Justice Scalia’s Advice on ‘the Ways of Christ and the Ways of the World’

BOOK PICK: Scalia Speaks

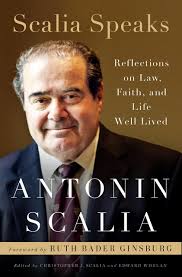

SCALIA SPEAKS: REFLECTIONS ON LAW, FAITH, AND LIFE WELL LIVED

By Antonin Scalia

Edited by Christopher J. Scalia and Edward Whalen

Crown Forum, 2017

421 pages, $30

To order: amazon.com

The U.S. Supreme Court sits in a building on Capitol Hill designed like a Roman temple. A certain approach to civics treats decisions emanating from that American Parthenon like decrees handed down from Olympus, to which Americans bearing true faith to the Constitution must pledge absolute fidelity.

Set against such judicial apotheosis, I found this book quite appealing: The late Antonin Scalia pulls back the curtain to reveal the very human side of one of the “Wizards of First Street.” The man we meet in these pages is profound yet very human, erudite but with the common touch, stylistic but not stuffy. Nino Scalia was somebody I’d like to have had for a neighbor and the stuff of judicial temper.

This book is a wide-ranging collection of 48 of Scalia’s speeches, delivered over the three decades he sat on the court. Their scope spans being American to being a believer, education and the law, virtue and character, and tributes to heroes and friends. The typical speech runs six to eight pages and, given Scalia’s felicity of style, a pleasure to read.

Son Christopher and former law clerk Ed Whalen, the book’s editors, achieved something rare in this sort of anthology: choosing and blending texts so well that the reader can pick up the book and put it down after a single speech (but he’ll want to go back), while the whole collection forms a cohesive whole rather than just a bunch of talks stuck together.

The very human Scalia shows us the Italian kid going to an Irish Jesuit high school in New York; the father who gives good counsel to his kids; the Catholic who takes his faith seriously, knowing “things do not work out the way you want, but the way God wants.”

Scalia’s speeches devote attention to the competing claims of God and Caesar. He recognizes the former’s primacy and, therefore, why there should be something distinctive about the believer:

“It is enormously important for Christians to learn early and remember that lesson of ‘differentness’; to recognize that what is perfectly lawful, and perfectly permissible, for everyone else is not necessarily lawful and permissible for us. The ways of Christ and the ways of the world — even the world of Main Street America — are not the same, and we should not expect them to be. Christ makes some special demands upon us that occasionally require us to be out of step. It is only if one has that sense of differentness — not animosity towards others in any sense, but differentness — that one has a chance of being strong enough to obey the teachings of Christ on many matters much more significant than Friday abstinence and Communion-fast rules — for example, rules of sexual morality.”

At the same time, Scalia also insists a civil judge’s remit is limited. Taking issue with Aquinas, Scalia insists that a civil judge in a constitutionally limited state should stick to the text of the constitutional document and not his reading of equity or even natural law.

America’s abortion license should be limited not because of how Scalia reads the natural law, for example, but simply because there is nothing in the Constitution (apart from what Justice Byron White once called “raw judicial power”) that affords Roe v. Wade a foundation.

The reviewer might not necessarily agree with Scalia’s take on natural law, even though he understands the basis for (and shares) the late justice’s insistence on the original meaning of the Constitution and on hewing to legal text. Any reader who wants to encounter a first-class mind — and a first-class writer — should get this book.

John M. Grondelski, Ph.D., writes from Falls Church, Virginia.

- Keywords:

- john m. grondelski

- justice antonin scalia