Beatified Chimbote Martyrs

Franciscan Missionaries Witness to Power of Christian Love

On Dec. 5, three missionaries killed in Peru by communist terrorists — the Polish Franciscan Fathers Zbigniew Strzałkowski and Michał Tomaszek and the Italian diocesan priest Alessandro Dordi — will be beatified.

Paradoxically, both the missionaries and terrorists had a common goal: to empower the poor. However, the missionaries saw Christian love as the solution to inequality, while the atheist terrorists chose hatred.

Although today’s Peru enjoys impressive economic growth, in the 1980s, the South-American nation was plagued by poverty and violence. As a response to the growing pauperization of Peruvian society, the Communist Party of Peru, called the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), engaged in acts of terrorism. It was influenced by the philosophy of Chinese revolutionary Mao Zedong (who killed more people than Hitler and Stalin), positing constant war to liberate the working class.

Although the Shining Path made Peru a dangerous country, many European priests chose to become missionaries there. They included Polish Franciscans Strzałkowski (1958-1991) and Tomaszek (1960-1991), who entered seminary shortly after their countryman St. John Paul II was elected pope.

“Our entire generation was deeply influenced by this pope and his teachings,” recalled Father Zbigniew Swierczek, a Franciscan in Krakow, Poland, who was friends with the Polish priests in seminary. “They came from families where faith was treated seriously, and so they were radical witnesses of Christ.”

Another Polish priest, St. Maximilian Kolbe, who was canonized in 1982, influenced his fellow Franciscans. Although St. Maximilian is best known for volunteering his life in Auschwitz to save the life of a fellow prisoner, he was also a missionary in Japan and used the media to spread the faith. Inspired by their saintly brother, Fathers Strzałkowski and Tomaszek decided to become missionaries and evangelists.

“In seminary, we greatly admired Father Kolbe because he was very traditional in his faith and his Marian devotion, yet he was also someone who excellently used new technology for evangelization,” Father Swierczek explained.

In 1988, Father Strzałkowski and his fellow Franciscan Father Jarosław Wysoczanski went to Pariacoto in the Peruvian Diocese of Chimbote, and Father Tomaszek followed the next year. In the 1980s, Pariacoto was a poor, remote village in the Andes, mostly inhabited by Indians. Their poverty, however, was not only material in nature: Before the Polish Franciscans established a mission there in 1989, priests would only sporadically come to Pariacoto. As a result, the villagers had limited access to the sacraments. While most Pariacoto residents called themselves Catholics, their Mass attendance was infrequent, and concubines were the norm.

The Polish friars’ new parishioners took an immediate liking to them. In 1989, a great drought hit Peru; in response, the Polish friars brought food from the international Catholic charity Caritas to Pariacoto and appealed to charities for infrastructure that would ease access to water and teach the people how to create a local water-pipe network.

Above all, however, the Franciscans worked to revive their new parishioners’ faith. They catechized them and showed them videos about the lives of the saints. Young men were encouraged to become altar servers.

Naturally, the Shining Path saw this as a threat. In the atheistic Marxist ideology, religion is “opium for the masses” that makes the poor hope for a peaceful afterlife, instead of fighting for better material conditions now. Because there is no God to be accountable to in Marxism, morality becomes relative. Thus murder becomes justifiable.

The friars had heard about the Shining Path’s brutality and hatred for the Church. Pariacoto itself was in a state of lawlessness: In February 1990, the terrorists destroyed the local police station. Yet the friars refused to return to Poland or transfer to a safer mission.

On Aug. 9, 1991, masked Shining Path terrorists stormed into the presbytery at Pariacoto. They accused the priests of supporting the “Yankee imperialist” Caritas and weakening the people’s revolutionary potential by encouraging religion. The terrorists demanded Fathers Strzałkowski and Tomaszek get into a car stolen from the monastery (Father Wysoczanski was on vacation in Poland at the time). They were driven off into the wilderness and shot.

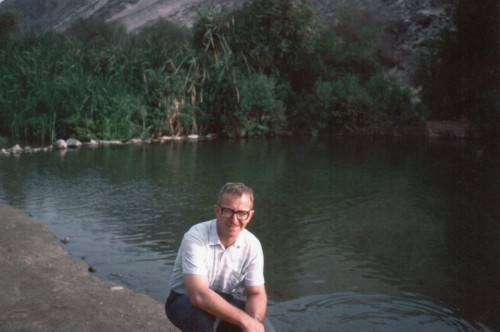

The Polish priests were friends with Father Dordi (1931-1991), who had been a missionary in the Chimbote Diocese since 1980. Previously, Father Dordi had ministered to Italian immigrants in Switzerland and served as a worker-priest in Swiss watch factories. Thus, Father Dordi knew the concerns of the working class.

In Peru, Father Dordi served in the Santa parish. Like Fathers Strzałkowski and Tomaszek, he was committed to his parishioners; he was particularly devoted to Santa’s farmers, helping to implement rural development programs. As soon as Father Dordi learned about his Polish-Franciscan friends’ fate, he kept telling his closest collaborators that he knew he would be next. However, he declined his bishop’s offers to return to Italy.

Subsequently, the Shining Path considered Father Dordi a threat, too. On Aug. 25, 1991, when he was returning from a chapel in the diocese to baptize children and celebrate Mass, the communists set up an ambush. After Father Dordi left his car, they shot him.

In past years, the people of the Chimbote Diocese have grown in devotion to the missionary trio of martyrs, and many claim to have received graces through their intercession.

Their devotion will now be rewarded.

“The beatification is a historic day,” Father Swierczek explained. “These three priests will be the first beatified martyrs of Peru, and Fathers Michał and Zbigniew will be the first beatified Polish missionary-martyrs.”

After the 1991 martyrdoms, the Shining Path failed to attract recruits in the Chimbote Diocese. In the 1990s, the Peruvian government intensified its crackdown on the organization, and many of the Shining Path’s leaders were jailed.

The Chimbote martyrs show that, for true social justice to be achieved, it can only be based on Christian love, not on reducing the person to economic categories.

Filip Mazurczak writes from

the Atlanta area.

Polish priests photo, public domain;

Italian priest photo, courtesy of Archive of the

Sisters of Jesus the Good Shepherd.

- Keywords:

- Nov. 29-Dec. 12, 2015