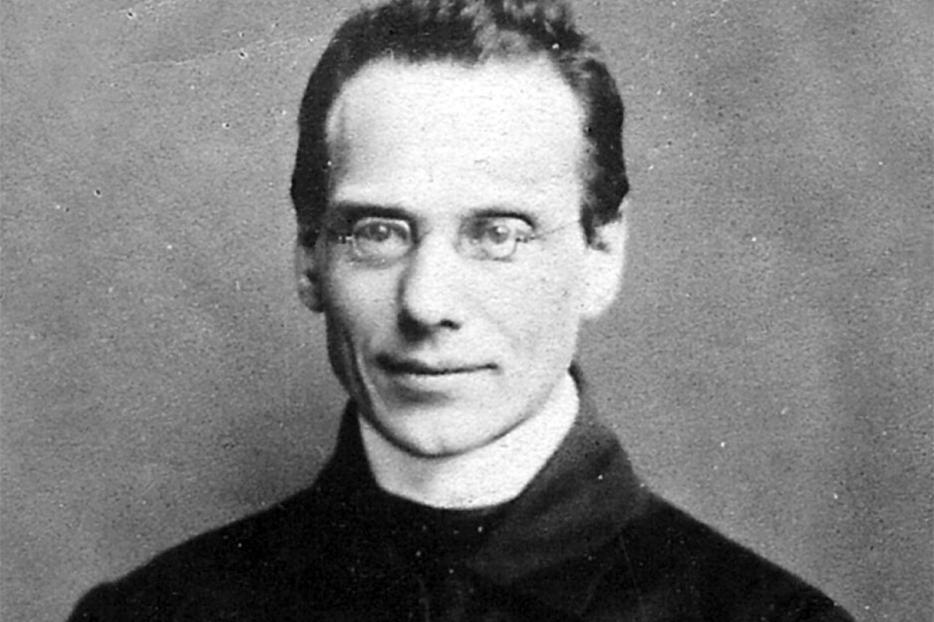

Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos: America’s ‘Happy Saint’

“O help! O help! O holy Mother of God, let me become so inflamed and sanctified that I am not always thinking of breakfast.”

“This morning there departed from the diocesan seminary here one of its most worthy members, Francis Xavier Seelos (born in Füssen, 1819), to leave for North America, and there, after entering the Redemptorist Order in Baltimore, to dedicate himself for his entire life to the important vocation of a missionary. May the Lord accompany with superabundant blessing this truly apostolic undertaking…”

So read the Augsburger Postzeitung on Dec. 9, 1842.

Until three weeks before, only Francis´ father had known of his son’s intention to become a priest in the United Sates. On one of their “walking trips,” Francis had confided to Mang Seelos his desire to be missionary. Mang gave his blessing. It came as no surprise to Mang that his son had decided to be a priest. He had played Mass as a child and prayed the Rosary by himself after the family prayers. When he started school after a sickly childhood that it didn’t seem he would live through, he proved himself one of the most brilliant pupils at the Füssen primary school.

Though Mang was a skilled weaver and had a small farm to provide for the basics, he could not afford to send Francis to secondary school. But with a scholarship from the town to cover tuition and incidentals, plus the help of the parish priest in arranging for his room and board, Francis was able to continue his education in Augsburg, about 40 miles away.

One family provided a bed and roof for the night, while other families gave the young student “meal days,” a place at their table for the main midday meal. For breakfast and dinner, Francis usually munched on some bread. His parents also sent him a small allowance every week, but that went right through his hands. Anyone in need of money came to him. “Banker Seelos” they called him at school, except that he didn’t keep accounts for repayment.

“They are poorer than I am and do not have any meal days or money,” he explained to his parents when they heard what was going on. “I cannot stand seeing them go without, as long as I have something.”

Francis had also inherited his father’s jolly spirit and love for the outdoors and singing. At sung Masses, he would get so carried away with the music his practically shouted, oblivious to the remonstrations of his friends.

On his vacations from school, he took long “walking trips” through the countryside shrines and minor pilgrimage churches. When he was 16 he walked 15 hours to the Benedictine Monastery at Einsiedeln and asked to be admitted. The monks rejected him. He came home dejected but didn’t, ultimately, change his intention to be a priest and religious. Still, when he graduated from high school, he decided not to go to the philosophy course offered by the Benedictines in Augsburg. Instead, he went on to the University of Munich on another scholarship from the Füssen Town Hall. He studied philosophy, but he was not in the seminary. Instead, he lived with two cousins and his brother, learned dancing and fencing and violin, and became a connoisseur of tobacco, which he snuffed with relish.

He advanced to theology studies, but still had not entered the seminary. In a dream one night, he saw himself as a priest at the altar, holding the consecrated host in his hand ready to give the congregation Communion. Then he looked up, distracted by an “unusually attractive” young woman. He “immediately recommended her to God and strove only to know the will of his divine master.” The appeals of the Redemptorists for missionaries in America also reached his ears.

