Sanctity in the USA: Priest, Religious and Laywoman Being Considered for Sainthood

Venerable James Miller, Servant of God Edward Flanagan and Servant of God Julia Greeley served Christ well in their vocations.

The Communion of Saints consists of individuals from all walks of life who, within their particular vocations — whether as priests, consecrated religious or laypersons — are called by God to holiness.

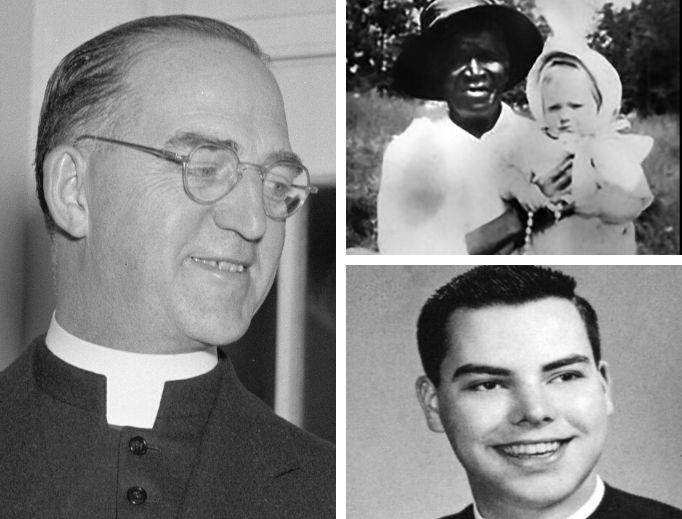

Those individuals in the U.S. who are currently being considered for sainthood reflect that same diversity of vocations, including Venerable James Miller, a De La Salle Christian Brother; Servant of God Edward Flanagan, a diocesan priest; and Servant of God Julia Greeley, a laywoman.

A Wisconsin native, Brother James Miller will be beatified on Dec. 7. Recognized as a martyr for the faith by Pope Francis in 2018 (which set the path to beatification), Brother James was murdered by gunmen in Guatemala. His cause was first opened in 2009 in the Diocese of Huehuetenango, Guatemala, where he was serving at the time of his death, and faithful in Wisconsin and the Christian Brothers are also promoting his cause.

Also being considered is the cause of a well-known priest of the Archdiocese of Omaha, Nebraska, who had achieved celebrity status in the U.S. before his death. Father Edward Flanagan is the founder of Boys Town for homeless boys. His cause was opened in 2012. The Father Flanagan League is helping to advance his cause in Omaha.

A laywoman in the U.S. is also being considered for beatification: Julia Greeley, a freed African American slave whose devotion to God and dedication to Denver’s poor led the Archdiocese of Denver to open her cause in 2016. Her cause is being supported throughout the Denver area and especially by the Julia Greeley Guild.

Since their causes have been officially recognized by Rome, Father Flanagan and Greeley are now named “Servants of God.”

Brother James Miller

Brother James Miller was the first De La Salle Christian Brother from the U.S. to be beatified. He was killed in the afternoon of Feb. 13, 1982, while fixing a wall at the De La Salle Indian School at Huehuetenango, where he was stationed as part of his work in helping Guatemalans through education and employment opportunities. Shortly before his death, three hooded men approached Brother James while he was standing on a ladder and shot him multiple times. He died instantly. The men were believed to be members of a local crime syndicate, although there is also speculation that they may have been part of a government-sponsored “hit squad” seeking retribution against the Christian Brothers for intervening on behalf of students that the Guatemalan military sought to conscript.

Brother James was born on Sept. 21, 1944, in Stevens Point, in the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin, and attended high school at Pacelli High School there. He is buried in the diocese in Ellis, Wisconsin.

Father Thomas Lindner, a priest of the Diocese of La Crosse and pastor of St. Anne parish in Wausau, has been closely involved with efforts to keep Brother James’ memory alive in the Stevens Point area, including until recently an annual Brother James Miller Day in the diocese.

“I would like to think that those of us who contributed effort and attention to that commemoration [Brother James Miller Day] have helped to maintain interest in and dedication to Brother James’ cause,” Father Lindner said, adding that he hopes the renewed focus on Brother James’ life, since it was announced he would be beatified this upcoming December, will spark the community to re-engage in a similar commemorative day “maybe in connection with his feast day.”

Other signs abound that Brother James remains a vital part of his native Wisconsin community.

“What’s most compelling, in terms of Brother James and central Wisconsin, is the direct link,” Father Lindner said. “We all know people who knew him. His siblings still live in the area and have always been part of the tradition of honoring his legacy. His brothers still farm where he grew up.”

While Wisconsinites claim the religious brother as one of their own, Father Lindner said that it is appropriate that his cause should be opened in the Guatemalan diocese and among the people he served at the time of his martyrdom.

“The people of that Christian community knew of his ministry, his witness and his sacrifice firsthand,” Father Lindner said. “I would suspect that their honoring the story and legacy of Brother James was far more intimate and intense than it would have been elsewhere.”

Brother James’ life serves as a witness to the fact that being Christian requires more than lip service, Father Lindner said.

Brother James, he said, “could have played it safe and come home, knowing the dangers lurking in Guatemala plagued by civil war, but he didn’t. It’s tempting for followers of Jesus in any time and place to play it safe, as well. The witness of Brother James will hopefully call us beyond that inclination. And I would hope that his ministry among oppressed people in Guatemala confronting considerable injustice might compel us to honor Blessed James by confronting injustice in our day and seek his intercession in that pursuit.”

