Countdown to WYD: Downton Abbey, Polish Style

Sadly, Downton Abbey came to an end this year after six seasons of intrigue, sorrow, and delight. If you watched the series, this scene will be familiar:

A buzz and a hum were everywhere. The musicians were gathering to blast a welcome to the returning hunters. In the great hall, preparations were made for the evening feast, wines were emerging from the cellars, there was a clinking of glass and silver, and everywhere the sounds of rushing feet and shouting commands.

Although this may appear to be the busy working of the downstairs staff preparing for another Crawley meal, this scene’s provenance is quite different. Welcome to the grandeur of the Polish aristocracy.

Although nowhere near the opulence of Downton’s Highclere Castle, Maleszow sounds grand enough. “As I have not seen many castles besides Maleszow,” Franciszka explains, “I cannot judge whether it is pretty or not. I only know that I like it very much. Some people think that our castle, with is four stories and its four bastions, surrounded with a moat full of water crossed by a drawbridge, and situated amidst forests in a rocky country, looks rather gloomy, but I do not think so at all.”

One of the most interesting tidbits is when the Countess describes a Polish custom before marriage. The intended bride is given a tangled skein of silk to wind. If she can do it, she shows she has enough patience to meet the trials of married life.

One very dramatic difference between Downton Abbey and the life of eighteenth century gentry is the overt piety. The diary makes clear that Catholicism played a significant role in their daily life -- including Mass, morning and evening prayers, the Angelus, and the typical Polish observance of holy days and seasons.

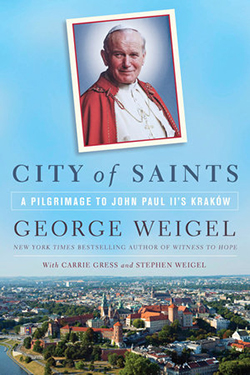

I discovered the Countess Franciszka in this historic gem, A Girl Who Would Be Queen, by Eric P. Kelly and Clara Hoffmanowa while researching City of Saints. Conceptually, the book is unique: it combines Kelly’s heavily researched historical fiction of the Countess’s life with Hoffmanowa’s adaptation of her actual diaries.

Tragically – and a bit hauntingly – the book was published in 1939, the last year the aristocracy held much sway in Polish politics as the Germans rolled in. The book notes that the diaries of the countess are available at Krasinski Library in Warsaw. After the start of the war the contents of that library were moved to the National Library. It is not clear if her remarkable papers were spared when the Nazis torched 85 percent of Warsaw, including most of the city’s libraries.

The book tells the story of how Franciszka married Charles of Saxony, the Duke of Courland who – as the son of King Augustus III of Poland – was the heir apparent. Their marriage, however, was kept secret because her noble birth was not high enough in the dynastic line.

The couple was exiled as a result of rivalries between powers inside and outside of Poland, and the country called Poland was erased from the map, being partitioned by the Russians, Prussians and Austrians. In exile, the countess was granted the title of princess, but a queen she would never be. (The crown that eluded her, however, was eventually won by her great-grandson, King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy.)

Her story and her thwarted role of queen highlight the tumultuous relationship between the country’s rulers and the expansive aristocracy that plagued Poland for centuries. Polish political history is both complex and perplexing. The gentry class made up somewhere between eight to ten percent of the population, while in other countries the make-up was closer to two to three. As I wrote in City of Saints:

This large and often unruly class of gentry, all of whom asserted a right to membership in the parliament, the Sejm (where matters had to be decided unanimously), was a significant check on royal power— and a considerable factor in governmental paralysis. Moreover, from the mid-sixteenth century on, the Polish monarch was elective, and kings were dependent throughout their reigns on the coalitions of gentry they had assembled to secure their election. Thus Polish history is rife with crises of authority, which too often coincided with foreign pressures and intrigues – all of which eventually resulted in the three partitions of Poland that took place in the eighteen century and the end of Polish independence in 1795. (City of Saints, 147)

Franciszka’s life also gives a unique look into the sacrifices made by Poles to fight the invading powers, where great families who had been battling each other for centuries came together to fight against their common Russian enemy, though sadly their confederacy ended in failure.

A look into the aristocracy of Poland, however, offers quite a different and more accurate picture of Poland than most of us have from what we know of the dark and tragic days of World War II, the gray oppression of the communists, or even the impoverished plight of Polish immigrants to American over the centuries. It becomes easier to imagine Warsaw being the “Paris of the East” as well as to believe that there was once vibrant life in the rural castle ruins that dot the countryside.

Aristocratic ruins

Historically, Poland can boast of many magnificent castles, including Krzyżtopór Castle, which was designed around the idea of the calendar: 365 windows, a chamber for each week, twelve great rooms for each month, and four towers, one for each season. Most castles, however, are in ruins, including Franciszka’s beloved Maleszowa. The Swedes, Russians, Prussians, Austrians, Germans and Soviets took turns destroying or neglecting the cultural icons of rural defense.

Recently, developers have moved in to help restore many of the castles to their former glory, as discussed in this Smithsonian article. One of the rebuilders of a medieval castles asked, “Why should the Germans have their castles on the Rhine, the French their castles on the Loire, why should the Czechs have so many castles open to the visitors and why should the Poles have only ruins?” Why, indeed.

Several Polish castles have been restored completely and are now being used as museums or hotels. The Polish Office of Tourism has a list of the Seven Most Beautiful Castles that might be worth adding to your travel itinerary.

* * * * * * *

One of the most dramatic restorations after the Second World War is the Castle of the Teutonic Order in Malbork. It is roughly an hour and half south east of Gdansk and on the route between Warsaw and Gdansk. Parts of the famed castle are visible from the train station.