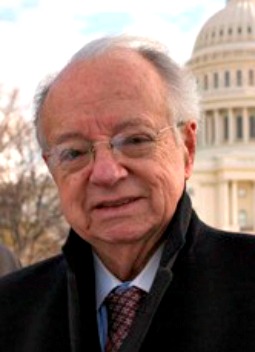

Thomas Melady Transcended Partisan Polarization

NEWS ANALYSIS: The U.S. ambassador to the Holy See from 1989-1993, Melady, who died Jan. 6 at the age of 86, pressed for full diplomatic relations between the Vatican and Israel and queried John Paul II about Gorbachev’s intentions.

WASHINGTON — Thomas Melady, a U.S. ambassador under three presidents and an educator and author who remained active until the end of his life, transcended party politics that have increasingly defined the nation’s capital.

An “old school” diplomat and a member of the Order of Malta who frequently served as a go-between for U.S. Church leaders and Washington policymakers, Melady died of brain cancer at home Jan. 6.

A “man of dialogue,” he is credited with helping to lay the foundations for full diplomatic relations between the Holy See and the state of Israel and served as an emissary between President George H.W. Bush and Pope John Paul II during the waning days of the Cold War, when Washington looked to the Vatican for insight on the goals of the reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

“He was more than a diplomat who served as a U.S. ambassador,” Cardinal Donald Wuerl of Washington told the Register.

“He was a person who was convinced that there was a way to make things better. He spent his time working to bring people together, and always with the goal for a more peaceful world,” added Cardinal Wuerl, who knew Melady for 40 years and presided at his funeral mMass Jan. 13 at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle.

Melady served as the U.S. ambassador to the African country of Burundi in 1969 and later was appointed ambassador to Uganda in 1972. He was an authority on sub-Sahara Africa and wrote 17 books.

Vatican Ambassador

From 1976 to 1986, Melady served as the president of Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Conn., and then assumed the role of diplomat in 1989, when President Bush appointed him as the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See.

Melady and his wife, Margaret, who is also an academic and consultant on educational issues and co-authored several books with him, moved to Rome during the pontificate of Blessed John Paul II, months before the Berlin Wall would come crashing down.

During a Jan. 22 interview with the Register, Margaret Melady recalled her husband’s role during Gorbachev’s historic 1989 visit to the Vatican.

“Gorbachev was going to meet President Bush for the first time, and he stopped to meet the Pope first,” she said.

“President Bush wanted Tom to ask the Pope if Gorbachev could be trusted. When Tom asked him, the Pope didn’t say Yes or No,” Margaret Melady said. “But Tom interpreted the way he answered the question to mean, ‘I think you can deal with this guy.’ He passed that on in a report to the president.”

During that period, many Soviet satellite nations were eager for freedom and looked to the Polish Pope for inspiration. But the White House feared that the pace of change might undermine Gorbachev’s standing at home, and Melady met with John Paul II to share those concerns.

“Lithuania was pressing to be free of the Soviet Union,” Margaret Melady remembered, but the Pope told Lithuanian reformers, ‘Be patient; be patient.’ One year later, Lithuania was free.”

The Holy See and Israel

During his tenure at the Vatican, the Bush administration assigned Melady another delicate mission: the establishment of full diplomatic relations between the Holy See and Israel.

“Tom began to work on it in a very quiet way. He asked some U.S. cardinals to help him communicate this to the Vatican,” Margaret said.

To advance the mission, the Meladys “went off, incognito, to Israel with an Italian pilgrimage to meet secretly with Israeli officials and Christian leaders. It took a long time, but it finally happened, just after he left the Vatican,” she recalled.

In 1993, full diplomatic relations were established with the adoption of the Fundamental Accord by the two states that addressed tax exemptions and property rights of the Roman Catholic Church within the territory controlled by Israeli.

“The work of the recognition of Israel and its relations with the Holy See was a milestone,” said Ken Hackett, President Barack Obama’s newly appointed ambassador to the Holy See, during a telephone interview with the Register. “The elements of that are still being played out on the work of the Fundamental Agreement between the Holy See and Israel; it is not concluded yet. But during Tom’s time, the foundation was laid, and that was terrific.”

“The effectiveness of Tom Melady was enhanced by his prior experience as an ambassador in Central Africa and as a university president,” Hackett noted. “He was able to move between the different interests of the Church internationally and he offered something special.”

Prudent Counsel

Thomas Patrick Melady was born in Connecticut to working class parents and was the first in his family to earn a college degree; he later obtained a doctorate from The Catholic University of America. Throughout his life, he served as a mentor, advising the young Africans he met during the 1960s, as African independence movements gained traction, and counseling the graduate students he taught during his recent tenure as senior diplomat in residence at the Institute for World Politics in Washington.

“He made a significant contribution, not only teaching, but going out of his way to mentor both students and interns,” said John Lenczowski, the founder and president of the Institute for World Politics, an independent graduate school of national security and international affairs.

Those who succeeded Melady as U.S. ambassadors to the Holy See also benefited from his prudent counsel, whether they served in Republican or Democratic administrations.

“Immediately after the 1992 U.S. presidential election, when my name began to surface as a possible candidate for U.S. ambassador to the Vatican, I received a telephone call from Tom Melady, who was then serving in that role,” Ray Flynn, the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See during the Clinton administration and a former mayor of Boston, told the Register.

“He asked if I would be willing to meet with him in Boston to talk to me about my future plans. When we met, he told about the work he was doing on behalf of President Bush to encourage diplomatic relations for the first time between the state of Israel and the Holy See,” said Flynn, who was inspired by Melady’s efforts to advance the delicate negotiations.

Flynn became Melady’s successor and sought to complete that critical mission.

“As soon as I arrived in Rome, my first two stops were to visit the ambassador from Israel and the cardinal secretary of state and express the support of the president for the historic diplomatic relationship between the two governments,” said Flynn.

Working for Common Good

He also recalled that Melady advised him on the art of diplomacy and the need to tamp down his public persona if he accepted an appointment to the Vatican.

“He told me, ‘Being mayor, you do little things and seek a lot publicity. Being a diplomat, however, you might accomplish a big thing, but you don’t talk to the press to take any credit. You remain silent,’” Flynn recalled. “A very important piece of advice.”

Cardinal Wuerl acknowledged Melady’s striking unselfishness and willingness to work behind the scenes for the common good.

“He felt that the protocols that exist in life are a way to show good manners and to be respectful of people, and it didn’t matter what political party you belonged to.”

In recent years, Melady led a campaign to promote civility among Catholics, amid an often rancorous debate over social and economic policy. He also joined past U.S. ambassadors to the Holy See to criticize the Obama administration’s decision to move the U.S. mission at the Vatican to the complex that housed the U.S. Embassy to Italy.

Meanwhile, he maintained steady contact with the Holy See’s embassy in Washington,

“He tended to accord immediate respect to the Holy See’s views on various policy issues, including its reluctance to support U.S. military intervention in Iraq and Syria — especially since that reluctance was based, among other things, on concern for the welfare of the Christian populations of both countries,” noted John Lenczowski.

“Indeed, the Vatican’s fears about the consequences of the Iraq invasion have been vindicated by the course of events there.”

Joan Frawley Desmond is the Register's senior editor.