What the Debate on Celibacy Gets Wrong — and What Church Teaching Gets Right

COMMENTARY: Proposals for married clergy often reveal a functional view of the priesthood that loses sight of its spiritual fatherhood.

Two years ago, a group of young men in Spokane, Washington, posted an ad on the Craigslist volunteer page for a “Generic Father for Backyard BBQ.” Applicants, the ad continued, should have 18 years’ experience as a father, 10 years of grilling experience, and “an appreciation for cold beer on a hot summer day.” The ad went viral, and more than 100 men submitted applications to be a generic dad.

The ad is humorous because, as everybody knows, there is no such thing as a generic father. Any father worthy of the name is not just a functionary, turning up every now and again to do a few “dad things.” And yet, some arguments surrounding priestly celibacy seem to envision precisely that kind of fatherhood for priests.

In a previous commentary (and a recent book), I argue that discussions about priestly celibacy often fail to recognize its powerful contributions to the spiritual fatherhood of priests. Such arguments, I realize, do not carry much weight for those who are not practicing Catholics.

However, after the most recent spate of scandals and the ongoing shortage of priests, even many faithful Catholics are starting to lose confidence in celibacy. “All well and good, Father,” I hear them saying, “but pretty words do not address the problem. You are clinging to an outdated practice. We need more priests — and that means ordaining married men, period.”

Does it?

Nobody more than a priest understands the need for the sacraments, and especially the Eucharist. There is certainly a need for more priests in many parts of the world. In some regions, the situation is critical. Perhaps ordaining married men would alleviate that shortage in the near term. Then again, perhaps it wouldn’t — plenty of Protestant communions with married clergy also suffer from a shortage of ministers.

But I do not think that is the first question to ask. We must consider not whether we would have more men for ordination with married clergy, but, more directly addressing the issue, what ordination means in the first place. For many Catholics, endlessly barraged by scandalous reports of unfaithful priests and bishops, the priesthood is no longer the beautiful vocation it once was. Many no longer see the priesthood for the radical vocation it is.

Instead, shaped by a view of professional work in the wider culture, some have begun to see priests in a largely administrative or functional light. Priests are men who show up to celebrate the sacraments; anything beyond that is the proverbial icing on the cake.

And yet, just as there is no such thing as a generic father who just shows up to do “dad things,” neither is there a generic spiritual father who simply appears on Sunday morning to do “priest things.”

Every priest is a mediator of a marvelous love story. He stands in the place of Christ himself, the one Priest of the New Covenant — the celibate Priest who opens his heart and lays down his life for his people without reserve. Jesus carefully prepared his apostles, his first priests, to do the same. In his preaching, healing, forgiving and caring for the poor, he taught them that their vocation would be total and all-embracing. Such is the radical and unalterable nature of the priesthood that comes from Jesus himself.

Once this understanding of the priesthood is absorbed, the difficulty of married clergy becomes obvious — because marriage is also intended to be a radical gift of self. I know many married priests (Eastern Catholics and former Episcopalians) who are exceptional men. But they all must manage the inevitable tension between their vocation to priesthood and their vocation to marriage — both “total” commitments — and they do so more or less successfully. It is priestly celibacy that helps a man realize and protect the radical nature of his vocation, his all-embracing call to spiritual fatherhood.

In fact, relaxing the requirement for celibacy would not only forfeit many of the graces of supernatural fatherhood in the present; it would also endanger those graces in the future. As I’ve written before, there is little doubt that celibacy, however beautiful a gift to the Church and the priest himself, is a charism that is difficult to receive, especially in today’s world of sexual saturation and confusion. Celibacy enkindles a noble generosity in the heart of a young man, but like all deep human loves, the capacity for celibacy takes time to mature.

It is true that some seminarians would still choose celibacy, even were it optional. However, if they knew they could later be ordained as married men, who could doubt that many — who otherwise could receive the beautiful grace of celibacy — would simply assume such a sacrificial gift is not for them? How many graces of celibacy would be forfeited by making it unnecessarily difficult for those in priestly discernment to receive this gift?

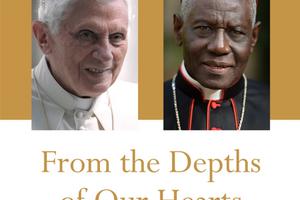

The undeniable need for more priests demands a response, but let it be a response of faith. We do not just need more priests — we need holy priests. We need spiritual fathers, not simply dispensers of the Eucharist. In 1990 Cardinal Ratzinger told a group of seminarians, “It is probable that all the great crises in the Church were essentially connected to a decline in the clergy, for whom intercourse with the Holy had ceased to be the fascinating and perilous mystery it is, of coming close to the burning presence of the All-Holy One, and had become instead a comfortable craft by which to secure one’s daily needs.”

We are surely living through one of those “great crises” today. Ordaining married men might obtain for us more priests, and hence greater access to the sacraments, at least for a while. But such proposals often betray a functional, superficial view of the priesthood. They are illusory and risk turning it into a “comfortable craft” that is foreign to the vocation.

What, then, to do? In the past, when large swaths of the planet had not heard the Gospel, other countries stepped up to send missionaries. Today, new apostles — often heroic and generous laypeople — are once again on the move. New ecclesial movements have brought life to areas once thought spiritually dead. Priests and religious from vocations-rich regions of the world are serving the very nations that evangelized them. In addition, pockets of vibrant Catholic culture and flourishing families are gaining strength all around the world. Many seminaries have dramatically improved the selection and formation of celibate priests. These are the signs of life that promise a far more substantial response to our present crisis, a response which should be fanned into flame.

In the end, however, the crisis will be mitigated only by a conversion of hearts. It will be mitigated by Catholics, clerical and lay, making sacrifices for the good of the Church and getting on their knees in prayer. In a word, it will be mitigated by holiness. Anything less is simply fool’s gold.

There are no generic fathers. The spiritual paternity to which priests are called is real and tangible and profoundly human. Celibacy is a sacred gift of the Lord, the most fitting accompaniment of the holy priesthood and one that best enables us to live our vocation as spiritual fathers. Every generation of Catholics has been tempted to tamper with the precious gift of celibacy for the sake of immediate gain. In each case, deeper supernatural remedies were chosen instead. Let us pray that our generation does the same.

Father Carter Griffin is a priest of the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C.