St. Paul Cathedral Celebrates 100 Years as a ‘Monument of Christian Faith and Love’

On April 12, Archbishop John Nienstedt honored the determination of a predecessor that resulted in a spiritual and architectural landmark.

On the Second Sunday of Easter, two archbishops stood under the same sanctuary dome in the Cathedral of St. Paul in St. Paul, Minn., separated by a century but mystically united in the sacrifice of the Mass.

In his homily at the April 12 liturgy commemorating the centennial of the cathedral’s dedication, current St. Paul and Minneapolis Archbishop John Nienstedt honored the determination of his predecessor, Archbishop John Ireland, who, though not the main celebrant of a Mass 100 years earlier on April 11, 1915, blessed the interior and exterior of the church he had brought to fruition before the Mass — a cathedral that is still one of the largest in the country.

“The excitement and joy that filled the minds and hearts of the apostles and Mary, who had seen the risen Lord on the first Easter night, was again captured by this local Church led by such a determined visionary as Archbishop Ireland in his solemn blessing this day 100 years ago,” Archbishop Nienstedt said. “And so it comes to this moment of commemoration in which we too can be renewed in the faith of our forefathers, faith that is rooted in … Jesus and a faith that is blessed and imprinted into the very walls of this cathedral.”

The congregation at the 1915 dedication Mass saw only the unfinished sanctuary of their new cathedral, not the elaborate brass baldachin supported by black marble columns that now arches over the altar.

Nor did they see the 21st-century parish’s dedication to the faith and to the same cathedral they had financed with hundreds of often small, sacrificial contributions.

But they might have anticipated that their cathedral — the archdiocesan co-cathedral designated as the National Shrine of the Apostle Paul in 2009 by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Vatican — would be a destination not only for Catholics but people of many faiths, nationalities and walks of life.

Two weeks before the 1915 dedication, 18,000 attended the cathedral’s first four Masses on Palm Sunday and were awed by the massive building, said cathedral archivist Celeste Raspanti, who has been a parishioner since 1981. Hoping to compensate for acoustic limitations with his commanding voice, Archbishop Ireland preached:

“The cathedral was built by the Catholics of the Diocese of St. Paul as the supreme monument of their Christian faith and their Christian love,” he said. “Therefore, today it is beautiful; it is noble. Therefore, tomorrow, it will be still more beautiful, still more noble.”

Picture Book of Faith

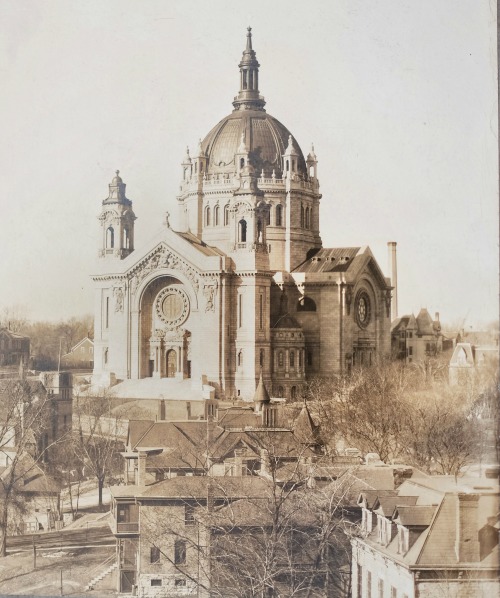

French architect Emmanuel Louis Masqueray designed the modified Renaissance-styled cathedral whose nearly-equal sized arms resembled a Greek cross. The exterior was built between 1906-1914 — in large part with regional materials — at a cost of $1.69 million.

More than 300 feet tall at the top of the cross on its main dome and seating more than 3,000, the church maintains a commanding presence on a hill near downtown St. Paul.

“It’s an enormous space,” said St. Paul-based architectural historian Larry Millett. “It’s got the kind of finishing with all of the glass and sculpture and that sort of thing that we don’t do anymore and we never will do again.”

The cathedral was built during a national construction boom when at least 20 others were planned. Its construction is more remarkable because Archbishop Ireland at the same time commissioned a Masqueray-designed co-cathedral in Minneapolis, the Basilica of St. Mary, completed in 1914.

Archbishop Ireland and Masqueray died before seeing the cathedral’s interior finished with marble, gold and stained glass — work that was nearly completed at the time of the cathedral’s formal consecration in 1958.

Not just beautiful, the interior illustrates the faith, Raspanti said. “Like a medieval cathedral, this church is a picture book,” she said. “All you have to do is look at the things [in it], and you learn about” the faith.

Archbishop Ireland would probably approve of the cathedral, while also noticing important work now needed, such as re-leading of the rose windows, said Father John Ubel, the cathedral’s rector.

A Parish, Not a Museum

The cathedral’s original red oak pews have side panels carved into curving waves that relate to the symbolic boat of St. Peter, the refuge of Christians. Of the thousands of parishioners who have sat in the pews, 800 families are current members.

Parishes exist for the spiritual life of the people, Father Ubel said. “I do not want this church to become a museum.”

On April 12, 2015, evidence the cathedral is more parish than museum included Easter flowers, a large image of Divine Mercy and numerous small boys in sport coats. With a brunch after Mass, the parish continued its yearlong centennial celebration that includes events and monthly service projects.

Mary Sweeney, who, with her husband, Patrick, has been a cathedral parishioner for nearly 50 years, commented, “The church just makes you feel good when you go in there. It feels like home.”

Patrick, who assisted with cathedral maintenance for 38 years, marveled at the building’s workmanship, referencing “the way they cut the marble back then, when they didn’t have the tools like they have now. I think the carpentry work is just amazing. It would be difficult to match it today.”

Behind the sanctuary, the Shrine of the Nations has six altars featuring saints from the home countries of many who settled in the Twin Cities. Through the shrine, Archbishop Ireland convinced the ethnic groups to invest in the cathedral, evidence of his broader vision for it.

“I think, so often, we tend to think of these things as belonging to the Church, and people probably too often think of that as the institution,” Father Ubel said. “It’s all together, but, ultimately, it is the work of the people.”

The cathedral continues to draw the faithful, along with non-Catholic visitors. “It’s an important cultural monument as well as a religious monument in the city,” Millett said. “It’s part of the fabric of the city now, and it’s hard to think of St. Paul without it.”

Eucharistic Focus

From the cathedral’s main doors, one’s eye looks to the sanctuary, Raspanti said. “There’s no doubt about what’s important in the church; and, of course, in the Catholic Church, the important thing is what’s in the sanctuary: the Eucharist.”

Frequent cathedral Mass attendee Christopher Engelmann agreed: “This entire building is built on the foundation of something very, very small: the Blessed Sacrament of the holy Eucharist. I sense that.”

Halfway up the main aisle, many stop to look up at the cathedral’s main dome, into which the Statue of Liberty could fit without her pedestal, Raspanti said. Illuminated by stained-glass windows depicting the angelic orders, the dome is a reminder of our heavenly destination.

While preparing for heaven, cathedral usher Don Fuller appreciates his earthly spiritual home. After leaving because of anger at the clergy sex-abuse scandal, he returned to the cathedral two years ago. Now, he admires it, along with those who sacrificed and waited years for its completion.

“Before I come in, I sit and pray that I can approach the cathedral with the joy and reverence the original parish had,” he said. “Look at what they gave: It was 10 years of giving and 10 years of waiting.”

Susan Klemond writes from St. Paul, Minnesota.

- Keywords:

- archbishop john ireland

- archbishop john nienstedt

- church architecture

- st. paul, minnesota

- susan klemond