Year of Mercy More Than Two Centuries in the Making

COMMENTARY: The jubilee year, with this renewed emphasis on the God who is rich in mercy extends to the 19th century and the depredations of the French Revolution.

When Pope Francis opens the holy door for the Jubilee of Mercy on Dec. 8 in Rome, he will be drawing attention in a pastorally imaginative and compelling way to the conviction, growing in the Church for nearly two centuries, that the mercy of God is at the heart of her proclamation to the world.

“The theme of mercy has been strongly accentuated in the life of the Church, since Pope Paul VI,” Pope Francis said recently, in an interview with Credere, the journal of the jubilee year. “John Paul II stressed it strongly with Dives in Misericordia [his encyclical on mercy], the canonization of St. Faustina and the institution of the feast of Divine Mercy on the octave of Easter. In line with this, I felt that it is somewhat a desire of the Lord to show his mercy to humanity. … It is the relatively recent renewal of a tradition that has, however, always existed.”

Of course, the mercy of God has been central to the Christian Gospel since the beginning. Indeed, the title of St. John Paul II’s encyclical, Dives in Misericordia, is biblical, taken from St. Paul, who writes that God is “rich in mercy” (Ephesians 2:4). The Holy Father, though, is right to note that, in recent times, the Church’s magisterium has emphasized Divine Mercy in a more urgent way.

The date for the opening of the holy year, Dec. 8, was chosen because it marks the 50th anniversary of the closing of the Second Vatican Council. St. John XXIII, in his famous opening address for Vatican II — so famous that its date, Oct. 11, was subsequently designated as his feast day — spoke of a Church that prefers to use the “medicine of mercy” for the needs of our time, scarred by so much hatred for God and man, degradation of human dignity, violence and war. This Advent also marks the 35th anniversary of Dives in Misericordia, and this Christmas is the 10th anniversary of Pope Benedict XVI’s first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est (God Is Love).

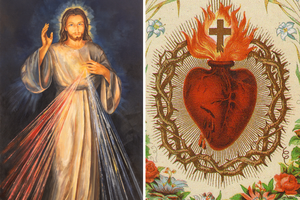

The jubilee year, then, comes in strict continuity with the Holy Father’s immediate predecessors. Yet this renewed emphasis on the God who is rich in mercy extends further back, to the 19th century. After the depredations of the French Revolution and its aftermath, the Church discovered anew the merciful heart of Jesus as the antidote to the acids of a rising secularism and anti-clericalism. The apparitions of the Sacred Heart to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque at the end of the 17th century in France had already spread beyond its borders in the 18th century. In 1765, Pope Clement XIII instituted the feast of the Sacred Heart at the request of the Polish bishops. This turn toward the Sacred Heart, counter to a vague theism or harsh Jansenism, gathered great force in 19th-century piety. In 1856, Blessed Pius IX extended the feast of the Sacred Heart to the universal Church. Finally, in 1899, Pope Leo XIII declared that the jubilee of 1900 would be the occasion of a consecration of the entire world to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

“Considered from a mystical point of view, the 19th century was the century of the Sacred Heart,” said Msgr. Maurice d’Hulst, founder and first rector of the Catholic Institute of Paris.

By the midpoint of the 20th century, most parishes, to say nothing of Catholic homes, would have images of the Sacred Heart prominently displayed. It had become a key part of Catholic piety. Pope Pius XII, commemorating the centenary of the universal feast of the Sacred Heart in 1956, explained its significance in terms of mercy:

“Since our divine Redeemer, as our lawful and perfect Mediator, out of his ardent love for us, restored complete harmony between the duties and obligations of the human race and rights of God, he is, therefore, responsible for the existence of that wonderful reconciliation of divine justice and divine mercy which constitutes the sublime mystery of our salvation.”

The eruption of iconoclasm immediately after Vatican II laid waste to much Sacred Heart imagery, but by the turn of the 21st century, something had replaced all those images of the Sacred Heart. Today, the image of Divine Mercy is near-ubiquitous. To a great extent, it has replaced the Sacred Heart because it is largely the same devotion to the Heart of Christ, wounded by love and the fount of mercy.

In several significant ways, the pontificate of St. John Paul II took up the themes and vision of the greatest of the 19th-century pontificates, that of Leo XIII. So as Leo put the Sacred Heart at the center of the jubilee of 1900, John Paul put Divine Mercy at the heart of Jubilee 2000. He made St. Faustina Kowalska the first saint of the third millennium and extended the feast of Divine Mercy to the whole Church. Again, as with the Sacred Heart, the Polish bishops were the pioneers — Divine Mercy Sunday had begun there in 1993.

“The message of Divine Mercy has always been near and dear to me,” said John Paul when addressing St. Faustina’s fellow sisters in 1997 at the shrine in Krakow. “It is as if history had inscribed it in the tragic experience of the Second World War. In those difficult years, it was a particular support and an inexhaustible source of hope, not only for the people of Krakow, but for the entire nation. This was also my personal experience, which I took with me to the See of Peter and which, in a sense, forms the image of this pontificate.”

In his funeral homily for John Paul, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the late pope’s closest collaborator, summed up his long pontificate in the framework indicated by Pope Pius XII, saying that John Paul “interpreted for us the Paschal Mystery as a mystery of Divine Mercy.”

Given the vast magisterium of John Paul, it is noteworthy that the only quotation from the Holy Father selected by Cardinal Ratzinger for the funeral homily was that “the limit imposed upon evil is ultimately Divine Mercy.” Six years later, Pope Benedict decided to beatify John Paul II precisely on Divine Mercy Sunday, and three years after that, Pope Francis canonized John Paul on Divine Mercy Sunday in 2014.

John Paul once referred to the Great Jubilee 2000 as the “hermeneutic” of his pontificate, the “interpretative standard” by which to understand his mission. If the jubilee was the hermeneutic, and Divine Mercy was the image, then the Jubilee of Mercy of Pope Francis brings together both in a beautiful gift to the Church, something that the Holy Father will himself highlight in Krakow next summer, when he visits the Shrine of Divine Mercy and the sanctuary of St. John Paul.

is editor in chief of Convivium magazine.

He has been appointed to serve as a

Jubilee Year Missionary of Mercy by the

Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization.

- Keywords:

- dives in misericordia

- divine mercy

- father raymond j. de souza

- pope francis

- pope pius xii

- sacred heart

- second vatican council

- st. john paul ii

- st. john xxiii

- year of mercy