Of Silence and Stone in the Cloister: Fairfield Carmelites Build New Monastery

Thousands of benefactors have donated to help the sisters dwelling in Pennsylvania.

In 2018, a group of Discalced Carmelite nuns left the Carmel of Jesus, Mary and Joseph in the farmlands of Elysburg, Pennsylvania, and traveled to another region of the Diocese of Harrisburg to found a second monastery in Fairfield, just 8 miles from the historic town of Gettysburg.

Both groups of nuns are originally from a Carmel convent in Valparaiso, Nebraska, and as the order has experienced a surge in vocations, small groups of nuns have branched out to form new communities. The Fairfield Carmelites currently number 11, with most in their 20s and 30s, wear the traditional habit, make use of the extraordinary form of the Mass and Divine Office, and pray for the Church and the world. “We don’t engage in an active apostolate, but live a retired and cloistered life,” said Mother Therese of Merciful Love, the subprioress and novice mistress.

The nuns spend up to six hours per day in formal prayer, and the remainder of the day is spent in silence and personal prayer.

“When we wash dishes, for example, we say prayers for the holy souls in purgatory,” explained Mother Therese. “We try to knit the whole day together in prayer.”

The nuns wear a traditional brown habit made of wool and self-made hemp sandals. They make many sacrifices, including regular fasting and abstaining from meat. They live in an enclosure, surrounded by walls and grills, and use little technology. They use candles for light, handwash their dishes and cook their food on a wood stove.

“We are trying to live our lives in poverty and simplicity, without relying on modern comforts,” Mother Therese said.

And, as the sisters value “hiddenness,” they don’t allow their faces to be photographed.

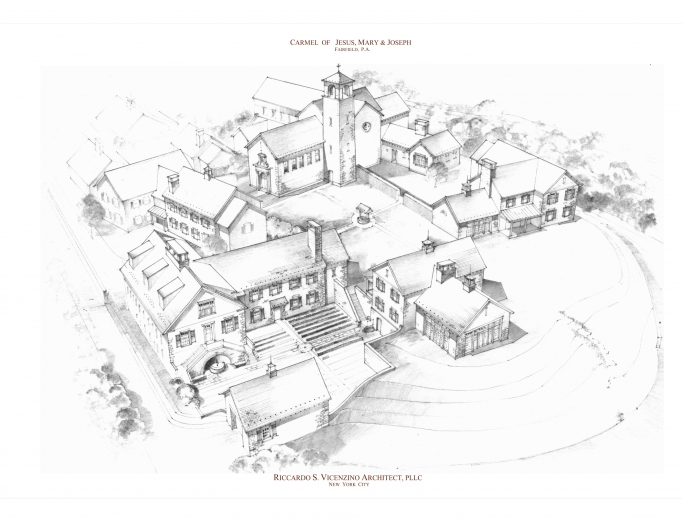

With the help of local construction workers, the nuns are building a new monastery modeled after one envisioned by Carmelite St. Teresa of Ávila (1515-1582) herself, with most of the buildings constructed of stone. The completed monastery will include a dozen buildings and a chapel and may take 25 years or more to build. The total cost is expected to be $12 million, with $4 million already raised. As in Elysburg, the nuns hope to one day to be self-sustaining, operating a small farm with vegetable gardens and livestock at its 40-acre site.

Tom Bauer is general contractor for the project and caretaker of the grounds. He is also Mother Therese’s widowed father. The choice of stone, he explained, is because the sisters want “to build something that will last 1,000 years.” The only buildings on the grounds not to be built of stone, he said, will be the barn and caretaker’s house.

Building the monastery has become a family affair, as Mother Therese’s sister, Catherine Bauer, was recruited to help the sisters with fundraising. “The sisters are adorable. They are lively, joyful and exude a sense of peace and enthusiasm,” she said. “They live a hard and laborious life, but they remain enthusiastic about it.”

Tom Bauer said he knew his oldest daughter had a vocation since age 3. “She’d kiss our statue of the Blessed Mother and was so reverent in her prayers. She wanted to go to Mass all the time,” he recalled.

Catherine is three years Mother Therese’s junior. “When she was younger, she wanted to get married and have 20 children,” Catherine recalled, “but by the time I was 11, she believed she had a strong calling to become a nun.” In 2003, at age 17, the future Mother Therese visited the Carmelite cloistered community in Valparaiso and “knew right away she wanted to enter.”

It was a difficult adjustment for the family to make, both Bauers recall. As Tom said, “It was brutal. We missed seeing her.”

Yet, over time, he conceded, “I could see she is extremely happy. This is her vocation, a job she takes seriously.” In fact, he noted, working around the nuns, he has come to see “they’re all extremely happy.” He recalled one night recently, when the nuns welcomed a new member to their community. From outside the cloister, “I could hear the sisters laughing. They live in such joy and happiness. They eat well, sleep well and are such a joy to be around.”

Tom’s wife also played a key role in helping the Fairfield Carmelites become established, but she succumbed to cancer last fall at age 59. While losing her was devastating, Tom said, living near and working with the nuns has brought him great consolation: “I feel very blessed to be here.”

While the sisters plan to become self-sufficient, at present they rely on the generosity of lay friends. As Tom noted, “They’ve received a lot of support from the community.” Local beekeepers, for example, are donating bees to the sisters and will teach them how to care for them. A sewing teacher is volunteering to teach the sisters sewing and spinning; an organic farmer is donating fruit trees. Thousands of benefactors have donated to help the sisters build their monastery, Catherine said, with the majority of the funds coming from small donors. Raising the needed funds and finding talented stonemasons has been a challenge, she noted, but it has been well worth it, she said, adding, “In this day and age, everything is built so quickly. These Catholic nuns, however, are building like our American forefathers once did, in stone. They want to build a Carmelite monastery that will last.”

Jim Graves writes from

Newport Beach, California.

Online: FairfieldCarmelites.org

- Keywords:

- carmelites

- jim graves

- religious orders