Witold Pilecki, the Heroic Polish Spy Who Volunteered to Go to Auschwitz

A recent headline read, “The Holocaust: Many Villains, Few Heroes.” There is, however, one Holocaust hero few people know about: Witold Pilecki. Pilecki not only volunteered to go to Auschwitz, but he lived to tell the world about it.

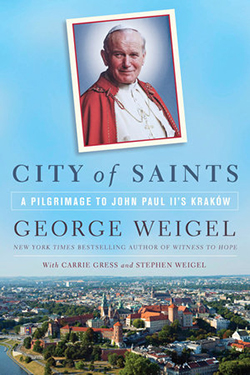

Auschwitz is not far from Krakow, only thirty-five miles west of the city. Although Auschwitz-Birkenau and Oskar Schindler of Schindler’s List are featured in City of Saints, Weigel and I did not discuss the man that many consider to be one of the greatest wartime heroes.

Pilecki’s military career started when he joined the Polish Army to fight the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1920, twice receiving the Cross of Valor for his courage and acumen in battle. In 1931, he married Maria Pilecka and had two children, Andrzej and Zofia. When the Germans invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Pilecki was a cavalry platoon commander and took part in heavy fighting. Despite their best efforts, the Polish army was disbanded in defeat and Pilecki returned to Warsaw.

As a captain in the Polish army and a member of the Polish underground resistance, Pilecki convinced his superiors to let him go to Auschwitz. He was arrested in Warsaw during a general roundup by the Germans on September 9, 1940, and was sent to the notorious camp then thought to be just for prisoners of war.

Upon entering the camp, Pilecki was assigned the number 4859, as the Germans erased as much of his humanity as they could. “We were approaching the gate in a wire fence, on which an inscription: “Arbeit macht frei” (work will make you free) was placed. Later on we learned to understand it well,” Witold wrote in his final report.

For two and half years, he collected data and found ways to get the information to the outside via the Polish resistance. Many of the details of his messages were so horrific – ovens, gas chambers, injections – they were simply dismissed as exaggeration.

In order to survive his ordeal, Pilecki found a way separate the pain in his body with what he describes as a type of exhilaration of “playing” these terrible men. “When the body was continuously in anguish, spiritually you felt sometimes - not to exaggerate – wonderfully”, he explained. “Pleasure began to get nested somewhere in your brain, both due to spiritual experiences and due to the interesting game, purely intellectual, which I was playing.”

At one point in the report, Pilecki writes of visiting the home of an SS member and he grapples with the conflicting realities of life inside and outside the camp and the seemingly incompatible roles of SS soldiers. He writes:

I had already seen terrible pictures in Oświęcim [Polish for Auschwitz] - nothing could break me. Though here, where I was not endangered by any stick or kick I felt I had my heart in my mouth and it was as heavy as never before... [T]here is still the world and people live as before? Here some homes, gardens, flowers and children. Merry voices. Plays. There - hell, murder, cancellation of everything human, everything good... There the SS-man is a butcher, torturer, here - he pretends to be a man. So, where is the truth? There? Or here?

While in the camp, Pilecki was hopeful that the Polish Resistance would be able to sabotage the camp or incite some sort of uprising, but Resistence felt they didn’t have the military force to do it. Even as the Allies, the Soviets, British and Americans were made aware of the camp’s unthinkable evil, none showed the will to do anything to destroy it.

Eventually, after two and half years of back breaking work, lice, freezing conditions, pneumonia, Pilecki realized that it was getting too dangerous for him to stay. He and a few other inmates escaped one night through a poorly secured door of a bakery he had been working in. He then wrote what became Witold’s Report, a comprehensive report on what was happening at Auschwitz for the Allies.

Pilecki took part in the Warsaw Uprising in August 1944 and ultimately survived the war. Auschwitz was finally liberated on January 27, 1945.

Pilecki’s luck ran out after the Soviets took over Poland. He remained loyal to the exiled Polish government in London and gathered intelligence on the Soviet movements within Poland. While doing so, he was arrested in 1947 and after a show trial in 1948, was executed.

For decades the communists suppressed his story until Poland was free again in 1989. On October 1, 1990, Pilecki was exonerated and five years later he was awarded posthumously the Order of the Polonia Restituta. In 2006, he was given Poland’s highest decoration, the Order of the White Eagle, and on September 6, 2013, he was given the rank of Colonel. A street has been named for him in Warsaw.

His life and the “Witold Report” have been published in The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery. In the foreword to the book, the chief Rabbi of Poland, Michael Schudrich, said, "When God created the human being, God had in mind that we should all be like Captain Witold Pilecki, of blessed memory.”