“Today we will not write,” he told his brother Adam, who was studying a trade in Munich and had come for his weekly writing lesson that Sunday in 1842. “Last night the Blessed Mother appeared to me. I have to be a missionary.”

On his summer vacation, Francis told his father about his decision to be a missionary and applied to the Redemptorists in Maryland, though the two men decided it was best to keep it between themselves for the time being. Francis returned to Füssen in September, this time as a seminarian — the best way, he thought, to await the answer of the Redemptorists. As father and son said goodbye, Mang silently pointed to the sky. Francis understood the message. They would see each other again in heaven.

In November Francis received his acceptance letter from the Redemptorists. Like his patron saint, he did not to make a final visit home before leaving for the missions. Instead, he spent the months before his journey to America with the Redemptorists in Altötting, and broke the news and said farewell to his family by letter.

“Even though I am far away, love remains and unites us eternally here in prayer for one another. Love has united us, love does not mean parting, love will always remain, love will unite us again in the beyond,” he wrote his sister Antonia, his confidant from childhood. “I am writing this not without tears and you will be crying too… Farewell forever, dearest unforgettable sister!”

Francis set sail for America from La Havre on March 17, 1843, and landed in New York a month later on Holy Thursday. After a short stay with the Redemptorists in New York, Francis made his way to Baltimore for his novitiate. He made his first vows on May 16, 1844, and was ordained a priest at the parish church of St. James the Lesser six months later on Dec. 22, 1844.

He spent his first eight months as a priest right there at St. James the Less in Baltimore. Released from the novitiate and seminary studies into the world of parish work, he was deeply encountering the differences between his Bavarian homeland and his American mission land. “The bedbugs, insects, the religious sects, the language and so many things more” were his chief annoyances. He would never preach easily in English. In America, he also found, reigned “the vulgar spirit of speculation, business, money, the coldness and dryness of the people — nowhere a cross or a church of pilgrimage — no happy faces, no songs, no singing, everything dead.” Still, he was happy.

“Nonetheless, I love my life… I am always as healthy as can be and do not want for the smallest thing — the best food, decent clothing. We have heat and water in the house, which can be used all through the night,” he wrote home.

He was then transferred to St. Philomena Church in Pittsburgh, were Father John Neumann was pastor and superior. The future bishop and saint became a true guide to Father Seelos in the midst of demanding priestly duties.

In Pittsburgh the Redemptorists had in their charge not only the main urban parish but also churches and outposts for a hundred miles around. Initially, the novitiate had been relocated to the parish as well. The newly ordained took his complete portion of Masses and preaching near and far, confessions, visits to the sick, and catechism classes. He preached in English, German and French.

Father Seelos had already made a reputation for himself as a homilist. He had a knack for explaining the faith in simple terms applicable to his hearers, and his style was engaging, even entertaining. His homilies could be one-man shows where the characters from the Gospel quipped back and forth before he summarized the lessons of the day’s Gospel. He usually ended with a heartfelt call to for all to bring themselves to the mercy of God.

“Ah, you sinners,” he would say, stretching his arms wide, “who have not the courage to confess your sins because they are so numerous or so grievous or so shameful. O, come without fear or trembling! I promise to receive you with all mildness. If I do not keep my word, I here publicly give you permission to cast it up to me in the confessional and to charge me with a falsehood!”

The line outside his confessional was always long.

In 1848, he was, to his surprise, appointed novice master. It was a short-lived assignment, as the novitiate was transferred to Cumberland, Maryland, six months later. That same year, Father Seelos made his annual retreat and dug in even deeper into his spiritual life, committing himself more seriously than ever to reaching holiness in his vocation.

“As long as there is breath in me, and with your help and grace, I will never give up. I am fully prepared for everything and give my body, and my soul completely into your hands as a holocaust,” wrote in his retreat notes as the 10-day spiritual exercises began.

But it wasn’t easy.

On the fourth day he wrote, “O help! O help! O holy Mother of God, let me become so inflamed and sanctified that I am not always thinking of breakfast.”

Indeed, the life of a priest in America at that time could be genuine sacrifice of body and soul — especially in a time of widespread anti-Catholicism. Father Seelos had rocks pelted at him in the street, was beaten during a sick call, and was almost thrown overboard on a ferry when he knelt out of respect for the Blessed Sacrament he was carrying.

Neither his successive appointments as pastor of increasingly larger parishes nor the harshness of times could change his gentle disposition or his availability to everyone. He talked for half an hour with the poor woman or the half-witted man who came to the rectory for a meal. When a fellow brother chided him for wasting his time, Father Seelos replied simply that he could not receive some people kindly and others not. He kept vigil at the bed of sick child so the mother could rest, and did a pile of laundry for another poor woman sick in bed. He gave his gloves away to a poor man he passed on the street.