Father Edward Flanagan

Father Edward Flanagan was born in Ireland on July 13, 1886, and emigrated to the U.S. in 1904. Five years after being ordained a priest for the Diocese of Omaha in 1912, Father Flanagan opened his first home for boys, the seed for what was eventually to become Boys Town. In 1921, he moved his outreach to a farm 10 miles west of Omaha and expanded operations until his “City of Little Men” became officially known as Boys Town.

Especially remarkable for the time, Father Flanagan accepted boys into Boys Town of any race or religion, and he especially sought out the hardest cases to invite to the town, work which took him to 31 states in the U.S. and 12 countries around the globe. While visiting in Europe, Father Flanagan died on May 15, 1948, in Berlin.

Father Flanagan’s charity and courage became so renowned that, besides becoming a counselor to world leaders, this priest also caught the attention of Hollywood. In 1938, Boys Town came to movie houses around the country, featuring Spencer Tracy as Father Flanagan, who won an Oscar for his role. The film also won an Oscar for “Best Writing: Original Story” and earned more than $2 million in profits.

Steven Wolf is president of the Father Flanagan League and vice postulator for Father Flanagan’s cause. He told the Register that the people of Omaha urged the archdiocese — and at the time Archbishop George Lucas — to open the priest’s cause, so great was the love for this priest and his work with young men. It is a love that remains unflagging today.

“There is a formal weekly intercessional prayer gathering at Servant of God Flanagan’s tomb that has been continuous since 2001, and people are praying daily at his tomb,” Wolf said, adding, “More than 3,000 people have been on pilgrimage with the league to walk in Servant of God Flanagan’s footsteps at Boys Town.”

Father Flanagan’s life also serves to counter negative headlines that the priesthood has earned in the wake of the Church’s sexual-abuse scandal.

“In light of the global scandal of clergy abusing children, Servant of God Flanagan is an icon, a beacon and role model of applying the Gospel and the sacrament of holy orders to protect, help, nurture and lovingly care for vulnerable children,” Wolf said.

According to Wolf, Father Flanagan cared for the children of God as if they were God himself in need.

“He did this around the globe,” Wolf said, “and literally gave his last breath while on a mission trip to Germany at the request of President Harry Truman to help the war-torn orphans of World War II in Austria and Germany, passing away in Berlin.”

Especially in his treatment of minorities, Wolf said, Father Flanagan “was decades ahead of the U.S. civil-rights movement by taking in children of every race, creed and color, without discrimination of any sort. He was mocked and scorned for all of this, and even experienced death threats from the Ku Klux Klan for taking in all these ethnically diverse children.”

In a culture that has devalued fatherhood, Wolf said, Father Flanagan’s example is as vital as ever for the Church — and the world.

“In terms of relevance, Servant of God Flanagan remains highly relevant and modern in the continuing global need for the loving care of disadvantaged, abused and neglected youth,” he said. “Our culture is growing harder and coarser toward children, so many of them coming from broken and single-parent homes.”

Julia Greeley

Known as “Denver’s Angel of Charity,” Julia Greeley was born a slave in Hannibal, Missouri, sometime between 1833 and 1848 and lost her right eye when her slave master hit her with his whip. After being freed in 1865 as a result of Missouri’s Emancipation Act, Greeley made a living as a household servant in Missouri, Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico before settling down in the Denver area. She soon became well-known in the Mile-High City for her selfless devotion to the poor, begging for food and clothing on their behalf. Like a modern-day St. Nicholas, she often delivered donations at night to prevent those she helped from feeling embarrassed or beholden to her.

In 1880, Greeley converted to Catholicism and became well-known for her devotion to the Sacred Heart. In 1901, already deep into her faith as a daily communicant, Greeley became a Secular Order Franciscan and remained a steady champion of the poor until her death in 1918. Hundreds of mourners visited her casket during the wake at her parish.

David Uebbing, chancellor for the Archdiocese of Denver and vice postulator for Greeley’s cause, said that devotion to Greeley as a model of sanctity has thrived in the century since her death. He has no doubt that Greeley remains alive in the hearts of all those who have heard her story, especially given the number of daily visits to her tomb — and a recent pilgrimage of faithful from St. Louis to her resting place.

“The number of people learning about Julia Greeley,” he said, “and asking for her intercession has grown steadily.”

As an African American, Greeley was a witness twice over to the love of Christ, Uebbing said, noting that she “is relevant today because she firmly believed that every person was loved by God, regardless of their color or station in life.”

As with all saints, Greeley made sure that she wasted neither her time nor her efforts in bringing Christ to others, he added.

“We live in a culture that Pope Francis has called a ‘throwaway culture,’” Uebbing said, “and Julia, who had an eye that was disfigured by a whip and walked with a limp was a woman who steadfastly believed that every person was loved by Jesus.”

But her lamed eyesight wasn’t the only cross that Greeley carried with joy, he added.

“One of the things that the exhumation of Julia’s remains revealed was that she had arthritis in nearly every joint of her body and that her right knee had no cartilage in it,” he said. “Yet every First Friday, Julia would walk on foot to the 20 fire stations of Denver and hand out Sacred Heart League pamphlets to the firemen, Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Obviously, she was incredibly strong and perseverant. Her faith and care for the souls of the firemen drove her to hand out these pamphlets, which she called ‘tickets to Heb’n.’ Her perseverance and love for others, especially those in danger like firemen or who were poor, is certainly worthy of imitation.”

Joseph O’Brien writes from Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin.

This story was updated after posting.