This Lent: A Call to Reconcile Black and White Starts in Birmingham

An important conference begins March 3 in Alabama that will take up the unfinished work of the civil-rights movement: racial reconciliation, under the common fatherhood of God.

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — The city of Birmingham is known as one of the major epicenters of the civil-rights movement, where religious leaders, most notably Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., challenged the conscience of a nation.

But this week, the city of Birmingham is bringing civil and religious leaders together for another much-needed national project that may well be described as the unfinished work of the civil-rights movement: reconciling black and white Americans.

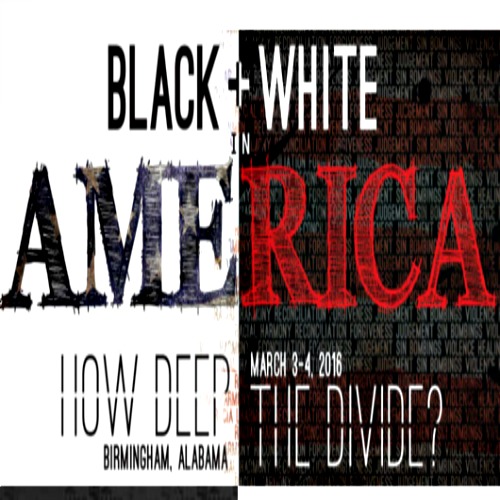

Bishop Robert Baker of the Catholic Diocese of Birmingham, Dean Timothy George of Samford University’s Beeson Divinity School and Birmingham Mayor William Bell have joined together to host a national conference on racial reconciliation at Samford called “Black and White in America: How Deep the Divide?” March 3-4.

In this interview with the Register, Bishop Baker explains that the United States is overdue for an honest national dialogue about the persisting racial divide between black and white, so that religious and civil leaders can find the path to move forward on reconciliation, healing and achieving true racial harmony.

Bishop Baker, why do you feel it necessary to raise this discussion about racial reconciliation? What makes this conference in Birmingham so important?

I think Americans have long prided themselves on the great strides that have been made already on race relations, since the emergence of the civil-rights movement back 50 years ago. In Birmingham and elsewhere, we felt we have come a long way. But then, there appeared those race riots and protests in Ferguson, Mo., Baltimore, Los Angeles, Oakland [Calif.] and Brooklyn. The [University of Missouri’s] president stepped down after a firestorm of accusations against him by members of the football team thinking that he had not acted quickly enough to resolve racial conflict there. So it was clear that the race issue has not been totally resolved, and that reality had to be embraced and discussed.

In this symposium, there’s an effort trying to get leaders from both civil and religious communities to discuss how deep the divide is between blacks and whites and who among us is doing anything positive in bridging that divide.

Birmingham, in many senses, is “ground zero” of the civil-rights movement. Why have this symposium now?

This being the season of Lent, it seems an ideal time to invite God to work on us and take steps towards reconciliation.

What the three of us organizers — Mayor William Bell, Dean Timothy George and myself — seem to recognize with this was that the Church and our society were missing opportunities with diverse cultural groups to speak respectfully to one another.

There are pockets of that going on in the Church and society here in Birmingham: Father Mitch Pacwa [of EWTN] meets with white and African-American leaders at their Monday meetings — and he will be at the conference, but not one of the speakers — and he has been engaged in that dialogue. They have done some positive things ecumenically, black and white together, but I think, unfortunately, it is all too rare.

Our hope is for something that would be an encouragement and a model for others. There are influential leaders in our Church and society that have made a difference, and we have identified some of them, who have made a difference and will be at the conference.

Who are some of the leaders that will be there?

There’s Bishop [Edward] Braxton [of the Diocese of Belleville, Ill.], who rightly points out some of the lacunae, the spots that are missing, so far in the dialogue. He is critical in this discussion, because he has pointed out some areas, where the black community feels that there has been neglect on the part of the white communities.

We have identified Mayor [Joseph] Riley from Charleston [S.C.], who is one of the great mayors of the country. I know because I was bishop there. … He is key to this conference too, because he led Charleston through that terrible crisis when the nine people were murdered.

He is going to help formulate some of the things leaders can work on to help build bridges. He’s a white mayor, who has been elected to 10 four-year terms, and is supported by the black community. I know that he has important things to say, because he led the march as a white man from Charleston to Columbia in 2000 to get the Confederate flag removed from the [South Carolina] Capitol. He has done things as a native Southerner that have been laudatory as a civil leader to build bridges, and he saw the need to do so.

And our mayor, Mayor Bell, who is black, has tried to reach out to the community and build bridges, and he’s one of the leaders of this conference.

Do you have other viewpoints as well, such as law enforcement?

We have also the people who represent the law enforcement in the forum. So we have the state attorney general for Alabama, Luther Strange, who will be responding to the first talks by Mayor Bell and Mayor Riley. I mean, obviously, we have to keep law and order in the state of Alabama, so the law-enforcement perspective will be represented. On the panel, there is also Birmingham’s chief of police, A.C. Roper, so we don’t have a one-sided discussion.

But this is an attempt to listen to all the factors that are involved on both sides of the discussion. I think that’s part of the beauty of what we’re trying to do, which is present the issues squarely and fairly and then move toward a panel discussion.

Besides addressing the racial divide in society, have you seen a racial divide in the Church?

I have an Office for Black Catholics, and I would say that, in my own backyard, I’ve realized my own weakness and need to understand better the black community and to better relate to it. But I try I go to Martin Luther King Day celebrations here, which are massive, and even in our Church here in the diocese we have our Martin Luther King event. We are promoting ways to build bridges, but do I see a divide? Yes, I do. And what Mayor Bell is going to do is spell out, from his vantage point, what Birmingham is: where it was 50 years ago and where it is today. There has been a lot of progress: There’s a working relationship between blacks and whites here, but how amicable things have been is another story.

How do we achieve racial reconciliation?

We have [Catholic] Archbishop Anthony Obinna coming from Nigeria, and he actually has the last presentation. He is of Igbo heritage — many of the slaves of South Carolina and Georgia where of Igbo heritage. … Archbishop Obinna was very grieved over the reality of slavery, which he studied when he was here in the United States in the ’70s. He developed a direction toward a resolution, which he calls “reconfiliation” — not reconciliation, but reconfiliation — and that basically says: We are all sons and daughters of the Father who is God, and then, ultimately, there is a need for rebuilding that filiation.

He actually had a service of reconfiliation when I was bishop in Charleston, and it was to re-establish that filiation, which was ruptured by slavery, because the people who had slaves in our country were not acknowledging the commonality of fatherhood.

So there’s a midday prayer that is led by him, and the homily will be preached by Dean George in their chapel [on campus]. But the ultimate answer comes to the religious standpoint: re-establishing ourselves under that one fatherhood of God.

Thank you so much for giving us a preview of this conference, Bishop Baker. Any final thought for our readers?

The question we’re asking is: What are the characteristics of leaders in society who can bridge the gap of the racial divide that seems to exist? We think the answer is twofold: helping form good leaders, because where there are good leaders, the divide will not happen. So this is oriented principally in helping build leadership in our communities.

But I think we all need to know a lot more about what it takes, because we don’t want to see more Ferguson situations. We’re thinking that if we can set some models for people to pick up, then we can avoid a lot of that in the future. But it will take a lot of time and a lot of effort.

Peter Jesserer Smith is a Register staff reporter.