What Happens in Krakow, Doesn’t Stay in Krakow

World Youth Day and the Nature of Quest

Most of us have heard the phrase, “What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas.” The idea being, of course, that when you visit sin city, the effects stay there and you can return to your life without tarnish or rumor following you home. Sadly, sin is never private, never isolated, and only left behind by the grace of confession and penance.

The saints of Krakow—among them, St. Stanislaw, St. Jadwiga, St. Faustina, St. Maximilian Kolbe and St. John Paul IIdid not see life as just one day following another, but saw themselves as part of a larger divinely-inspired drama. They knew that God had a mission suited just to them. It was this mission that gave their lives meaning. But it went well beyond them. Their goodness, planted and nourished in Krakow, radiated throughout the whole world.

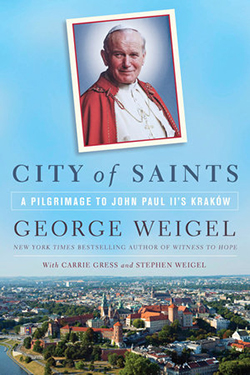

As George Weigel wrote about Wojtyla in our book, City of Saints:

Wojtyla’s biblical faith taught him something more about the dramatic character of the human condition: it taught him that each of our personal dramas “plays” within a cosmic and historical drama, the drama of salvation history. And that drama has God as producer, director, scriptwriter – and, ultimately, protagonist, for God himself enters the drama fully, in the person of his Son, so that the drama of history might be redirected to its proper trajectory, which leads from the creation to the Wedding Feast of the Lamb. Thus we do not live our personal dramas by ourselves. We are, as the Letter to the Hebrews teaches, surrounded by a “great cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12:1), who, alongside us and before us and ahead of us, are living, or have lived, the drama of their lives with in the great drama of salvation history. (City of Saints, 120-21)

Wojtyla saw his life as something bigger than just a cog in a machine. He saw it as an adventure, as a quest to discover and live God’s will in the face of raw evil.

But just what is a quest? A quest is timeless desire built into our souls. Think of the ancient, pre-Christian example in the Epic of Gilgamesh, or the sixteenth-century tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. The great twentieth century quest, The Lord of the Rings is the latest in the illustrious series.

In his book After Virtue, philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre taps into this desire of every human heart to see life as a quest. He explains the characteristics of a quest. First, in order for a quest to exist, one must have an idea of a good to be achieved. The epic tale of The Lord of the Rings would have been very short, indeed, if Frodo Baggins, rather than risking everything to save civilization, had decided that he didn’t want the bother of returning the ring but chose instead to rest comfortably in his Shire life. Poland’s saints, like all saints, are quest seekers whose goal is heaven and whose path is service to Christ and his Church.

Second, the notion of quest is not to search for something specific, like geologists for oil or miners for gold. It is much more vague, requiring a type of trust as events unfold. The unexpected, unfolding events along the way, and not just the final goal, are an essential characteristic of a quest. As MacIntyre explains: "It is in the course of the quest and only through encountering and coping with the various particular harms, dangers, temptations and distractions which provide any quest with its episodes and incidents that the goal of the quest is finally to be understood.” A quest requires that one learn through it both what one is seeking – mission and vocation – while also gaining self-knowledge and character.

Third, a quest usually involves traveling to some place foreign and unfamiliar to provide a new way of looking at things one already knew, or to discover something new. Embarking on a pilgrimage to Krakow certainly constitutes the right elements of foreign and unfamiliar, while offering the saints of the Church as both models and tour guides for the adventure.

It is in a quest that we are often surprised, both in ourselves, in our fellow travelers and in God. As Pope Francis made clear during the opening Mass at World Youth Day 2013 in Brazil, God "asks us to let ourselves be surprised by his love, to accept his surprises. Let us trust God.” Let us, indeed.

The world awaits the fruit of this pilgrimage and looks to the youth to see that “what happens in Krakow, doesn’t stay in Krakow.”