Only God Can Make a Tree

The tree’s good fruit is its beauty — being what it should be, just like us, is God’s Glory.

“The mustard seeds springs up and becomes the largest of plants, and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the sky can dwell in its shade.” (Mark 4:31-32)

The readings for the Eleventh Sunday of Ordinary Time (June 17) say a lot about trees. In the first reading, from Ezekiel, God speaks about taking a shoot from the cedar of Lebanon and planting it, raising it into a majestic cedar of its own, in which the birds of the air would dwell. God speaks of making some trees fruitful and some barren as signs of His power (an allusion to the curse of the fig tree in Mark 11:13-14). Today’s Gospel, which picks up the Markan parable of the sower, also speaks of the mustard tree, “one of the smallest of seeds,” which produces one of the greatest of plants.

In the Gospels, Jesus talks a lot about trees. He compares people to trees: you know what kind of tree it is by the fruit it produces (Matthew 7:15-20; 12:33; Luke 6:44). The orchard owner has a right to expect good fruit and if, despite his labors, a tree remains barren, it deserves to stop taking up space and be cut down (Luke 13:6-9). By watching the signs of trees, you can know the times: “"Now learn this lesson from the fig tree: As soon as its twigs get tender and its leaves come out, you know that summer is near” (Mark 13:28). And, while the fall of mankind began with a tree (Genesis 3:1-7), so also its redemption was accomplished on a new tree of life (see Acts 5:30).

It’s fitting we read the passage of the mustard tree and the birds nesting in its branches at the beginning of this summer, because July 2018 marks the centennial of the death of Joyce Kilmer, the American Catholic poet. Kilmer, who is most known for his poem “Trees” (“I think that I shall never see/a poem lovely as a tree….”) died July 30, months away from the end of the First World War, from a German’s sniper bullet in northern France.

Kilmer’s poetic star has faded over the past century, in part because his formalism fell out of style with the rise of modernism and especially “free verse,” in part because he was so very Catholic. In his day, he was compared to an American Belloc or Chesterton.

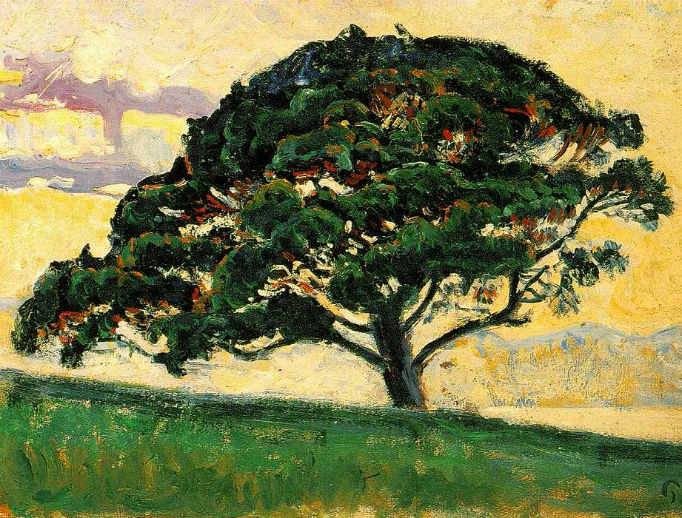

“Trees” is a poem full of spiritual allusions. It draws its sustenance from the earth (“A tree whose hungry mouth is pressed/against the earth’s sweet flowing breast”) but sores up (“looking to God all day”), raising its branches like arms “to pray.”

That is like us: standing firmly on the earth, but drawn up to heaven. The tree’s line, lifting the eyes up, reminds us of the same thing that Gothic cathedral architecture tried to do: raise human eyes upwards, heavenwards, God-wards.

In a clear parallel to this Sunday Gospel, Kilmer speaks of the “nest of robins” found in the tree, perhaps with some allusion to the old Irish legend that the robin’s breast is red because it was stained on Calvary. Kilmer speaks of the tree “upon whose bosom snow has lain//who intimately lives with rain.” Snow, in the Bible, is a sign of purity (Psalm 51:7); rain is often a symbol for the sufferings and sacrifices we all have to bear.

We are supposed to be trees, standing on this earth but drawn to God, wanting to go beyond this world but still a part of it. The Bible speaks about God expecting us to produce good fruit and warning about failing to produce that yield “at the proper time.” One of those fruits is our availability for our fellow creatures, most especially our fellow human beings: both Mark and Kilmer speak of that when they talk about the “birds of the air” that find shelter in the tree’s branches. Finally, the tree’s good fruit is its beauty: being what it should be, just like us, is God’s glory. St. Irenaeus of Lyons said it almost two thousand years ago: “The glory of God is man fully alive.”

And that life leads others to God. Just as the discerning eye recognizes the proximity of summer when the fig tree blooms, others recognize that the miracle and contingency of life itself points to something beyond. Avery Dulles, the son of the American Secretary of State, was raised Presbyterian but becoming increasingly agnostic when he began his undergraduate studies at Harvard. His own conversion—to faith, to Catholicism, to becoming a Jesuit (and eventually being named a theologian cardinal)—began when he spied a tree beginning to blossom on the Charles. Thereafter, he never doubted God’s existence or goodness. The tree didn’t have to be, much less be in bloom. But, in its humble corner in Harvard Yard, doing what it should be doing, giving forth life, its “prayer” pointed another to God.

Joyce Kilmer loved Ireland very much: his poem “Easter Week” honored the 1916 Rising, and his “Apology” honored Joseph Plunkett. His essay, “Holy Ireland,” honors a theme like Kilmer somewhat less in contemporary vogue: Eire’s Catholic heritage. But, on the Eleventh Sunday of Ordinary Time, almost a hundred years after he died at Seringes-et-Nesles, we might remember that “only God can make a tree.”