Humanae Vitae is All About Communion

The proper understanding of the body is essential to understanding the person

Last week’s Gospel and my reflection last week both focused on earthly food: Jesus multiplied loaves and fishes to feed the crowd, and I discussed how the specter of “overpopulation” fueled opposition to Humanae vitae—paradoxically most powerfully in countries and societies least threatened by hunger.

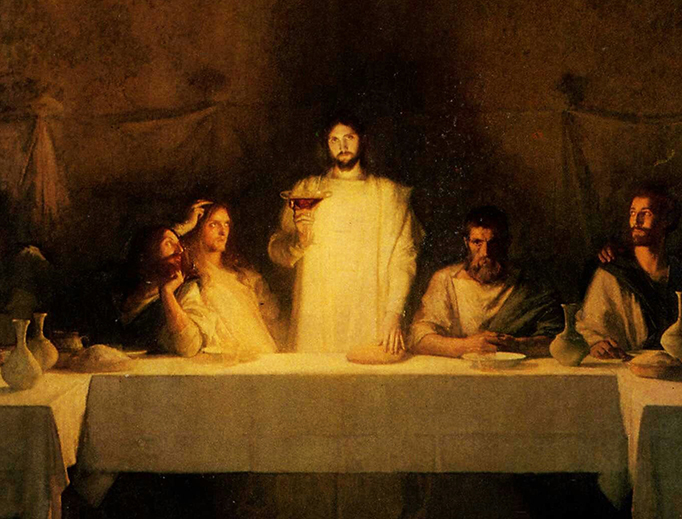

But these five weeks of Gospel readings on the Eucharist are taken from John 6 and, in John, Jesus’ individual deeds are “signs” of a deeper reality. Jesus’ multiplication of the loaves is not just his version of a first century Band Aid effort to “feed the world.” It is the jumping-off point for his teaching about the “food that endures.” Feeding the crowds is Jesus’ segue to teaching about Communion.

Likewise, I intend a segue on Humanae vitae beyond the Malthusian fears of population outstripping food supply. Humanae vitae is an opportunity to discuss a Communion of Persons (communion personarum).

Come to think about it, that’s also what the Eucharist is: a communion of persons.

The notion of “communion of persons” is very prominent in Karol Wojtyła’s writings on sexual ethics. The most powerful argument he marshals for Catholic sexual ethics is the value of the person: the person is a being with whom the only appropriate relationship is one of love, not of use.

But we must understand – and love – the “person” completely. We need an “integral vision of the person,” not a “partial perspective.”

The human person is body and soul. The body and its functions are not something lesser than or outside the “person.” The body and its functions are the person, as much as his soul. Anybody who doubts that is a dualist gnostic, not a Christian. We say, after all, every Sunday: “I look forward to the resurrection of the body,” not “I look forward to my soul’s life everlasting in the life of the world to come.” Your body will be part of that life. You — body and soul, as one human entity, did good or evil. You — body and soul, as one human entity, will enjoy eternal bliss or damnation based on those deeds.

I make this point because there is a very strong undercurrent in modern thinking that devalues the body. Perhaps it does not treat it as disparagingly as the ancients did, calling the body a “prison” of the soul,” but the result is just as negative: ever since Rene Descartes, the Western mind has treated the body and what happens in the body as sub-personal. For Descartes, “I” is a thinker with a body attached; for genuine Christianity, “I” am a body and soul composite whose distinguishing feature is that I can think. But that thinking does not negate my bodiliness.

Just consider how modern thinking deprecates the body. When person in a coma is no longer just seriously ill, but he often becomes a “vegetable.” Handicaps are deemed justification for elimination, especially before birth. Parenthood has increasingly less and less to do with the body and is becoming more and more a state of mind: not only do we parcel it into genetic, gestational and social components, but we even let the last one trump everything else: “What makes a parent is love.” Finally, in the contemporary debate over “gender,” the reality of the body is again canceled out: sexual differentiation, which permeates a person down to his chromosomes, is now a state of mind, “fifty shades of gender.”

So, before we are going to talk about a communion of persons, we have to know what a “person” is. A human person has a human nature, which is normative and which was created by a God who is good.

This leads us back to the body and the person. When a person is fertile, i.e., he or she is capable of becoming a parent, that capacity is not something sub-personal. It is not something beneath the “person” (i.e., consciousness) to be manipulated at will, but it is an aspect of the person.

Which leads us back to the problem of a communion of persons. If, as Karol Wojtyła rightly insists, a person is to be loved and not used, then to love a person is to love a person in the entirety of who he is as a person. To reject the beloved’s fertility is to say: “I love how you make me feel,’ I’m in love with your body,’ but I do not love you as a person who can share life. That dimension of you as a person has to be remade.” That is not love; that is use.

Like in John’s Gospel, where the feeding of the crowds is a “sign,” so, too, is the body a “sign” of the person. As the Jesuit Paul Quay once pointed out, the meaning of the body is not elastic, flexible of interpretation however you want.

Consider this example. If I pull back and give you a powerful right hook in the face so as to bloody your nose, you are probably going to ask: “why did you hit me?” and not “why did you hit my body?” But unless the body is you, the former is inaccurate. (It would also then render assault no longer a crime against the person but, rather, a form of vandalism). And if I told you, “I whacked you because I love you,” you would—rightly—consider me crazy because giving somebody a bloody nose cannot be understood as an act of love, no matter how consciously convinced the person claiming it is.

Which simply means: the body is (along with the soul) the person. Whatsoever you do to my body, you do unto me.

That’s why the Eucharist is the “body of Christ,” not (pace most Protestant Eucharistic theologies) a memory of Jesus. That is why we affirm that, in receiving the Eucharist, we offer “the body and blood, soul and divinity of Our Lord Jesus Christ,” i.e., the whole Person.

The proper understanding of the body is essential to understanding the person, which is prerequisite to understanding how persons relate together in communion, be it the communion of persons of the spouses or the communion of persons of spouses who are parents and their children. We will consider both of these understandings of person and communion over the next two weeks, even as the Lord expands on His Teaching about Communion in the Sunday Gospels.

And one last thought: this week includes the Feast of the Transfiguration, where Jesus is changed before His disciples. He is different, but it is clearly His body that Peter, James and John see. It is that same body they will seem in transfiguration at Easter. It is Mary’s same transfigured body we will honor assumed into heaven in about 10 days. And it is that same body that will be transfigured on the Last Day – transfigured by the “food that endures for eternal life.”