No one was rushed out of the confessional. He sincerely wanted to hear the penitent’s life story and see how he could best advise him. When visiting the sick, he took time for a friendly visit with the patient. He was known to sleep in his clothes near the door to more quickly answer the inevitable nighttime sick calls. His most famous sick call was the night he was asked to come to the local whorehouse for a dying prostitute. He didn’t hesitate, even though he knew it would make the papers.

“Let them talk,” he said. “I saved a soul!”

Eventually, his untiring ministry caught up to him. Like he did many days, he had been sitting in the confessional of St. Alphonsus Church in Baltimore for hours in the late winter cold. He stepped out, stretched and started to exercise to get his blood moving. A stream of blood spewed out of his mouth. He had had a hemorrhage in his throat. He didn’t complain, but his confreres could see that he was not well and wrote to the provincial superior that Father Seelos needed to see a doctor. He was hospitalized for a month.

Meanwhile, the Redemptorists were looking for a new prefect for their seminary. Under the previous prefect of students, the atmosphere had become morose and unhealthy. Their sights landed on Father Seelos, who came recommended as “a saint in spirituality and an angel in sweetness.”

Father Seelos taught some of the theology classes and set the rhythm of life at the seminary. To prayer and study, he added walking trips and swimming at the beach in summer. He also allowed the seminarians to put on plays. Curious when he heard about it, he briefly joined the “Laughing Club” three of the students had formed. The rules were simple. At any given moment and without warning a member could be called on to make a joke, but no one was allowed to laugh until signaled by the joke-teller. Those who could not hold out got a penance. Father Seelos had to quickly leave the club, as, he complained, he was getting too many penances.

Though the number of seminarians had doubled, not all of the Redemptorists approved of Father Seelos or his innovations. Especially opposed was the priest he had replaced. The man’s viperous letters, and those of others, to the congregation’s highest authority in Rome finally prevailed. Father Seelos was notified without explanation that his replacement was being sent from Europe. He was not given the chance to defend himself against his detractors, either. Though it hurt, his response was a chatty letter to the superior general.

“The whole change went forward without any difficulty because all were happy to see it as the greatest of blessings and accepted the new prefect with gratitude… I will be happy to go hand in hand with the new prefect and help him in whatever I can. It seems to me the choice could not have fallen on a better and more capable father,” he wrote.

His ousting from the seminary landed Father Seelos in his favorite assignment of his priesthood — leader of a mission band. A 19th-century Redemptorist mission was the tent revival of Catholicism. Working in groups as small as two or as large as six, Redemptorists crisscrossed the United States from the east coast to the Great Plains, taking parishes by storm and preaching, teaching and hearing confessions for a week or so. They could spend up to 12 hours a day in the confessional.

A mission revived and invigorated Catholics of all spiritual states and marked a spiritual high point for the community as whole. As Father Seelos wrote, one congregation was so enthused and grateful they nearly carried the priests off like they had just won the World Series. For two years, from 1863 to 1865, he and five other Redemptorists preached and heard confessions though 10 states from New York to Missouri. Father Seelos was in his element.

“I love the mission more than anything else,” he wrote to his sister. “It is properly the work of the vineyard of the Lord.”

After his time on the mission trail, he was sent back to parish ministry, first briefly to Detroit, and then to New Orleans. With its hot, humid climate that was perfect for breeding infectious diseases, its pockets of poverty, and the influx of people through its port, New Orleans had a reputation as dangerous place. Father Seelos calmly foresaw that here his life would end.

“I will be there one year and then I will die of yellow fever,” he told a School Sister of Notre Dame on the journey to his last parish.

This is exactly what happened. For one year, he continued as he always had — humble, especially kind to the poor and sick, consoling sinners in confession, encouraging Catholics from the pulpit and available to everyone, until the yellow fever epidemic struck in 1867. Father Seelos ignored his first symptoms, of course. His superior sent him to bed. Initially, it seemed he would pull through. The fever had passed, but he was still languishing three weeks later. Then he worsened again. The infirmarian asked if he had any matters of family inheritance that needed to be settled.

“No,” he smiled, “Before I came to America we settled everything. I get nothing and they also get nothing.”

For the next few days we went in and out of delirium. He would preach wildly in German and English and then fall asleep. Once, he woke up, suddenly, startled.

“Where am I? Am I dead?” he said.

The infirmarian laughed. Then Father Seelos did, too.

The morning of Oct. 4 looked like it would be his last day on earth. His fellow priests and brothers circled around his bed and sang a Marian hymn that Seelos loved. He was visibly relieved, lifted up. He remained conscious to the end, murmuring prayers as his illness pushed him toward death. He died that evening.

Sources:

- https://seelos.org/historical-timeline/

- The Life of Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos, Redemptorist by Carl W Hoegerl, CSs.R, and Alicia Von Stamwitz

- Keywords:

- Francis Xavier Seelos