Remembering John Paul II’s First US Visit 40 Years Ago

COMMENTARY: Karol Wojtyla’s return to America, this time as pope, had many meaningful moments — and lighter ones.

Pellegrini was among a crowd of 400,000 that greeted Pope John Paul II that Oct. 1, 1979, his first day on U.S. soil as pope, arriving directly from Ireland. It would be the first of seven visits to a country beloved by the Polish pope.

To say that the future saint was greeted like a “rock star” is actually an understatement.

Elvis and the Beatles didn’t get responses like this.

The Pope visited several major cities, where he was greeted by phenomenal crowds, including the throng at a ticker-tape parade in Philadelphia. He celebrated Mass at sites as diverse and expansive as Yankee Stadium, the Washington Mall, Chicago’s Grant Park, and St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington, D.C.

The Mass at Yankee Stadium was packed with 80,000 people. The Grant Park crowd approached a half-million, drawn from the ethnically Polish and Slavic Chicago environs. At Philadelphia’s Logan Circle, the mass reached more than a million.

In Philadelphia on Oct. 3, the Pope spoke at the Cathedral of Sts. Peter and Paul, which made him feel not too far from his home church in Rome, St. John Lateran, which houses the skulls of Sts. Peter and Paul. The parallel was not lost on the Bishop of Rome.

“This cathedral links you to the great apostles of Rome, Peter and Paul,” noted the Pope. He added that he felt home in Philadelphia, where he had visited three years earlier for the Eucharistic Congress amid America’s bicentennial. Back then, he was a relatively unknown cardinal from Krakow. But now, he told the people of Philadelphia, “by the grace of God, I come here as Successor of Peter to bring you a message of love and to strengthen you in your faith.”

Karol Wojtyla’s return to America, this time as pope, had many such meaningful moments — and lighter ones.

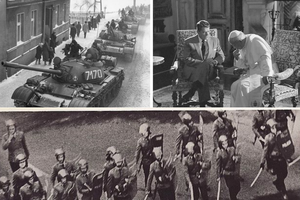

He attended an event with President Jimmy Carter on Oct. 6 on the White House lawn. The Southern Baptist president was gracious and playful with the leader of the Roman Catholic Church.

“You are welcome with us, Your Holiness,” said Carter. Turning to the press and White House staff, Carter said: “As you know, he comes to us as a pastor, as a scholar, as a poet, as a philosopher, but I think primarily as a pastor.” He then turned to the Pope and quipped, “Do you agree? As a pastor?”

The Chief Pastor of the universal Church smiled and said, “You are right.”

It was a fun moment, and everyone took it in stride.

But surely the most serious of John Paul II’s moments during his inaugural trip to America was his speech to the United Nations, only the second papal appearance before the stately body, behind only Paul VI, and ultimately the first of two U.N. stops by the Holy Father during his long papacy. It came early in his visit, on Oct. 2. It was a striking oration in length alone, requiring a full hour to deliver.

The Pope told the assembled delegates that he was taking advantage of this major opportunity to send his greetings to literally “all the men and women living on this planet,” to “every man and every woman, without any exception whatever.” This was a sweeping ambition, to be sure, but it was nonetheless doable (at least symbolically) in this unique forum.

The Pope told them:

“Each one of you, distinguished ladies and gentlemen, represents a particular state, system and political structure, but what you represent above all are individual human beings; you are all representatives of men and women … each of them a subject endowed with dignity as a human person.”

Those were words that this international body badly needed to hear.

John Paul then hit upon one of the worst recent violations of that dignity. He recalled that the world had just marked the grim anniversary of the September 1939 invasion of Poland and the start of World War II four decades earlier. It was a picture, said the Polish Pope, that “I still have before my mind.”

Speaking of some of the consequences of that invasion, he brought up Auschwitz: “This infamous place is unfortunately only one of the many scattered over the continent of Europe.”

He condemned any and all past and present examples of such repression — “everything that is a continuation of those experiences under different forms, namely the various kinds of torture and oppression, either physical or moral, carried out under any system, in any land.”

This was surely a reference to Soviet communism and its repression and camps in the gulag archipelago. The Pope’s advisers knew that it was. The Soviets, who reportedly were unhappy with the remarks, also knew of whom the Pope was speaking. How could they not? They were the embodiment, after all.

“You will forgive me, ladies and gentlemen, for evoking this memory,” John Paul said. “But I would be untrue to the history of this century, I would be dishonest with regard to the great cause of man, which we all wish to serve, if I should keep silent.”

The Pope said that he wanted to also draw attention to “a second systematic threat to man in his inalienable rights in the modern world.” This was the threat posed to religious liberty and conscience. This, too, was a reference to the jackboot of atheistic Soviet communism. And, sadly, it applies prophetically to our 21st-century world today, whether in the secular West or the Islamic Middle East.

And likewise highly relevant still today, the Pope urged the need for “respect for the dignity of the human person.” He smartly noted that the United Nations had proclaimed 1979 the “Year of the Child.” He was now holding them to it, and maybe in a way they didn’t expect or want.

He implored the audience to respect life from its earliest stages with “concern for the child, even before birth, from the first moment of conception and then throughout the years of infancy and youth.” This, he said, was the “primary and fundamental test of the relationship of one human being to another.”

It was a strong speech, no question. It never once used the words “Russia,” “Soviet Union,” “USSR,” “Bolshevism,” “communism” or “Marxism-Leninism.” It clearly, however, dealt with those phantoms. It was subtle but still clear.

Still, even as John Paul II had not eviscerated an “Evil Empire,” what he said had rattled the Kremlin.

For the hypersensitive Soviets, this was interpreted as a vile, belligerent stance of confrontation by the Bishop of Rome. Coming on the heels of John Paul’s historic visit to Poland the previous June, the Soviets were extremely concerned about the actions of this new pope.

They would seek ways to respond, with vengeance. They wanted him stopped. But alas, that’s another story and remembrance for another time.

As for October 1979, Pope John Paul II’s remarkable path through history included a memorable stop here in the United States.

No one could have seen it then, but it was just the start of a pontificate that would run until April 2005, and one that would truly change the course of history.

Americans had never seen or heard anything like it, and probably never will again.

Paul Kengor is a professor of political science at Grove City College in Grove City,

Pennsylvania. His books include A Pope and a President: John Paul II, Ronald Reagan and the Extraordinary Untold Story of the 20th Century.

- Keywords:

- paul kengor

- pope st. john paul ii