Witness to Hope and now in City of Saints that the young group of laity called Srodowisko brought together by Wojtyla formed him as much as he formed them. Grygiel provides the initial spark from where Wojtyla’s relational attitude came.

The pastoral key, which Grygiel attributes originally to Bishop Pietraszko, is in seeing a priest’s relationship to his flock much like a farmer and his fields. “Our bishops were perfectly aware of the fact that the farmer grows and matures together with the plants entrusted to his care.” So it was with these two farmers and their saplings: “Wojtyla and Pietraszko helped the young people and the young people helped them to seek God and to walk toward him.“

Continuing the farming analogy, Grygiel explains that “culture” is related to cultivation, and raising of crops like the maturing souls. “John Paul II and Bishop Pietraszko were the ones who made us see how culture consists of knowing how to cultivate the earth on which man grows and matures ‘so as to rise again’, to use the expression of C.K. Norwid, a great Polish poet whom they often quote.”

“Culture,” Grygiel adds, “cannot be reduced to learning. On the contrary, nothing is more dangerous to society than learned men who are without culture. Because only culture is life-giving, because the purpose of culture is ‘to rise again’. Culture is either paschal or it is not culture.”

Wojtyla’s style, it has been said over and over again, was to truly be present and engaged in the lives of those around him. He was accessible as a priest, bishop, and even as pope. He knew that “pastoral ministry is not a theory but a form of common life. The theories are supposed to be committed to memory, whereas pastoral ministry requires the wisdom that is born in men who are present to each other.” The future pope’s real secret to pastoral care was truly not complicated. “You can discuss pastoral ministry and plan conferences and publish many documents, but true pastoral ministry is the exchange of gifts between the priest and the lay faithful. Wojtyla understood this very well.”

Life in Communist Poland was a very grey existence where few could be trusted and any public activity was dangerous, so the idea of trying to provide real culture to young people in a society where the secular “culture” was toxic must have been astonishing to the young men and women entrusted to Wojtyla. But even this seemingly desolate ground, where public activity was fenced off and communist ideology poisoned the crops and nourished the weeds, proved to be fruitful for those who loved God. By having to hide their activities, the Communists compelled the members of the Church into living in strictly personal relations. “Thanks also to this dynamic,” Grygiel explains, “in that semi-clandestine state, the relations of friendship and mutual trust became stronger and stronger and revealed to us the beauty of the Church, which made us free from everything that is bound up with mere ownership. Thus God made use of and still makes use of those who deny him.” John Paul II's life is a continual witness that even out of great darkness can come a great light.