Continuing St. Damien and St. Marianne’s Legacy of Mercy

Franciscan Sister Alicia Damien Lau has served the lepers of Molokai on and off, beginning more than 50 years ago.

The Church celebrates the feast day of St. Damien of Molokai (1840-1889) on May 10. St. Damien is known throughout the world for devoting the last 16 years of his life to caring for the lepers confined to the Hawaiian island of Molokai, eventually contracting and succumbing to leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, himself.

Originally from Belgium, Damien de Veuster joined the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary and volunteered for their mission in Hawaii. He was ordained a priest in Honolulu’s Cathedral of Our Lady of Peace in 1864.

He spent nine years working on the island of Hawaii before volunteering to serve the lepers quarantined for life on the Kalaupapa and Kalawao regions on the north side of Molokai. He served the spiritual and physical needs of the people, while maintaining an intense prayer life he believed vital to his success. He was canonized by Pope Benedict in 2009.

Honored alongside Damien is Franciscan Sister Marianne Cope (1838-1918), who left New York with a small group of nuns in the final months of Damien’s life, caring for the dying priest and continuing his work after his death. She was canonized herself in 2012. The pair hold a special place of honor in Hawaii’s Catholic parishes.

A total of 8,000 lepers — or “patients,” as they prefer to be called — were exiled to Molokai 1866-1969. Today, only seven remain by their own choice, ranging in age from their mid-70s to 91 (eight others live on other islands of Hawaii). The seven are served by 40 Department of Health staff members; the National Park Service has maintained Kalaupapa as a historic site since 1986. Religious pilgrims wishing to see the historic Molokai sites related to Sts. Damien and Marianne are welcome, but must fly in through Father Damien Tours.

Franciscan Sister Alicia Damien Lau has served the lepers of Molokai on and off, beginning more than 50 years ago. She is a member of St. Marianne’s community, now called the Sisters of St. Francis of the Neumann Communities, and is one of only a few remaining Catholic religious working on the island. She first came to Molokai in 1965, the year she entered her community, when nearly 200 patients were still under quarantine and forbidden to leave the island.

She spoke with the Register about life on Molokai and the legacy of Sts. Damien and Marianne.

What was Molokai like in 1965?

We had a convent with six sisters, five of whom were involved in caring for the patients. During my first visit to the community, I remember the patients coming with guitars and sitting on the steps of the convent and singing to us. This was in keeping with the wishes of Mother Marianne, who wanted Kalaupapa to be a joyful place. She encouraged the patients to make music and dance the hula.

But there were many things that were painful to them. For example, I remember that there were no children. Any who were born were taken away to live with family members or in orphanages, to keep them from contracting Hansen’s disease [leprosy]. Sometimes mothers would give birth but not report it to the authorities for a day, so they could have some time with their children.

There were a lot of pets on the island, particularly dogs. I think the pets were their substitutes for children.

Were they disfigured by leprosy?

Some were, but not as badly as the people you see in the old photos of Molokai. What I saw, mostly, were people with missing fingers or toes.

Were there guards on the island to make sure the patients stayed?

Yes, at one time, but no one would fly them out if they knew they were patients. Even though there were drugs that successfully treated Hansen’s disease in the 1940s, the Board of Health was still concerned that the patients might spread it. They were finally allowed to leave in 1969, and after that, the number of patients on Molokai started decreasing.

Is the Church still active on Molokai?

Yes. We have a full-time priest, Father Patrick Kililea, who is in Father Damien’s community. The Sacred Hearts plan to keep a priest on the island as long as possible. We have a convent with a sister who maintains the grounds, including Mother Marianne’s gravesite. Even though Mother’s remains have been relocated to the Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of Peace in Honolulu, she suffered from osteoporosis, and pieces of her bones can be found in her original gravesite on Molokai.

I come from Honolulu every other week to help the sister at Kalaupapa to maintain the grounds, work in our bookstore and help with patient requests.

Who comes today to Molokai?

No one can come on their own. They must be sponsored. They can be guests of patients or staff, volunteers, tourists or participants in church groups. About 10,000 visit annually, about 9,000 of whom come through Damien Tours. They land at our airport and then can come into Kalaupapa on foot, mule or air by flying via Makani Kai Air. Kalaupapa can only accommodate small planes. Boats from the outside are not allowed to come to the island.

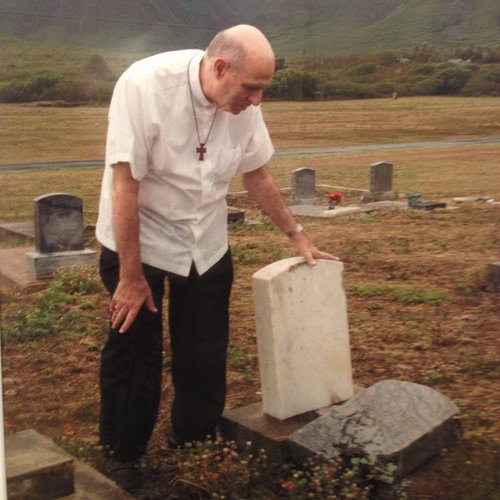

Four times a year, our diocesan bishop, Larry Silva, leads a pilgrimage to Molokai. He has a personal connection; he had a family member who was a patient there. The Diocese of Honolulu has created an official pilgrimage guide, which takes pilgrims to significant sites on Molokai, with suggested prayers and meditations and history of the sites. They include the St. Philomena Church, where Father Damien celebrated Mass and [the site of] St. Damien’s original gravesite. His body was relocated to Belgium, but a relic of his right hand is in the original gravesite.

The diocese supplies the guide to pilgrims or it is available at Molokai’s St. Francis Church.

Honolulu also has some important sites related to Sts. Damien and Mariannne.

Yes. Honolulu’s cathedral houses relics of Damien and Marianne. We are also raising funds to build a Damien and Marianne museum at St. Augustine Church in Waikiki.

When you greet Molokai visitors, what do you tell them about Sts. Damien and Marianne?

That they were ordinary people who did extraordinary works of mercy. They cared for the patients’ bodies while nurturing their souls. They offered unconditional love and compassion. Many of our patients see Damien as their spiritual father and Marianne as their spiritual mother.

I was privileged to attend the canonization of both in Rome. I went with 11 patients to Damien’s canonization and nine to Marianne’s. Most were in wheelchairs. It was an amazing thing to witness.

When will your work at Kalaupapa end?

It will end when the last patient leaves or dies. Six of our seven remaining patients are Catholic and need our support. It is my way of continuing in the footsteps of Father Damien and Mother Marianne.

Register correspondent Jim Graves writes from Newport Beach, California.